HMAS Sydney (II)

| Class |

Modified Leander Class |

|---|---|

| Type |

Light Cruiser |

| Pennant |

D48 |

| Builder |

Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson Ltd, Wallsend on Tyne, England |

| Laid Down |

8 July 1933 |

| Launched |

22 September 1934 |

| Commissioned |

24 September 1935 |

| Fate |

Sunk in action on 19 November 1941 |

| Dimensions & Displacement | |

| Displacement | 7250 tons standard |

| Length | 555 feet overall |

| Beam | 56 feet 8 inches |

| Performance | |

| Speed | 32.5 knots |

| Complement | |

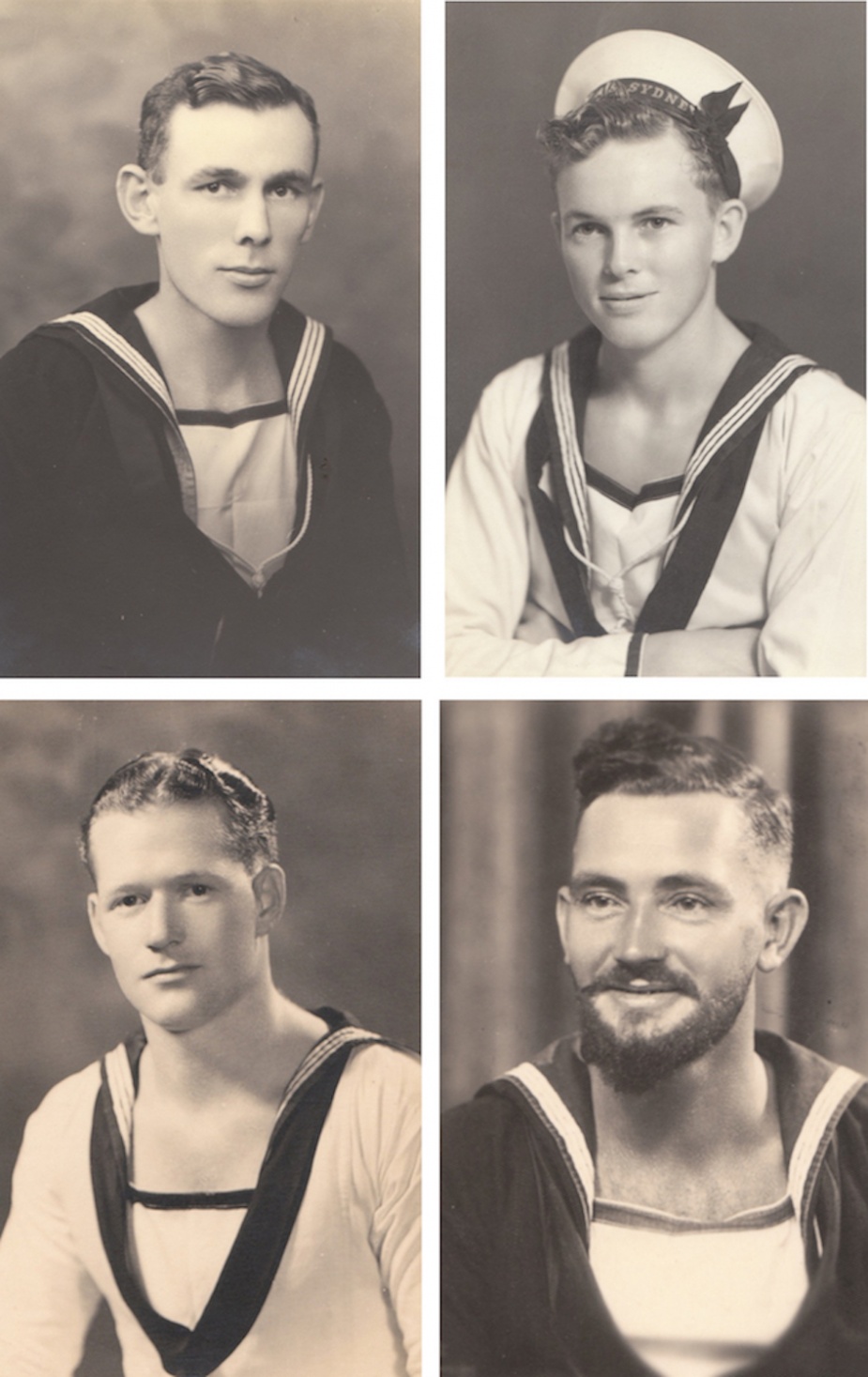

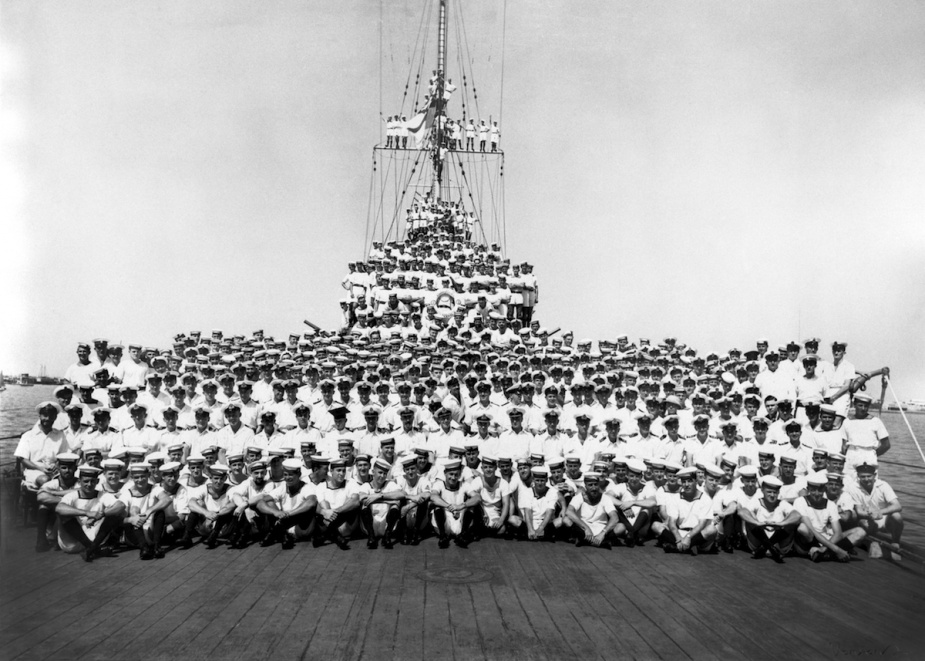

| Crew | 645 |

| Propulsion | |

| Horsepower | 72,000 |

| Armament | |

| Guns |

|

