Australian Naval Uniforms

Introduction

Modern navies mostly use camoflage utilitarian uniforms. In November 2008, a disruptive pattern navy uniform (DPNU) was first introduced in the Royal Australian Navy. A practical rig, it was far removed from the more traditional naval uniform popularised throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries. Today customary ‘sailor suits’ are reserved chiefly for ceremonial occasions, however, on those occasions when they are worn, they serve to remind Australians of the longevity of their Navy, its traditions and its consistent contribution to our nation’s maritime and economic security over more than 100 years.This article traces the origins of Australian naval uniforms following a process of continuous evolution as shifting social attitudes, new technologies, wars, and even religion have all influenced changes to the apparel worn by members of the senior service.

Origins

Australian naval dress descends directly from that worn by the Royal Navy (RN) in the late 19th century. When the Colonial Naval Defence Act 1865 was passed, which permitted the Australian colonies to raise their own naval forces, officers of the RN had been wearing a standardised form of uniform for over one hundred years. In the case of men, uniform for petty officers, seamen and boys, collectively known as ratings, was formally established in January 1857. Both officers and ratings of the RN, dressed in their smart blue or white uniforms, were recognisable the world over as belonging to the most powerful navy afloat and it was hardly surprising that the Australian colonies of Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and Queensland each decided that their infant naval forces should be similarly attired.

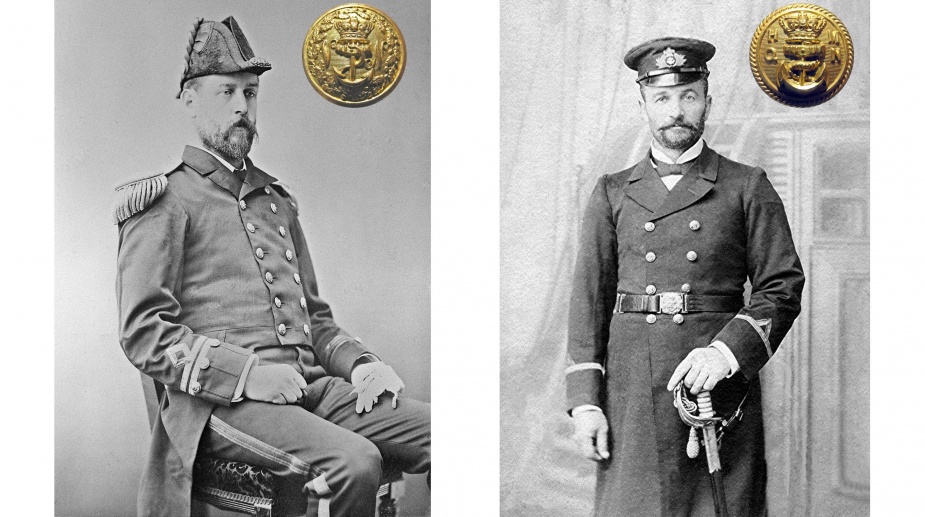

The Admiralty, however, concerned about certain legal aspects surrounding Australia’s new naval forces, was adamant that colonial naval officers and men were not to wear uniforms that could not be distinguished from those of the RN. Consequently, the colonies adopted RN uniforms but with minor alterations to rank lace, buttons and cap ribbons which satisfied the Admiralty’s requirement. These minor differences also served to distinguish one colonial naval force from another and before long a number of distinctive buttons, cap ribbons and a variety of rank lace featuring triangles, diamonds, crossed-anchors and stars began to appear throughout the colonies.

By the early 1880s the uniform that stylised the ‘sailor suit’ had evolved with seamen generally appearing in blue serge or white duck (heavy cotton) jumpers, frocks and bell-bottomed trousers. On frocks and jumpers a blue jean collar decorated with three rows of white tape was worn. Contrary to popular belief the white tape did not commemorate Vice Admiral Lord Nelson’s victories at the Nile, Copenhagen and Trafalgar for even the United States and German navies made use of this distinction from a very early time. Both jumpers and frocks were worn over a white, square cut flannel shirt, the neck of which was also bound with blue cotton tape. A black silk scarf worn around the neck and secured to the front of the jumper with blue or white tape tied in a bow added a certain amount of panache to the appearance of the wearer. The addition of a white lanyard, also worn around the neck and tucked inside the jumper completed the ensemble.

