HMAS Armidale (I)

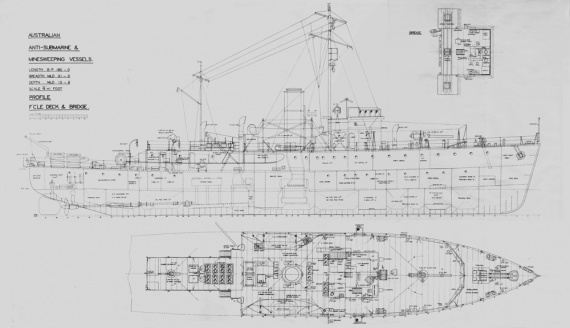

| Class |

Bathurst Class |

|---|---|

| Type |

Australian Minesweeper |

| Pennant |

J240 |

| Motto |

Stand Firm |

| Builder |

Mort’s Dock and Engineering Co Ltd, Sydney |

| Laid Down |

1 September 1941 |

| Launched |

24 January 1942 |

| Launched by |

Built in dock and not launched therefore no ceremony was held |

| Commissioned |

11 June 1942 |

| Decommissioned |

1 December 1942 |

| Fate |

Sunk by Japanese aircraft on 1 December 1942 |

| Dimensions & Displacement | |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 56.69 metres |

| Beam | 9.45 metres |

| Draught | 2.59 metres |

| Performance | |

| Speed | 15 knots |

| Complement | |

| Crew | 85 |

| Propulsion | |

| Machinery | Triple expansion, 2 shafts, 2,000 hp |

| Horsepower | 2000 |

| Armament | |

| Guns |

|

| Other Armament | Depth charge chutes and throwers |

| Awards | |

| Battle Honours | |

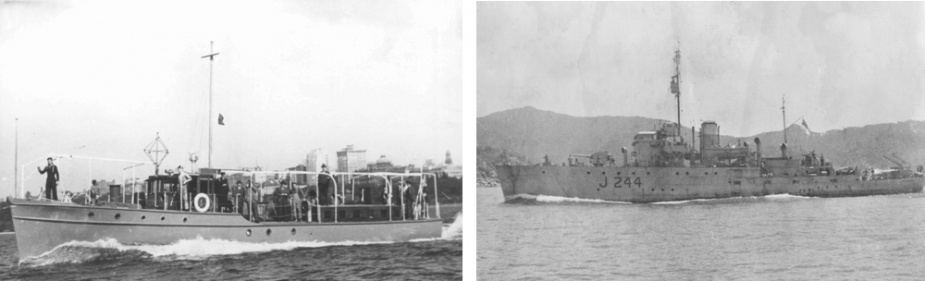

HMAS Armidale (I) was one of sixty Australian Minesweepers (commonly known as corvettes) built during World War II in Australian shipyards as part of the Commonwealth Government’s wartime shipbuilding programme. Twenty were built on Admiralty order but manned and commissioned by the Royal Australian Navy. Thirty six (including Armidale (I)) were built for the Royal Australian Navy and four for the Royal Indian Navy.

These ships established an enviable reputation in the RAN as ‘maids of all work’ but were also renowned for ‘rolling on wet grass’ by those who served in them.

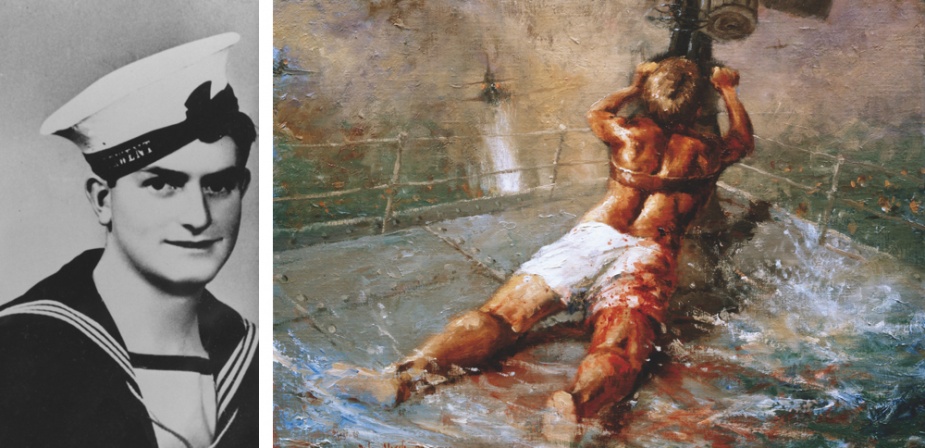

Armidale (I) commissioned at Sydney on 11 June 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Commander David H Richards RANR(S).

Following a workup period Armidale (I) was brought into operational service as an escort vessel protecting convoys operating between Australia and New Guinea. That service ended in October 1942 when she was ordered to join the 24th Minesweeping Flotilla at Darwin. Armidale arrived at Darwin on 7 November 1942.

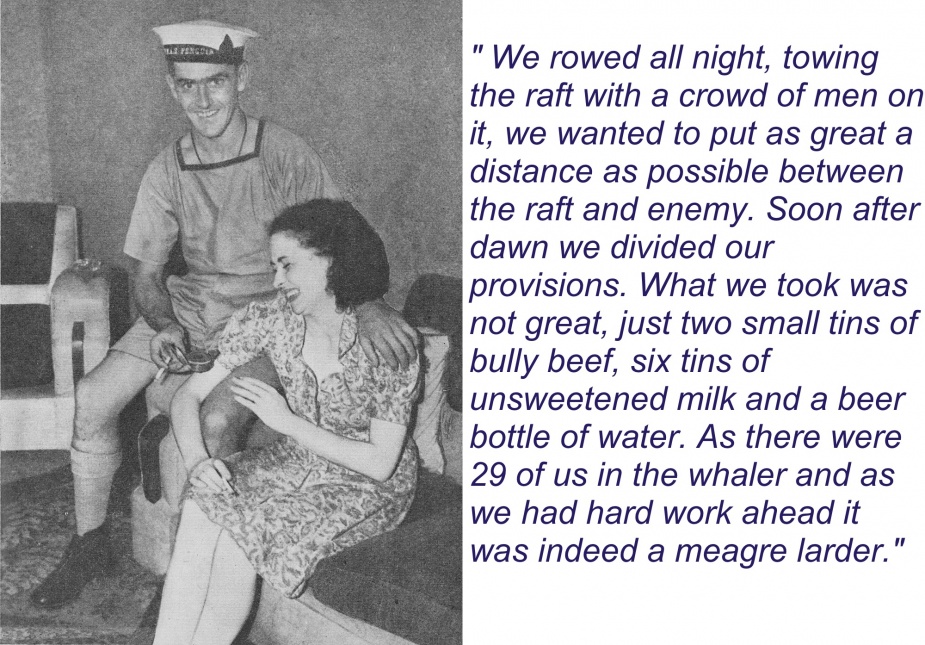

On 24 November 1942 Allied Land Forces Headquarters approved the relief/reinforcement of the Australian 2/2nd Independent Company which at that time was holding out in Japanese occupied Timor.

The withdrawal of 150 Portuguese civilians was also approved and consequently plans were made in Darwin for HMA Ships Castlemaine (Lieutenant Commander Philip J Sullivan, RANR(S)), Armidale and Kuru (Lieutenant JA Grant, RANR), a shallow draught, 76 foot wooden motor vessel, to effect the relief operation which was code named Operation HAMBURGER.