| Torpedoes | 8 x 21 inch torpedo tubes ( in 2 quadruple mounts) |

| Awards | |

| Inherited Battle Honours | |

| Battle Honours | |

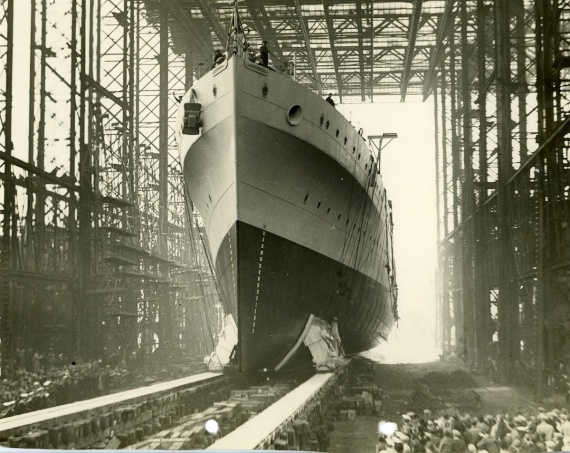

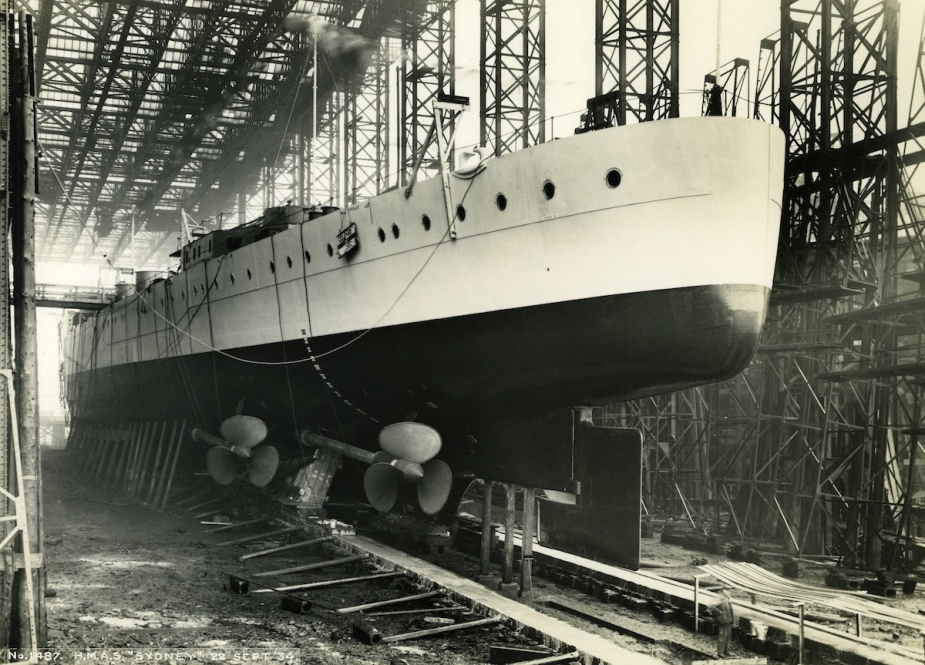

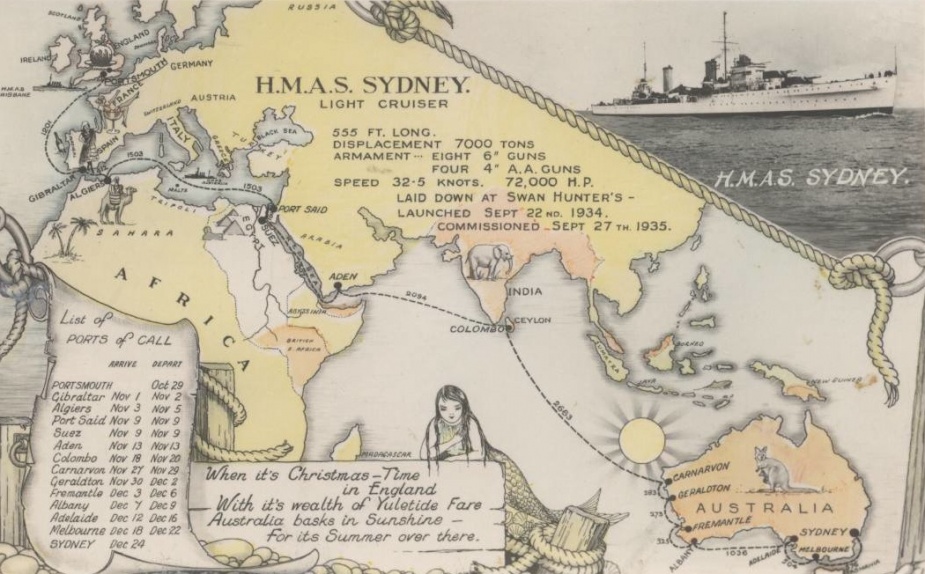

On 8 July 1933 the ship that would become Sydney (II) was laid down as HMS Phaeton in the shipyard of Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson, at Wallsend-on-Tyne in England. The following year she was purchased, in build, by the Australian Government and renamed Sydney, in memory of her namesake and the capital city of New South Wales. She was launched on 22 September 1934 by Mrs Ethel Bruce, the wife of Mr Stanley Bruce, MC, the Australian High Commissioner to Great Britain and former Australian Prime Minister.