The rig was designed to be practical. The voluminous cut of the bell-bottom trousers enabled them to be removed rapidly, irrespective of footwear, and discarded to improve the chance of survival should a sailor go overboard. The seven horizontal creases ironed in each trouser leg enabled the garment to be concertinaed and rolled, inside out, so that they remained clean, taking up little room in lockers or kit bags. This method also prevented them from further unwanted creasing. The number of horizontal creases in each trouser leg was incidental although a popular belief emerged that the number was chosen to represent the seven seas.

The origin of the blue jean collar stems from the days of sail when it was popular for sailors to plait and tar their hair in a ponytail, the intent of the collar being to prevent the tar from staining the uniform beneath it. The black headscarf, that was once used to absorb sweat in crowded gun decks, is today worn only as a decorative feature comprising a strip of black silk secured by tapes and a bow to the front of the jumper. Also now decorative in nature is the white lanyard to which a seaman’s knife was once secured. In days gone by the knife would sit snugly in a pocket stitched to the front left breast of a seaman’s jumper. The pocket was later moved inside the jacket and out of sight remaining there until well after World War II. If the knife was required for use, the lanyard was slipped from around the neck and looped around one’s waist providing ready access.

Headwear for Seamen consisted of either a peak-less round blue or white cloth cap, or a straw sennet hat for use in hot weather. From 1868, all caps and hats worn by Seamen had black hat ribbons with gilt wire lettering bearing the name of their ship tied around them. The position of the bow securing the ribbon, however, moved variously and during World War I and II could often be found positioned over the left eye. Eventually it was decreed that all cap ribbons would be tied with the bow sitting neatly above the left ear.

Chief Petty Officers (CPO) were dressed in double-breasted long jackets fastened with gilt buttons, matching trousers and peaked caps of the same design as officers. The caps were embellished with a gilt wire badge depicting the sovereign’s crown above a rope-fouled Admiralty pattern anchor on a black background. For CPOs of the Seaman Branch, the crown was of gold and the anchor was of silver. For all others, both were of gold. Engine room artificers had one further distinction; the background on which their anchor was affixed was purple instead of black.

Later, in July 1920, a new cap badge for CPOs was introduced into the RAN. The new badge featured a silver anchor surrounded by a narrow wreath of laurel leaves in gold, surmounted by the Tudor crown. Thereafter, the cap badge previously worn by CPOs was adopted by petty officers that had attained four years seniority. These badges continue to be worn to this day.

By 1890 the variety of uniforms available to officers was extensive with a uniform available for every conceivable occasion, ranging from the impressive double-breasted full dress uniform, to the uninspiring yet practical sou’wester foul weather hat. The late 19th century was also a time of great technological change. Sail was giving way to steam and wooden hulled ships were replaced by ironclads equipped with high calibre guns in lieu of cannons. With this new technology came the need for more specialised officers and ratings to man the ships and in a very short period of time a variety of new trades appeared throughout the navy. With these new trades came the introduction of non-substantive rate badges that were worn on the right arm to identify specific specialisations. Some of the earliest of these included gunners, stokers, artisans and signalmen. Substantive badges, denoting rank, were worn on the left arm along with good conduct chevrons.

Non Executive Officers’ specialisations were identified by different coloured distinction cloth worn between the gold rank lace on their sleeves or undress epaulettes. This gave them a colourful appearance, with Mechanical Engineers adopting purple cloth, Paymasters white, Surgeons red and Electrical Engineers green, to name just a few. It is from the green that the term ‘greenie’ originates which remains in use to this day to describe any personnel of the Electrical Branch. Officers of the Medical and Dental Branches continue the tradition of wearing distinction cloth to this day primarily to identify them as non-combatants. Officers of the Executive Branch have traditionally worn none.

The Commonwealth Naval Forces

On 1 March 1901, the Australian States transferred their naval forces and all persons ‘employed in their connexion’ to the Federal Government, creating the Commonwealth Naval Forces (CNF). There were no immediate changes to uniforms and for a period the CNF was a consolidated navy in name only, with each state continuing to wear their former colonial uniforms. It was not until 1904 that new uniform regulations were promulgated. These instructions ordered officers of the CNF to wear the uniform prescribed in the King’s Regulations for officers and men of the RN with only minor modifications to rank lace. This involved the substitution of a triangle in place of the executive curl for Seaman Officers and the substitution of a gold star for officers of non-executive branches such as paymasters and engineers.

