Environment

Navy and the environment

The importance of sound environmental management in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) has long been acknowledged. For example, there is clear evidence the RAN has been issuing directives on the requirement to manage environmental risks at its primary Sydney Harbour base since 1920.

In our present era, this has assumed heightened importance, reflected in the following remarks by the Chief of Navy in issuing his guidance to Commanding Officers on environmental compliance in the RAN:

Navy is committed to implementing policies and procedures that contribute to the sustainable management of the environments in which we operate. We aim to ensure that operations are conducted effectively, while remaining aware of the need to protect our reputation.

In recent years, Navy has faced an increasingly complex range of environmental issues and regulations that impact on the way we conduct our business at sea, ashore and in the air. Within the broader framework of the Defence Environmental Policy, Navy has developed appropriate policy and guidance to meet these challenges. But compliance is not our only objective.

Effective and appropriate environmental management can result in financial and operational benefits to Navy, through savings in areas such as fuel, electricity, water and waste management cost, plus avoidance of costly contamination clean-up programmes, if we get things wrong.

Ongoing access to our vital offshore and land training areas in future will be determined partly by the way Navy demonstrates its environmental stewardship of these areas today.

Navy’s environmental responsibilities essentially mirror those of the other services and groups in Defence. The governing Defence policy direction is clearly articulated in the Environmental Policy Vision Statement issued by the Secretary and Chief of Defence Force and in the more detailed Defence Environmental Strategic Plan 2016-2036.

The RAN continues to respect and protect our natural environment and resources for the future of all Australians. Ongoing Navy operations around Australia’s coastline play a major role in this regard, by deterring fishing, and supporting the quarantine barrier that aims to stop arrival of threatening pests and diseases into the country. Recent reporting also demonstrates the valuable work done by some ships in detecting, then removing, ‘ghost’ fishing nets that have been abandoned on our waters, and which continue to harm various protected species.

Ashore, the RAN continues to play a vital part in preserving the natural and built heritage of many pristine locations where we are privileged to be based. Each establishment is required to have an Environmental Management Plan and working group involving all resident units, to oversee and advise on environmental issues. Continued environmental training in all RAN new entry and senior command/management courses aims to maintain an awareness of the need to manage the potential environmental impact of all Navy activities.

Managing impacts of Navy training activities at sea

The RAN is committed to ensuring that activities routinely conducted at sea are managed in a way that meets legislative obligations and community expectations. The Maritime Activities Environmental Management Plan (MA EMP) was developed to meet this commitment and is designed to cover all routine activities. It is a management strategy that simplifies any necessary environmental approvals processes, using a framework that has wide endorsement.

The MA EMP recognises that some key training areas (for example the West Australian Exercise Area - WAXA) are locations where a number of differing activities may be conducted simultaneously, or on a large scale. Accordingly, separate Planning Handbooks have been developed for these areas to assist exercise planners in considering the environmental implications of various activities in their area. Similarly, the MA EMP recognises that effective environmental management requires guidance at the planning phase. Planning Guides within the MA EMP provide advice on planning specific activities to avoid adverse environmental impact.