Sydney was one of three British modified Leander Class light cruisers acquired by the RAN in the years immediately preceding World War II. Her sister ships were Perth and Hobart and in Australia they were known as Perth Class light cruisers.

In January 1935, Commander JA Collins, RAN, arrived at Wallsend-on-Tyne to take up the appointment of Executive Officer in Sydney. Collins, a Gunnery Officer, was a graduate of the inaugural entry of the Royal Australian Naval College and although he did not know it at the time, it would be under his leadership that Sydney would later reach the pinnacle of her career during the hard-fought Mediterranean campaign of World War II, which was then just four years distant.

Sydney was completed on 24 September 1935 and following acceptance trials she commissioned under the command of Captain JUP FitzGerald, RN. With a steaming party embarked, she then made the short voyage to Portsmouth where the balance of her Australian ship’s company was waiting to join her. These men had been standing by in Portsmouth having sailed there in the obsolete light cruiser HMAS Brisbane which was being paid off for disposal.

The crew of Sydney liked what they saw before them. As her longest surviving officer, Lieutenant Commander John Ross, was to recall in his memoirs:

It was an exciting and proud moment for us as we watched this brand new ship - the last word in cruiser design - come gliding in, her new paintwork shining and her deck snow-white in the morning sunlight.

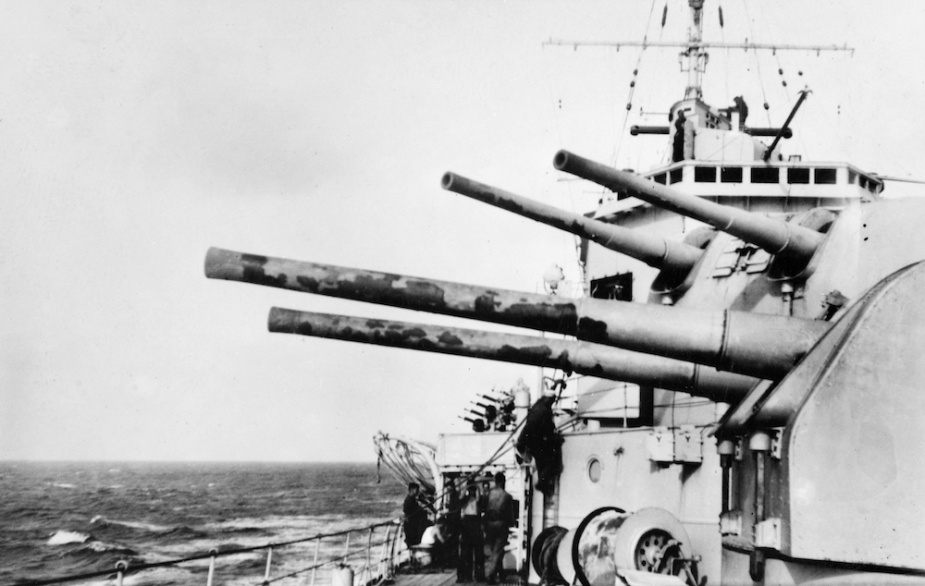

Sydney was undeniably a modern, handsome looking ship with sleek businesslike lines. With an overall length of 555 feet, a beam of 56 feet 8 inches and a standard displacement of 7250 tons she was much larger than her predecessor. Her main armament consisted of eight 6-inch Mk XXIII guns, housed in four Mark XXI twin turrets. The two forward turrets were designated 'A' and 'B' respectively, while the two after turrets were designated ‘X’ and ‘Y’.

Her secondary armament comprised four, 4-inch quick firing Mark V anti-aircraft guns and she was also equipped with eight 21-inch above-water torpedo tubes arranged in quadruple mountings. These mountings, when loaded, accommodated Mark IX torpedoes, each of which carried a 750-lb warhead. Her close range weapons included twelve 0.5-inch Vickers machine guns, sited on three Mk II quadruple mountings.

