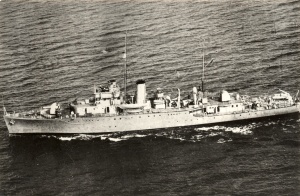

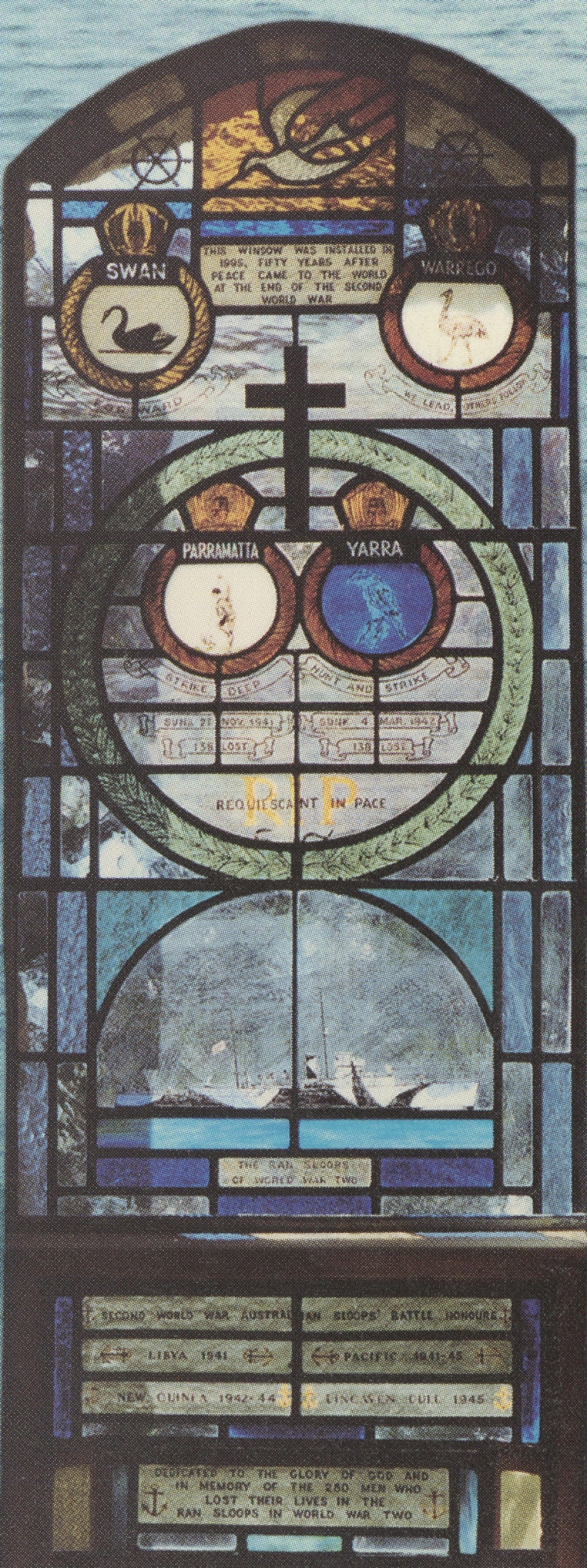

HMAS Parramatta (II)