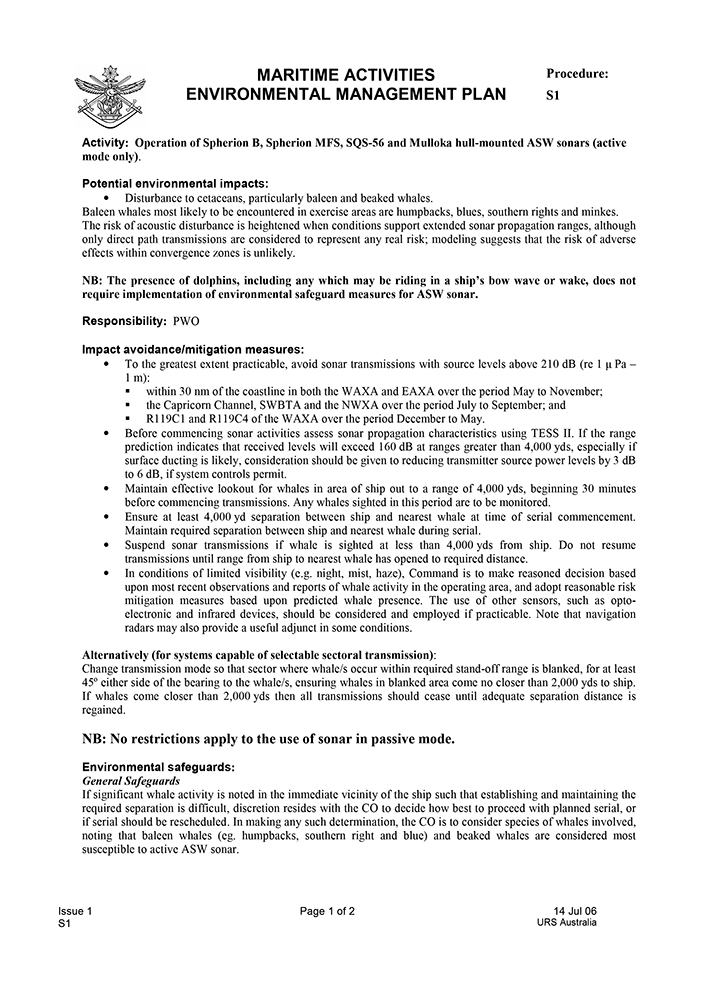

The MA EMP also recognises that the key to managing impacts is to manage individual activities as they occur. Real time management by operators at sea is facilitated by the use of Procedure Cards, which deal with the conduct of a wide range of activities (for example, the use of mid-frequency active sonar, or low flying by rotary wing aircraft).

Waste management

Both the Commonwealth Protection of the Sea (Prevention of Pollution from Ships) Act 1983 (POTS Act) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 (referred to as MARPOL 73/78), contain sovereign warship exemption clauses to avoid compromising the operational capability of such complex vessels. Warships are exempt due to their specialist roles, extreme space constraints, large numbers of embarked personnel and the increased occupational health and safety risk of retaining wastes onboard.

Despite these exemptions, the RAN has instituted rigorous waste management practices throughout the fleet, and has adopted most aspects of the MARPOL regulations, including specific shipborne waste directives for the disposal of oil, fuel and oily wastes (MARPOL Annex I), sewage (MARPOL Annex IV), garbage (MARPOL Annex V), and air pollution (MARPOL Annex VI).

RAN policy reflects a preference to avoid overboard discharge, for both environmental and tactical reasons, and seeks to dispose of wastes at shore facilities whenever operationally feasible. Where retention on board is not practicable, all RAN ships and support craft, including those operated by contracted organisations, are required to meet standards that mirror those applying to commercial and private vessels. This includes a prohibition on dumping of plastics at sea and limitations on disposal of other garbage streams depending on the location and distance from shore. Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas (eg. the Great Barrier Reef region), MARPOL Special Areas (eg Antarctica) and Marine Protected Areas (eg. Ashmore Reef) are subject to more stringent controls on waste discharge. The RAN complies with these.

Larger RAN ships are equipped with modern waste management equipment. This is backed up by contracted services to remove shipborne wastes in all ports where receiving facilities are available. The RAN is further committed to updating and improving shipborne systems to manage waste streams as new technologies emerges.

Biosecurity - Potential Marine Pests

Potential Marine Pests (PMPs) are plants or animals that are not native to Australia and have the potential to cause significant impact on our marine industries, environment and well-being. Marine pests have been introduced to Australia and moved around by a variety of human and natural means. Potential modes of transport for marine pests that affect RAN ships include ballast water (water carried by ships to ensure stability, trim and structural integrity) and biofouling (marine organisms that attach to objects immersed in salt water such as vessels’ hulls, internal cooling and fire fighting systems, ropes, anchors and other equipment).

The translocation of non native species can seriously affect native species if the introduced animal is able to prey on or out-compete the natives for food or other resources. A good example of this is the Northern Pacific Sea Star, which is now established in a number of locations in southern Australia. It is believed to have been introduced on the hulls of commercial and recreational vessels and is able to out-compete native species, leading to significant changes to the balance of native species in these areas.

Biofouling presents not just an environmental but a capability issue for ships. Fouling on a ship’s hull can result in increased drag, reducing the ship’s top speed and fuel efficiency. Fouling inside internal cooling systems can seriously affect the performance of air conditioning and other systems.

As a risk management measure, the RAN has adopted procedures to check the hulls of all ships before departure and on return from overseas deployments, to avoid introducing non-native species. The RAN also participates in Government forums on marine pests and liaises closely with Commonwealth and State/Territory authorities when necessary to control the risk of introducing or spreading marine pests.

RAN maintenance policies also aim to ensure that hull antifouling coatings are kept in good condition to minimise hull fouling growth. The RAN is also following international moves to manage the environmental impacts of antifouling paints, and met the 2008 deadline to eliminate use of TBT anti-fouling paints, consistent with the International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems on Ships, 2001.

For more information on PMPs, see the Department of Agriculture website at https://www.marinepests.gov.au/

The Great Barrier Reef

The RAN uses several important training areas in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) including Shoalwater Bay, Halifax Bay and Cowley Beach. Land and sea based exercises are regularly conducted in these training areas by both the Australian Defence Force and occasionally other visiting forces. Defence maintains close liaison with the GBRMP Authority on all aspects of operations in the Park, to ensure that these are conducted in a manner consistent with the park management plans and the Defence Environmental Policy.