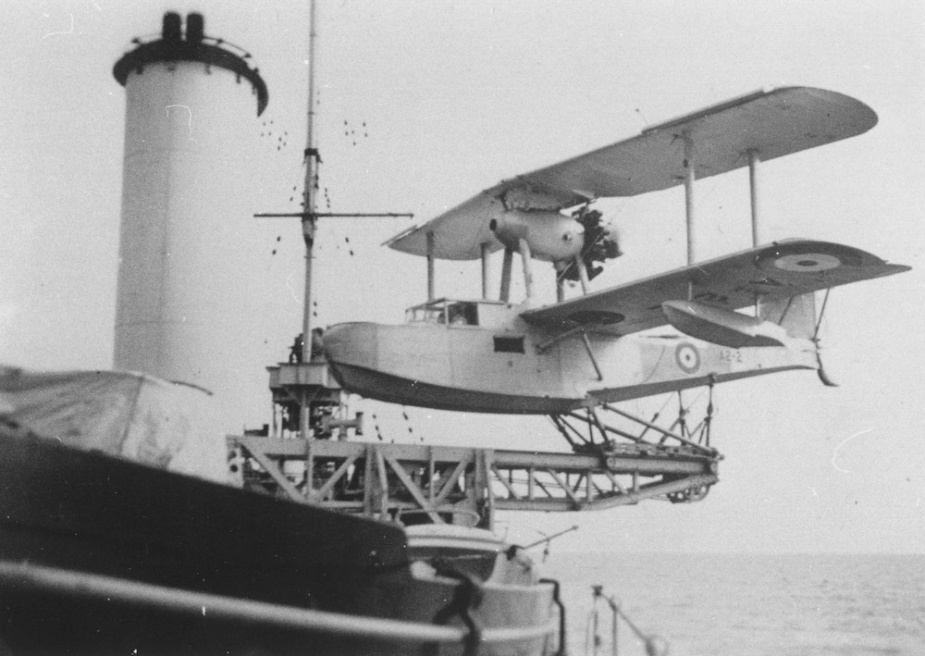

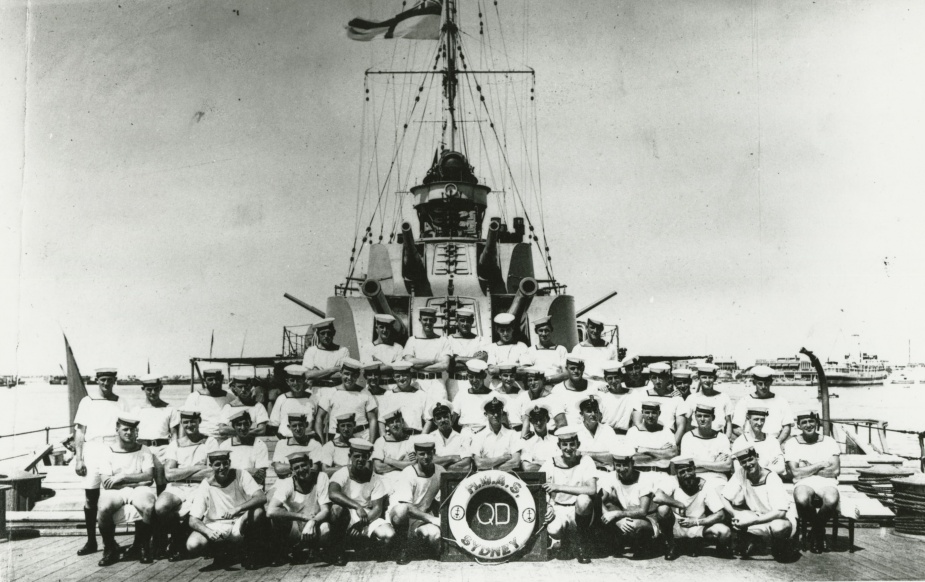

Sydney had a peacetime complement of 510 men that included six members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) who maintained and operated her amphibian, catapult launched aircraft. She also carried four civilian canteen staff.

With her commissioning crew embarked, Sydney spent the next month working-up in cold and blustery weather. At the end of that period Sydney's band led a contingent of men on a march through London to the famous Guildhall. There, the Lord Mayor of London hosted a farewell luncheon for the Australian sailors before they returned by train to Portsmouth to make preparations for Sydney's voyage to Australia.

On 29 October, Sydney steamed out of Portsmouth with her crew's spirits high. World events, however, were to soon impact on the newly commissioned warship when Italy invaded Abyssinia. Sanctions were quickly imposed on Italy and Sydney’s voyage home was interrupted when she received orders to proceed to Gibraltar to reinforce the Royal Navy’s Second Cruiser Squadron. The time spent working with the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean served her well and she continued to work up and hone her war-fighting skills. An unfortunate outbreak of rubella among her crew, followed by mumps, added to the crew's frustrations when the ship was placed under a quarantine order which prevented her crew from going ashore until the illness passed.

In March 1936 Sydney joined the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia in Alexandria as part of the First Cruiser Squadron. During the next four months the two Australian vessels continued to participate in numerous fleet exercises before finally sailing for home on 14 July.

Sydney's first Australian port of call was Fremantle, Western Australia. There she was warmly received by over 800 well-wishers, many of whom had fond memories of her namesake’s last visit to Fremantle in May 1927. Stopping only for a day, she was soon steaming east, bound for Melbourne, Victoria where she arrived on 8 August. The citizens of Melbourne turned out in droves to see the RAN’s new light cruiser and the ship received some 18,000 visitors when she was opened for inspection at Princes Pier.

On 11 August, Sydney made her long awaited entry through Sydney Heads and into Port Jackson where her arrival was viewed from the shore by thousands of citizens who had turned out to see her. As she slowly made her way through the channel she was saluted with the sound of ferry whistles as she made her way to a buoy off Garden Island. Once again the citizens of the city of Sydney had a ship that they could call their own and Australia’s overt adulation for the new cruiser soon became an extension of the affection and esteem held for HMAS Sydney (I).