Petty Officers, men and boys, adopted the same uniform as that worn in the RN with the exception that cap ribbons were lettered H.M.A.S [His Majesty’s Australian Ship] followed by the name of their ship. This early reference to use of the letters ‘H.M.A.S’ preceding ship’s names is noteworthy, as it was not until 1911 that King George V officially approved the designation ‘His Majesty’s Australian Ship’.

The Royal Australian Navy

The granting of the Royal title in 1911, coupled with the arrival of the Australian fleet unit in October 1913, removed any lingering concerns the Admiralty held concerning Australian naval men wearing RN uniform and in 1913 the RAN received approval to adopt the full range of uniforms, badges and insignia of the RN. The only differences that remained between the two were minor changes to buttons and cap ribbons referencing Australia. For many, this was viewed as the final affirmation that Australia’s naval forces, as the embryonic RAN, had come of age. 1913 also saw the formation of the Naval Dockyard Police and the first permanent RAN band that paraded dressed in a version of the uniform worn by the Royal Marines Band Service.

In 1914, as war clouds gathered, the rank of Lieutenant Commander was introduced taking its place in the hierarchical structure above Lieutenants and below Commanders. This saw the familiar ‘half’ stripe introduced between the existing rank-lace worn by Lieutenants. It did not take long for those serving in the lower deck to coin the term ‘two-and-a half’ to describe officers of that rank.

The following year saw Engineering Officers granted use of the executive curl on their upper rank stripe and by 1918 the remaining non-executive officers had received similar approval, although the practice of wearing coloured distinction cloth continued until April 1955.

Not all of the RAN’s personnel went to war in navy blue. Members of the 1st Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train, an engineering unit, served at Gallipoli and throughout the Middle East dressed in the olive drab uniform of the 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Commander LS Bracegirdle, RAN, saw a need to distinguish between the two forces and designed large, stockless anchor badges to identify them as sailors, these were worn in lieu of the army’s ‘Rising Sun’ badges.

Between World War I and the outbreak of World War II a variety of new categories made their appearance including divers and dental mechanics. CPOs uniforms were also altered slightly when approval was given in January 1926 for three large gilt buttons to be added to the cuffs of blue jackets and white tunics. The combination of buttons on the cuffs coupled with the wearing of non-substantive badges on the lapels of the blue jacket became synonymous with the CPO rank.

In March 1928 a new style of RAN button was introduced, comprising a vertical stockless anchor replacing the previously worn ‘lazy’ anchor. This style has endured to this day, albeit since 1953 with the St Edward’s crown in lieu of a Tudor crown.

The onset of war with Germany on 3 September 1939 triggered another technological revolution that saw the armed forces of the industrialised world rapidly advance in ways not previously considered possible. With new technologies and innovation came the requirement for a host of new categories in the RAN and a much more practical approach to dress. At the beginning of the war many battles were fought in what today would be considered to be ceremonial uniforms. By the war’s end, thousands of sun-tanned Australian officers and sailors could be found throughout the Pacific, with bare chests or clad in khaki open necked shirts, shorts and sandals.

World War II also saw the institution of the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) and the Royal Australian Navy Nursing Service (RANNS). From 1941, Australia’s first female sailors could be found performing a variety of critical jobs ashore dressed in navy blue jackets, skirts and felt fur hats. By the end of the war they too had added a more practical khaki coloured working rig to their kit that was better suited to the hot Australian climate.

The women’s services were briefly disbanded after the war but in 1951 the WRANS was resurrected. In the same year, post war kit was approved which saw the introduction of light blue embroidered badges for ratings and the distinctive tricorne hat for officers, CPOs and petty officers. Later the RANNS was also reinstituted and they too adopted their own distinctive uniforms and insignia, more befitting with their role as nurses.