Whales and sonar

The preservation and wellbeing of the increasing whale populations that migrate and congregate around Australia coastline is of considerable public interest. Its importance is emphasised by the fact that significant whale populations migrate annually through key Defence offshore exercise areas on the east and west coasts.

The potential effect of active sonar on marine mammals has attracted significant public interest and media attention internationally and in Australia in recent years. In summary, while the scientific evidence is still inconclusive, there is sufficient circumstantial evidence of a possible linkage between use of some mid-frequency active sonars and the stranding of (mostly) beaked whales in warmer northern hemisphere waters to justify a precautionary approach to such activity. This precautionary approach, which is reflected in the procedures adopted by the RAN in the MA EMP, aims to ensure that marine mammals are not inadvertently exposed to high levels of acoustic energy that might affect their health or interfere with behavioural characteristics that are important to their survival.

Despite the increasingly common sight of whales along our coastline and the spectacular recovery of humpback and southern right whale populations on our east, south and west coasts, researchers generally agree that we still understand relatively little about the habitat and behaviour of some whale species, notably the smaller and elusive beaked whales. Consequently Defence continues to support relevant research into marine mammal population biology and the effects of man-made noise on the ocean environment. This research will continue to assist Defence in reviewing and updating strategies used to plan and manage its activities in offshore areas, and to mitigate potential risks to marine mammals. Assisting the ADF to avoid any potential disturbance to marine animals during military training exercises is Defence Science and Technology (DST), who conducts research programs with experts at Australian universities and in collaboration with US scientists and the US Office of Naval Research.

Defence recognises that it must maintain the capability to fight and win at sea. The use of active sonar by the Navy remains an important operational requirement that provides warships with the ability to detect potentially hostile submarines. A combination of active and passive sonar systems is needed to detect increasingly quiet conventional submarines in likely operational areas for the RAN.

It is important to note, however, that regardless of any perceived risks to marine mammals, the use of active sonar by Navy frigates is infrequent - the sonar is usually only used during occasional exercises with submarines, or switched on briefly for a daily functionality check. Sonars are inactive at most times when RAN ships are at sea.

In 2003, the RAN proactively developed and adopted world leading management strategies to avoid harassing or causing harm to marine life. These procedures - embodied in the MA EMP - have been continually updated as new information has become available from research projects being undertaken around the world. The RAN remains committed to ensuring that effective management procedures are in place to avoid impacting on marine life.

Environmental impact assessments, strict mitigation measures and scientific research are just some of the tools that Navy employs to minimise its impact on marine mammals. The mitigation measures determine that if marine mammals are detected in close proximity to a Navy ship during an activity that might involve emission of high levels of underwater sound, either from sonar or underwater explosions, the ship or personnel concerned will relocate or delay the activity.

In Australia, populations of some heavily hunted whale species continue to increase, some by as much as 10% per annum, and may reach pre-whaling levels by 2025-2050. This pleasing level of recovery means that Navy personnel can expect to see increasing numbers of whales at sea in future, making appropriate management of interactions even more important. As the Chief of Navy has noted, “our future ability to co-habit and conduct essential operational training in offshore areas frequented by whales will be determined by the care and attention we give now to meeting our environmental management responsibilities at sea”.

More detailed coverage of Navy’s views on this issue is reflected in a Semaphore article published by the Sea Power Centre - Australia (Issue 5, 2007).

Obsolete Navy vessels

The RAN also accepts its environmental obligations when it comes to disposal of obsolete vessels. The primary aim of disposal of de-commissioned warships is to find an ongoing role for the vessel with a new owner. If this is not possible, the ship will likely be scrapped, sunk as a dive wreck or target, or gifted to a museum.

Defence bases

Defence shore based facilities and establishments including those occupied and used by Navy, are subject to a range of environmental compliance regimes under the Defence Environmental Management System. This includes ensuring that heritage buildings and places of natural or cultural significance are recognised and protected. All Defence bases are required to manage their environmental values and more information can be found at http://www.defence.gov.au/environment/ (external link).

Navy will strive to reduce its consumption of water and energy in all establishments, consistent with emerging community trends and the progressive initiatives under the Defence estate energy and water strategies.

The future

Environmentally sustainable performance at sea will be aimed at preserving Navy’s access to important offshore areas for the conduct of key training and exercise activities. Navy must adapt to increased compliance responsibilities and scrutiny of its environmental performance by Government and the community. Ashore and afloat, sound environmental stewardship and best practice must be second nature to all uniformed and civilian personnel.