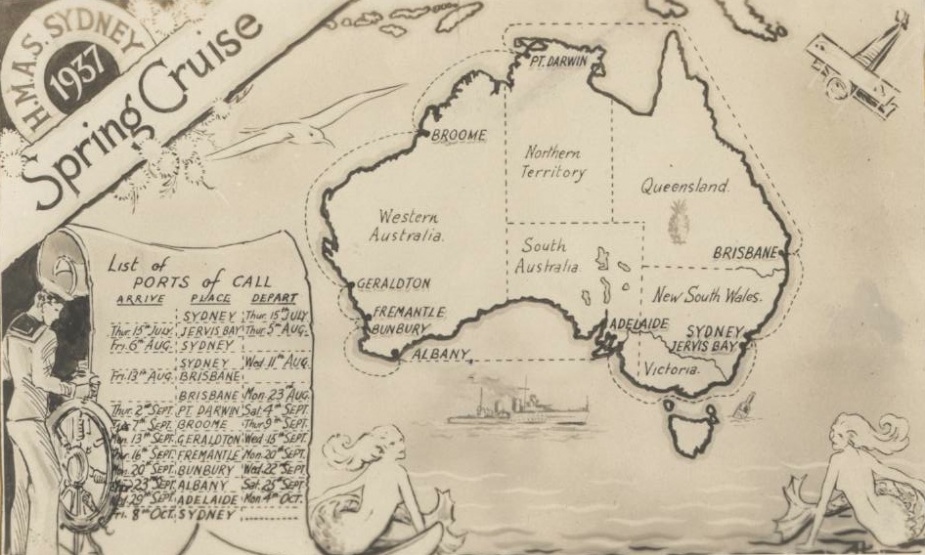

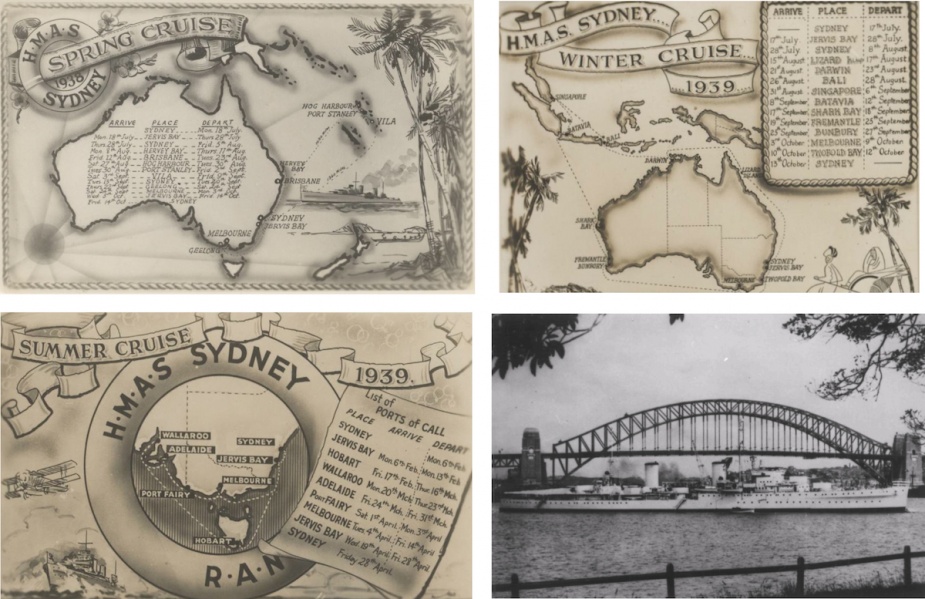

On 9 October 1937 Captain JWA Waller, RN, succeeded Captain Fitzgerald as Sydney's Commanding Officer. By that time Commander Collins had also been relieved, having spent almost three years as her Executive Officer. Between 1937 and the outbreak of war, Sydney was kept busy exercising, mostly on the Australian Station undertaking the usual round of seasonal training cruises.

Signs of a forthcoming war were apparent and it was with increasing apprehension that Australians watched Germany's and Italy's threats to peace in Europe steadily materialise. The Munich crisis of 1938 saw the partial mobilisation of Australia's naval forces; however, they were later stood down when it appeared that war had been averted.

In August 1939 it became apparent that the situation in Europe had again deteriorated and on 30 August the Commonwealth Government reaffirmed that it would place the ships of the RAN and its personnel at the disposal of the United Kingdom Government in the event of war. It did, however, find it necessary to stipulate that no ships (other than HMAS Perth) should be taken from Australian waters without prior concurrence of the Australian Government.

When the declaration of war came on 3 September 1939, Sydney had already taken up her war station at Fremantle. There she received a draft of an additional 135 ratings from the Fremantle Division of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve (RANR) and several additional officers to boost her complement to a war footing of 645 men. The cruiser then commenced a rigorous series of gunnery and torpedo exercises off the Western Australian coast and began patrol and escort duties.

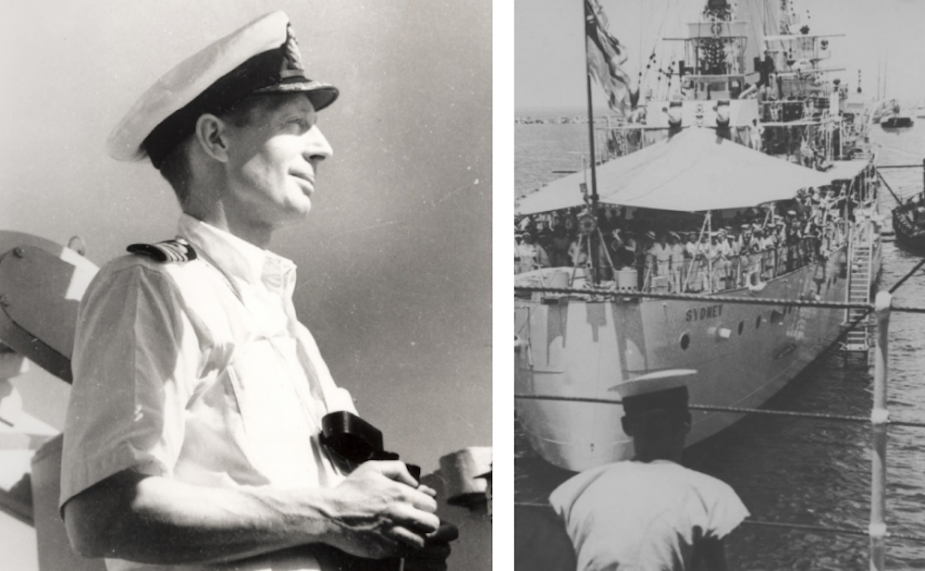

On 16 November, Captain JA Collins, RAN returned to Sydney to relieve Captain Waller, RN as her Commanding Officer. With three years experience under his belt as Sydney's Executive Officer, Collins selection as the first Australian officer to command the vessel was seen as a logical choice and one which was popular among many of the cruisers 'old hands', who were pleased to see him return.