| Class |

Grimsby Class |

|---|---|

| Type |

Sloop |

| Pennant |

U44 |

| Builder |

Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Co Ltd, Sydney |

| Laid Down |

9 November 1938 |

| Launched |

10 June 1939 |

| Launched by |

Mrs Evora Francis Street, wife of the Minister for Defence |

| Commissioned |

8 April 1940 |

| Decommissioned |

27 November 1941 |

| Fate |

Lost in action on 27 November 1941 |

| Dimensions & Displacement | |

| Displacement | 1060 tons |

| Length | 266 feet |

| Beam | 36 feet |

| Performance | |

| Speed | 16.5 knots |

| Armament | |

| Guns |

|

| Awards | |

| Inherited Battle Honours | |

| Battle Honours | LIBYA 1940-41 |

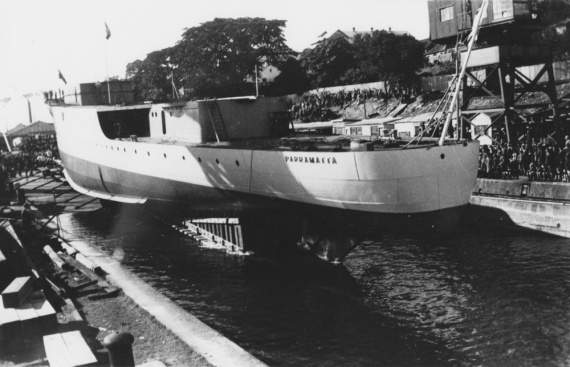

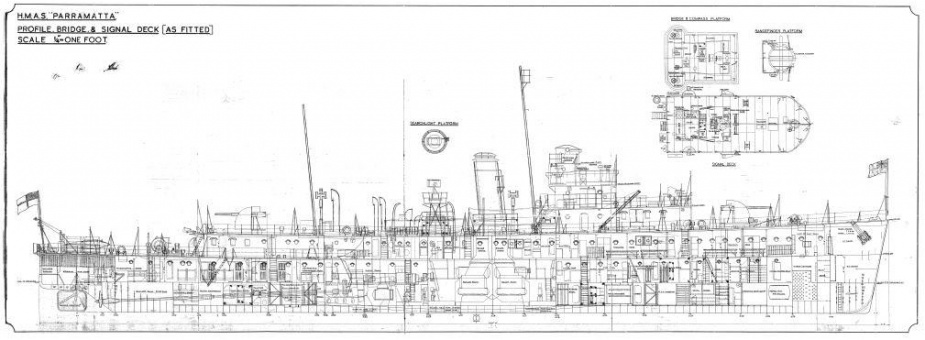

The RAN’s second Parramatta was laid down at Cockatoo Island Dockyard, Sydney on 9 November 1938. The Grimsby Class sloop was launched by Mrs Evora Francis Street, the wife of the Federal Minister for Defence on 10 June, 1939. As the slip was required by another hull, Parramatta was unusually launched prior to her engines being installed.

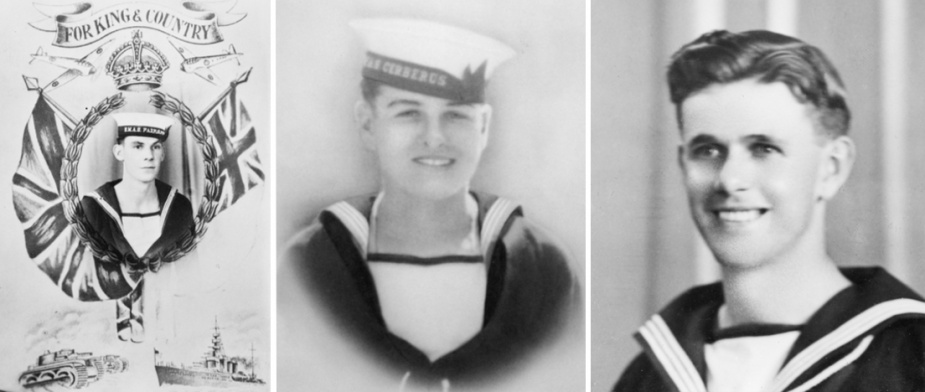

HMAS Parramatta commissioned at Sydney on 8 April 1940 under the command of Lieutenant Commander Jefferson H Walker MVO, RAN, a 39 year old officer who had entered the Royal Australian Naval College in 1915 at the age of 13½ years. She was his first command.

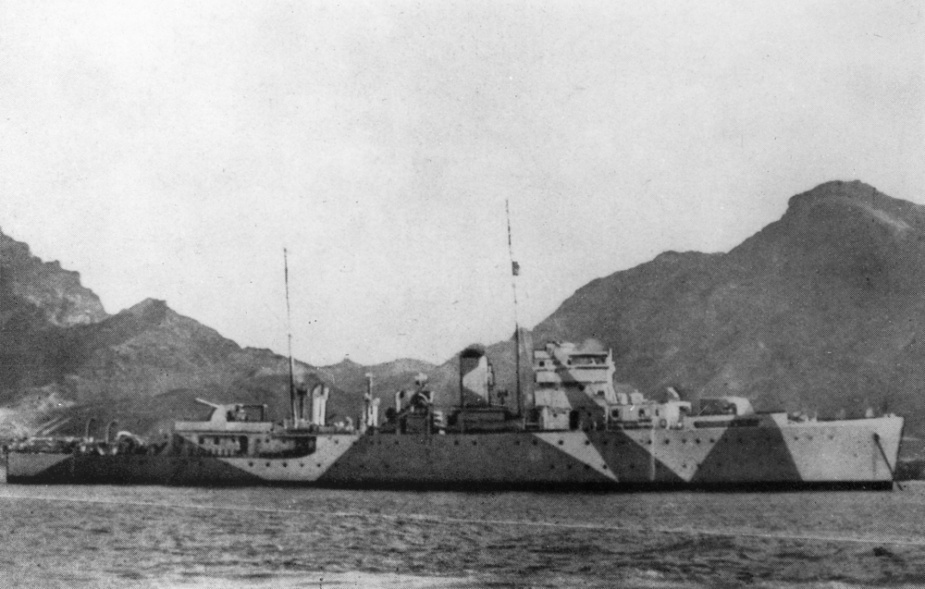

Following a brief period exercising with the 20th Minesweeping Flotilla, Parramatta sailed from Fremantle on 29 June 1940 en route to the Red Sea where she reported for duty to the Senior Officer, Red Sea Force, at the end of July. Except for a visit to Bombay in December 1940, Parramatta spent the next nine months in one of the world’s most torrid zones escorting, patrolling and minesweeping. It was monotonous work in the worst possible conditions relieved only by occasional futile Italian air attacks against the convoys under escort.