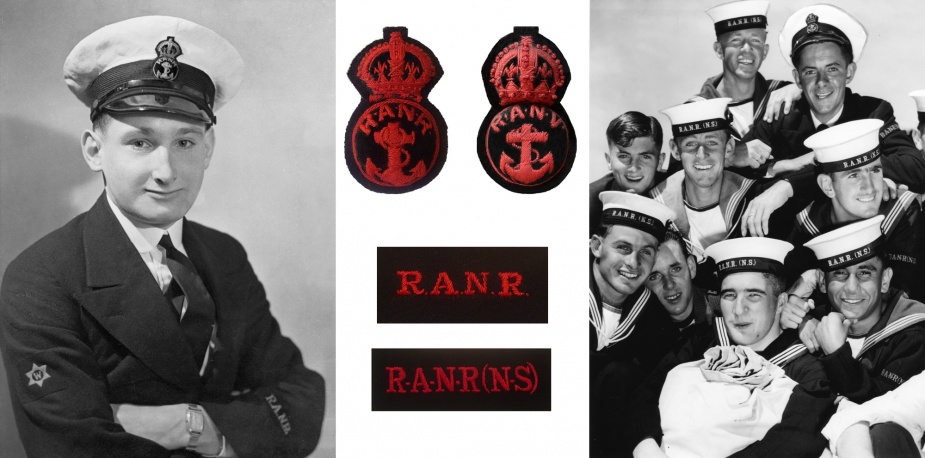

Australia’s reserve forces played a significant role throughout World War II serving in theatres the world over. Generally they wore the same uniform as officers and ratings of the permanent forces although officers were easily distinguishable by their waved rank lace that appeared in two different styles. One for the Royal Australian Naval Reserve Seagoing (RANR(S)) and another for officer of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve (RANR) and Royal Australian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RANVR). All were coined to be officers of the ‘wavy navy’ because of their distinctive rank lace.

Chaplains too, have been a constant in the RAN since its inception, although it took many years for them to gain approval to wear naval uniform. It was not until 1940 that a peaked cap and distinctive cap badge was approved for them to wear with a basic form of naval uniform replacing traditional clerical attire.

The lessons of World War II saw the RAN introduce a dedicated air arm into service and from 1947 a proliferation of new trades and specialisations began to appear. Soon pilots, observers, air crewmen, aircraft handlers, meteorologists, photographers, safety equipment personnel and myriad other air engineering trades swelled the ranks of the RAN. Flying clothing was introduced as were a host of new non-substantive rate badges and other items of uniform including the black wool beret.

In 1948 the electrical branch was instituted and with it came the first appearance of the familiar crossed lightning bolts on badges of the electrical category. Previously electrical duties had been discharged by men of the torpedo category.

Action working dress, comprising a light blue, long-sleeved shirt and dark blue cotton drill trousers, made its debut in March 1948. This practical hard-wearing working rig could be considered to be the forerunner of today’s DPNUs as it was one of the first uniforms to place practicality over appearance.

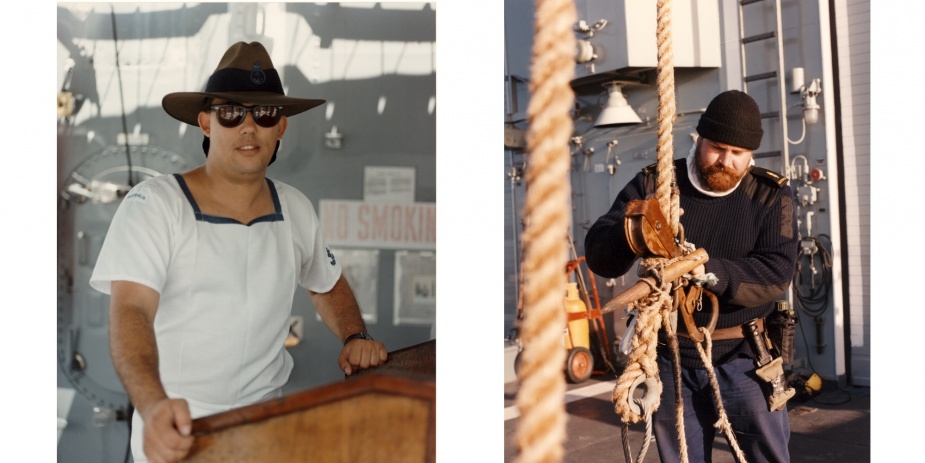

Another practical introduction followed in May 1950 when a new short-sleeved white bush jacket was introduced for officers of captain’s rank and above for use in tropical climates. Bush jackets remained an optional item of kit until 30 July 2009, at which time they were removed from the approved RAN clothing list. Today it is an optional piece of kit.