Patrol work in the Indian Ocean continued for the remainder of 1939 before the cruiser was ordered to return to Sydney for docking and Christmas leave. Work ups followed early in the New Year and on completion, Sydney returned to Western Australia where she arrived on 8 February 1940. For the next few months she continued the familiar pattern of patrol and escort work that stretched from Bunbury in the south, to Carnarvon in the north. She also conducted patrols deep into the Indian Ocean. Throughout that time she became a familiar sight to the residents of Fremantle and Perth who, with many of their own kith and kin serving in her, had all but adopted the ship as their own.

On 1 May, Sydney was returning to Fremantle from escort duties when she received orders to proceed to Columbo at best speed. These orders were the instrument that would see Sydney leave the Australian Station and later win fame in the Mediterranean Sea. Taking passage via Singapore to refuel, Sydney arrived in Columbo on 8 May. Her time there, however, was short lived and she was soon directed to proceed to Alexandria, Egypt, where she joined the Royal Navy Mediterranean Fleet on 26 May.

The Mediterranean

In early June 1940, Sydney participated in a series of exercises as part of the Seventh Cruiser Squadron and it did not take her long to establish a reputation as an efficient and happy ship. On 10 June, with France about to fall and with Britain's future looking precarious, Italy entered the war on the side of Germany. It was now clear to the men of Sydney that the balance of power in the Mediterranean could easily shift and that the struggle for control of the sea there, was about to begin in earnest.

Within hours of Italy’s war declaration, the British Fleet, under the command of Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, RN, sailed on its first patrol sweep in the early hours of 11 June. Hostilities commenced almost immediately and first blood was drawn that night at 23:30 when the destroyer HMS Decoy reported sighting a submarine on the surface which she attacked. At dawn the next morning an oil slick two miles long was detected, although it was not known whether the submarine was destroyed. The enemy also struck quickly, when on 12 June the cruiser HMS Calypso was torpedoed by a submarine off Crete and sank with the loss of one officer and 38 ratings.

The Fleet completed its patrol sweep and returned to Alexandria two days later where it was forced to make a cautious entry due to the presence of minefields which had been laid by enemy submarines off the harbour entrance. The war in the Mediterranean had erupted swiftly and for the young Australian sailors in Sydney it was a sobering introduction to war at sea in the northern hemisphere.

On 22 June, France signed an armistice with Germany, the terms of which called for French Naval units deployed abroad to return to France where they would be demobilized under the supervision of the Axis forces. As feared, the balance of sea power had indeed shifted and the British Government resolved that under no circumstances should the French Fleet be permitted to fall into the hands of the enemy. It was a matter which was eventually settled by extreme measures on one hand, and considered diplomacy on the other.

In the Western Mediterranean the majority of the French fleet was in the port of Mers-el-Kebir at Oran. There the French Admiral in command was given an ultimatum. He could order his ships to sail to Britain or to the United States where they would be interned; demilitarize them in situ, or face annihilation by units of the Royal Navy. Tragically, with no positive response forthcoming, the majority of the fleet was neutralized with force.

In Alexandria, where Sydney was berthed, the situation was similarly tense, with many French naval units present in the harbour and now under the guns of the Commonwealth warships. There, Admiral Cunningham insisted on negotiating with his French counterpart, Vice Admiral Godfroy, who up until the signing of the armistice had been operating alongside the Allied warships. Through his diplomacy tragedy was averted when Godfroy agreed to demilitarize his ships, keep them in port and reduce their crews to 30 percent. It was with great relief that Sydney's menacing guns were trained back to the more benign fore and aft position.

Throughout June Sydney participated in numerous patrols and also took part in a major shore bombardment of Bardia later in the month. During this bombardment Sydney's amphibian Seagull aircraft was launched to assist in coordinating the cruiser's fire. The combined RAAF/RAN aircrew who manned the aircraft had no sooner begun their task when they were set upon by fighters which seemed intent on shooting them down. They put up a spirited defence in the lumbering amphibian before the aggressors broke off their attack leaving the Seagull full of holes and barely airworthy. Her pilot, Flight Lieutenant TM Price, RAAF, force landed at a British airfield some miles away but the plane was so badly damaged that it was written off. Price was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his courageous performance and credited his crew's survival to the slow speed of his aircraft.

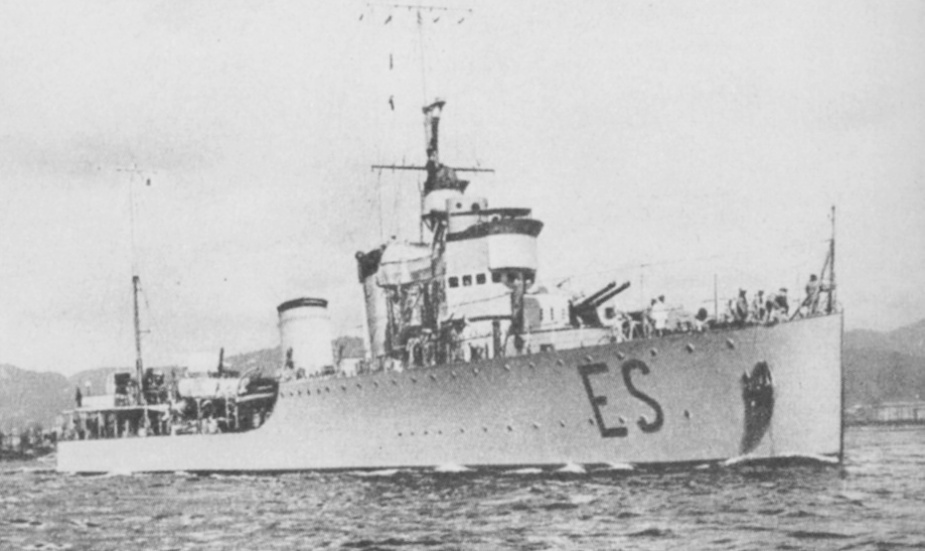

On 28 June Sydney was involved in the pursuit of three enemy destroyers detected by aerial reconnaissance which were engaged at long range. One of them, the Espero, was crippled by Sydney and Collins was ordered to finish her off and pick up any survivors. As he approached the stricken Italian vessel it opened fire with guns and torpedoes in a last brave act of defiance. Sydney's response was swift and final with her 6-inch guns soon reducing the destroyer to a burning wreck. The Espero then healed over and sank.