In April 1941 she took part in the British operations against Italian Eritrea, East Africa. One of her last tasks as a unit of the Red Sea Force was towing the cruiser HMS Capetown from Eritrea to Port Sudan after she had been torpedoed by an Italian ‘E’ Boat during the night of 7/8 April 1941.

In May 1941 Parramatta transferred to the control of the Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Station, beginning with three weeks based on Port Tewfik at the head of the Gulf of Suez. On 3 June she reached Alexandria where Walker commented that at last after “months of monotony in the Red Sea” he was pleased that his “rather young and developing Ship’s company” would be stimulated by contact with the battle scarred Mediterranean Fleet. Soon afterwards Parramatta was assigned to duty on escort in support of the campaign in Libya (Western Desert). She sailed from Alexandria on her first run to the battle area on 15 June carrying a Naval Port Party to Mersa Matruh.

After dark on 22 June 1941 Parramatta left Alexandria on her first run to beleaguered Tobruk, escorting in company with the sloop HMS Auckland, the small steamer Pass Of Balmaha carrying a cargo of badly need petrol. The warships were to leave her off Tobruk and wait to seaward while she discharged her cargo and then escort her back to Alexandria.

Steaming close inshore to gain the benefit of fighter protection from the land, the ships made slow but steady progress. For 36 hours there was no sign of the enemy but at 8:40am on the second day out a single reconnaissance plane was sighted high up a few miles westward. Half an hour later the first of three fruitless attacks developed, the last from a single aircraft at 1:45pm. Then at 5:30pm Parramatta received a warning from Auckland and Walker, scanning the sky, sighted three formations each of 16 dive bombers manoeuvring to attack.

As they worked round in order to dive straight out of the blazing westerly sun both ships opened the heaviest barrage they could muster. Then they came in, diving in twos and threes. Tall fountains of water rising from the sea marked near miss after near miss. Auckland was hit in the stern and disappeared from view in a cloud of thick brown smoke. She emerged out of control, guns still firing, and heading straight for Parramatta who had to swing away to avoid a collision. “As she passed”, wrote Walker, “I saw that she was an utter wreck abaft the mainmast, with no stern visible.” After fifteen minutes the last of the bombers was droning eastwards. Miraculously both Parramatta and the petrol carrier had escaped damage. Auckland, stopped and listing heavily to port, began to abandon ship and Walker closed her to begin the work of rescuing her crew. She was barely cleared when a heavy internal explosion lifted the stricken ship “slowly and steadily about six or seven feet into the air. Her back broke with a pronounced fold down the starboard side.” Slowly, as if reluctant to go, she rolled quietly over and sank.

At 6:30pm the enemy returned, machine gunning Auckland’s survivors as they drifted in boats and skiffs, on rafts and some still afloat in their lifebelts. Parramatta was forced to withdraw to gain sea room until darkness fell. For two hours the bombers kept coming so that according to Walker “there seemed always one formation falling about like leaves in the zenith and then diving in succession, one moving forward into position and one splitting off and coming in at 45 degrees.” But at last after the enemy had done his futile worst and failed to sink either Parramatta or her charge the attacks ceased “as the sun’s lower limb touched the horizon at 8:25pm.” In the deepening dusk of the Mediterranean night Walker turned his ship towards the scene of Auckland’s loss. There she was joined by the Australian destroyers HMA Ships Waterhen (I) and Vendetta (I). While the destroyers circled her she picked up 164 survivors before setting out for Alexandria. Pass Of Balmaha, damaged in the bunkers, was taken in tow by Waterhen (I) to Tobruk with Vendetta (I) as escort.

After cleaning ship and making good minor damage, Parramatta resumed escort duty to Tobruk. En route to Mersa Matruh on 27 June she was attacked by a submarine. Fortunately, however, although the enemy’s aim was good his torpedo ran too deep and passed harmlessly underneath the ship. From Mersa Matruh the Australian sloop picked up the Pass Of Balmaha off Tobruk and on 30 June again entered Alexandria Harbour where she remained making good defects until 18 July. Thereafter until the end of the month she operated as one of the escort vessels covering the reinforcement of the British forces in Cyprus.