With the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 the RAN again found itself on active service. For those who served throughout the conflict it is often remembered for its freezing winter temperatures which saw many personnel resort to wearing warm civilian apparel in conjunction with their uniforms in an effort to keep warm, a lament of sailors since they first put to sea.

On 6 February 1952 King George VI died and Queen Elizabeth II ascended the throne. The change in monarch marked the end of over fifty years of rule by successive British kings, all of whom had adopted the Tudor crown as the symbol of their authority. After Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in June 1953, the St Edwards Crown was adopted, replacing the Tudor Crown on badges, insignia, buttons and accoutrements of the Commonwealth’s armed forces.

May 1952 saw the establishment of the Clearance Diving (CD) category and from September 1954, the letter ‘C’ was added below the diver’s non-substantive rate badge to indicate the CD qualification. The 1950s saw the demise of officer’s distinction cloth (with the exception of the medical and dental branches) and the abandonment of waved lace for officers of the reserve forces. They instead adopted a small letter ‘R’ which was centred in the loop of the executive curl. This too was done away with in 1986.

With the 1960s came the missile age and the beginning of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Between 1965 and 1972 elements of the RAN undertook continuous service in Vietnam as sea, ashore and in the air. Once again it was the environment in which RAN personnel were serving that influenced changes to uniforms, placing practicality ahead of appearance. Both clearance divers and aviators of the RAN could be found serving ashore in Vietnam dressed in army style ‘jungle greens’, while in ships on the gun line, officers serving in the RAN’s destroyers adopted the khaki uniforms worn by their counterparts of the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet. The 1960s also saw the RAN band shift out of their Royal Marine styled uniforms and into traditional naval rig.

On 25 July 1966 the Naval Board approved the introduction of a distinctive badge for wear by qualified RAN submarine personnel. The badge was of gold-plated gilding metal in the form of a brooch depicting two dolphins, nose-to-nose, supporting a crown. Its design is attributed to Captain AH McIntosh, RAN, (Ret'd). Since that time the badge has been proudly worn by thousands of RAN submariners who have earnt the right to wear it on their left breast.

The introduction of gilt metal qualification badges for submariners inspired a revision of the existing patterns for aircrew badges and in 1966 approval was given for gold plated, gilding metal badges to replace existing cloth flying badges.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the introduction of further new non-substantive badges, particularly for technical sailors whose badges were adorned with a variety of stars to denote technical expertise and skill. Specialist badges for principal warfare officers were also approved as were navy blue jumpers, known as ‘woolly pullies’, which made their debut in the mid-1980s. With them came the first of the RAN’s soft rank insignia that was worn on the shoulders. The disbandment of the WRANS followed and for the first time, women adopted the traditional uniforms of the sailor, as the RAN became one service.

The next major uniform change came with the advent of the first Gulf War when a need for a more robust form of action working dress was identified. This saw the introduction of grey, fire retardant, combat coveralls that were soon adopted throughout the entire RAN fleet. Around the same time, approval was also given for personnel serving ashore in operational areas to wear army disruptive pattern camouflage uniforms (DPCU). This was to become standard kit for officers and men of the clearance diving branch due to the nature of their work. A second variant, known as disruptive pattern desert uniform (DPDU), featuring sandy coloured tones better suited for operations in the Middle East Region followed and many naval personnel found themselves wearing this pattern while deployed ashore overseas.

In April 1997, sailors’ famous bell-bottom trousers and white flannels were discarded in favour of straight-legged pants and white collared shirts, subtly changing the traditional appearance of the Australian sailor.

Today the practicalities of naval service, recognition of cultural diversity and the wellbeing of RAN personnel take precedence over staunch traditional nautical appearance. A large percentage of officers and sailors now wear the familiar DPNU as their day-to-day working rig with the more traditional ‘sailor suits’ reserved for ceremonial occasions. Happily when the men and women of the RAN proudly don their ceremonial uniforms they continue to cut an inspiring sight reinforcing the traditions of over a century of service.

Further information concerning the history of Australian naval uniforms may be found in Kit Muster Volumes I & II, Uniforms, Badges and Categories of the Australian Navy.