Captain Collins immediately ordered his boats away and the next two hours were spent rescuing survivors in the gathering darkness. When it became too dangerous for Sydney to remain in the area any longer, Collins instructed that one of his boats was to be fully provisioned and left behind to ensure that any survivors they had missed were given a sporting chance of survival. Those recovered by Sydney's crew were well cared for, to the extent that when it came time for them to disembark in Alexandria, many requested that they remain onboard as Sydney's prisoners rather than go to a Prisoner of War camp.

On 30 June the Seventh Cruiser Squadron came under several aerial attacks from Italian bombers during its return passage to Alexandria. This was to be the first of many that Sydney would emerge from unscathed, and in the weeks that followed she earned the reputation as a ‘lucky ship’. Later, in July, during a particularly virulent attack, Admiral Cunningham observed that Sydney completely disappeared in a line of towering pillars of spray as high as church steeples. When she emerged I signaled: “Are you all right?” to which came the rather dubious reply from that stout hearted Australian, Captain JA Collins, “I hope so”.

Battle of Calabria

The fleet next sailed from Alexandria late in the evening of 7 July and the following day came under intense air attack from the Italian air force. During one of these raids the cruiser HMS Gloucester was hit by a bomb which killed her captain and seventeen others. Later that evening a reconnaissance aircraft reported sighting two enemy battleships steering south about a hundred miles north-west of Benghazi. These capital ships were supported by six cruisers and seven destroyers and were later observed to alter course to the north. Cunningham immediately determined to maneuver his force between the enemy fleet and their base at Taranto to try and cut them off and bring them into action. The following day planes from the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle relocated the Italian ships and Cunningham's fleet closed them rapidly. At approximately 15:00 HMS Neptune, part of the vanguard of cruisers which included Sydney, reported sighting four Italian cruisers, and shortly afterwards the entire enemy fleet came into view, consisting of two battleships, twelve cruisers and numerous destroyers. The vanguard, greatly outnumbered, quickly found itself in action when the Italian heavy cruisers opened fire on them at 15:14.

Cunningham, in HMS Warspite, soon came to the assistance of the beleaguered cruisers and the battleship's fire forced the enemy to retire under the cover of smoke, after which there was a lull in the action. By then, the battleships HMS Malaya and Royal Sovereign were approaching the scene of action as were the British destroyers which were concentrating for an attack.

Shortly before 16:00, at a range of roughly thirteen miles, Warspite opened fire on the two enemy battleships and succeeded in straddling them. Moments later the Italian flagship, Guilio Cesare, was hit by a 15-inch shell from Warspite causing the Italians to turn away under a dense screen of smoke.

Meanwhile, the Allied cruisers had rejoined the action and were attempting to close the enemy destroyers. By 16:40, however, the engagement was all but over, and while it did not culminate in the much anticipated full scale Fleet action, Sydney had again been in the thick of it and survived unscathed with no casualties and only a few of her signal halyards shot away. During the action she expended over 400 rounds of her 6-inch ammunition and by the time she returned to Alexandria she had expended her entire outfit of 4-inch anti-aircraft ammunition beating off air attacks.

These attacks came as the Battle Fleet chased the Italians to within twenty-five miles of the coast of Calabria before breaking off the pursuit and altering course for a position south of Malta. The Fleet continued to be harassed from the air as it made its way back to Alexandria where it arrived on 13 July. There Sydney docked briefly for hull maintenance and to take on ammunition before her next patrol.

Back in Australia, Sydney's exploits in the Mediterranean were followed with fervor and within weeks she was to make headlines that would see her become a household name.

Battle of Cape Spada

On 18 July, Sydney sailed from Alexandria in company with the destroyer HMS Havock bound for the Gulf of Athens. Together they had orders to support Commander H St L Nicolson’s destroyer flotilla consisting of HMS Hyperion, Hero, Hasty and Ilex in the Aegean Sea. Nicolson was to intercept any Italian shipping attempting passage to or from the Dodecanese and also carry out an anti-submarine sweep from east to west along the north coast of the island of Crete.

Collins, realizing that Nicolson's westward sweep might expose him to enemy attack in the restricted waters of the Aegean, adjusted his course and speed so that he was better placed to provide support if required. In pre-radar days, dawn was often the most dangerous time of day and on 19 July this was to prove to be the case when Nicolson, at the western end of his sweep, sighted two enemy Condottieri Class cruisers which soon opened fire on his destroyers. With little choice other than to turn and run, and not knowing that Sydney and Havock were closing his position, Nicolson made an enemy contact report and began a speedy retiring action towards what he believed to be a far distant Sydney. Collins, hundreds of miles closer than anyone realised, prepared his ship for action but maintained strict communications silence so as not to alert the enemy to his presence. At 08:20 the two Italian cruisers were sighted and eight minutes later, with tension mounting, Sydney hoisted her battle ensigns and opened fire at a range of approximately ten miles. Both the enemy and the fleeing British destroyers were taken by surprise at the sudden appearance of Sydney and before long hits were registered on one of the enemy cruisers, the Giovanni Delle Bande Nere.

By then Nicolson’s destroyers were in wireless contact with Sydney and the two groups joined forces north of Cape Spada. Sydney had scored hits on both enemy cruisers and it became apparent to Collins that they were attempting to retreat towards the Antikythera Channel under cover of smoke. The enemy gunfire become sporadic at that point of the action and one of the cruisers, later identified as the Bartolomeo Colleoni, was seen to be on fire and losing headway, before coming to a complete stop.

Two of Nicolson’s destroyers, Hyperion and Ilex, were subsequently ordered to finish her off and pick up survivors. They were later relieved by Havock which remained in the area until she came under the threat of enemy air attack. In all some 550 Italians, including her Captain, were rescued by the destroyers.

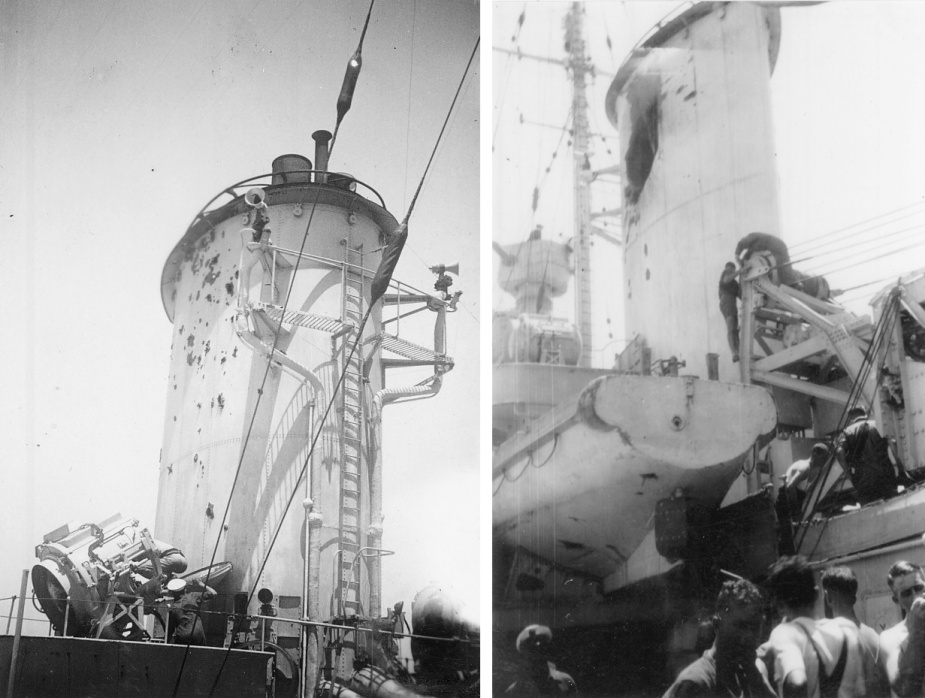

Meanwhile, Collins continued to chase the remaining cruiser, the Giovanni Delle Bande Nere. At 10:25, by which time Sydney was low on ammunition and coming within range of Italian bomber aircraft, Collins broke off the pursuit. During the action Sydney sustained just one hit to her forward funnel which caused only minor damage and no serious casualties.

Intent on retribution, the Italian air force was soon on the scene and doing its best to sink the Sydney which continued to lead a charmed life, escaping several very near misses. These attacks prevailed throughout the afternoon and Havock, now bound for Alexandria, was damaged in one of them, although not seriously. At 11:00 on 20 July Sydney entered Alexandria harbour with the Australian national flag flying proudly from her foremast and to the rousing cheers of the men of the Mediterranean fleet.

The Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Cunningham, boarded Sydney from his barge to personally congratulate Captain Collins and his crew. He was to recall in his memoirs:

For this fine, brisk action which showed the high efficiency and magnificent fighting qualities of the Royal Australian Navy, Captain Collins was immediately awarded the Companion of the Bath, by His Majesty, a well-deserved honour.

His report to the Admiralty concerning the action was similarly flattering, recording:

The credit for this successful and gallant action belongs mainly to Captain J.A. Collins, C.B., R.A.N., who by his quick appreciation of the situation, offensive spirit and resolute handling of H.M.A.S. Sydney, achieved a victory over a superior force which has had important strategical effects. It is significant that, so far as is known, no Italian surface forces have returned into or near the Aegean since this action was fought.

Throughout Australia news of Sydney’s victory dominated the newspapers. The Melbourne Herald of 20 July 1940 reported in its evening edition that:

Once again the Australian Navy has shown the splendid fighting quality and efficiency of the last war. Sydney outfought and destroyed the famous Emden and now her younger sister writes another page of naval history that will thrill the civilized world.

And thrill it, she did. Newspapers in London and New York enthusiastically acknowledged Sydney’s victory over the two superior Italian cruisers, while the Sydney Morning Herald of 22 July 1940 announced that:

Flags will be flown on all Government buildings throughout New South Wales today in honour of a great naval exploit.

With this victory, Sydney's aura of invincibility became cemented in the minds of the Australian people. On the other side of the world she had survived intense air attacks, taken on the might of the Italian Navy and snatched a decisive victory through a combination of initiative and bravado in the face of overwhelming odds. Her exploits were now becoming legendary. Almost every Australian community had one of its own serving in the cruiser and as she continued to add to her already impressive war record, so their pride in the ship, which Admiral Cunningham had dubbed a 'stormy petrel', continued to grow.

Note: This video is hosted on YouTube. Department of Defence users will not be able to view this video on the Defence Protected Network.

This cine film has been placed online as part of the Sea Power Centre - Australia's ongoing archival digitisation program.

Throughout the remainder of 1940 Sydney participated in further patrols, anti-submarine sweeps, convoy escort duties and shore bombardments in the Mediterranean and Adriatic. In January 1941 she received orders recalling her to Australia and as she departed Alexandria she received many farewell signals from the ships which she had fought alongside throughout 1940. Admiral Cunningham expressed his deep personal regret over her departure but also conveyed his hope that “your countrymen will give you the reception you deserve”.