The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force - First to Fight, 1914

Less than a year after the arrival of the Australian Fleet Unit in October 1913, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) was to make a substantial and significant contribution to Imperial security in the Pacific region. The diverse events that took place during 11-14 September 1914, although now largely forgotten in the annals of Australia’s military history, formed the cornerstone on which the RAN's enduring tradition of achievement has since been built.

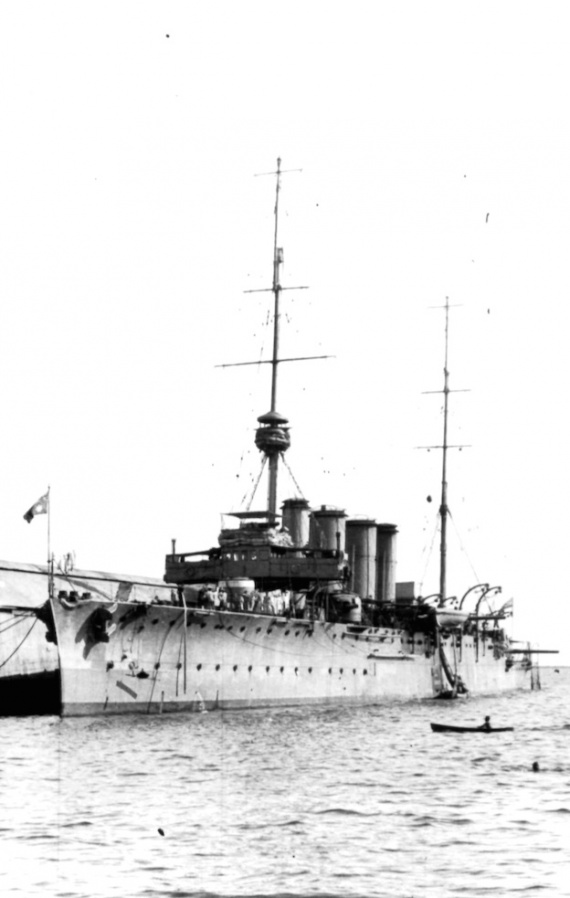

At the outbreak of war in August 1914 the Australian fleet comprised the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the light cruisers Melbourne, Sydney and Encounter, the small cruiser Pioneer, the destroyers Parramatta, Yarra and Warrego, and the submarines AE1 and AE2. The Commonwealth also possessed some ageing gunboats and torpedo boats from the former colonial navies. The permanent strength of the RAN at that time comprised 3800 personnel, of whom some 850 were on loan from the Royal Navy. The naval reserve forces provided a further 1646 personnel.

The first task of the RAN following the declaration of war was to seize or neutralise German territories in the Pacific stretching from the Caroline and Marshall Islands in the north, to New Britain and German New Guinea in the south. The British War Office considered it essential that Vice Admiral von Spee's East Asiatic Squadron of the Imperial German Navy should be denied the use of German facilities which represented a formidable network capable of providing intelligence, communication and logistic support to von Spee. Based in Tsingtao in China, the enemy squadron comprised the armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau and the light cruisers SMS Emden, SMS Nürnberg and SMS Leipzig.

Australia’s major effort was consequently directed at seizing German interests in New Guinea, and in particular New Britain which formed part of the German wireless network.

To achieve this objective a volunteer force known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) was hastily raised in early August 1914. It comprised eight companies of infantry, designated ‘A’ thru ‘H’, while 500 naval reservists and time-expired Royal Navy seamen drawn from Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia made up six companies of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve placed under the command of Commander JAH Beresford, RAN. Although many of those who volunteered for the infantry component had little or no experience in the military, the men of the naval forces were, in comparison, disciplined, well drilled in musketry, cutlass skills, field gun use and general field work, all of which was to place them in good stead for their impending mission.

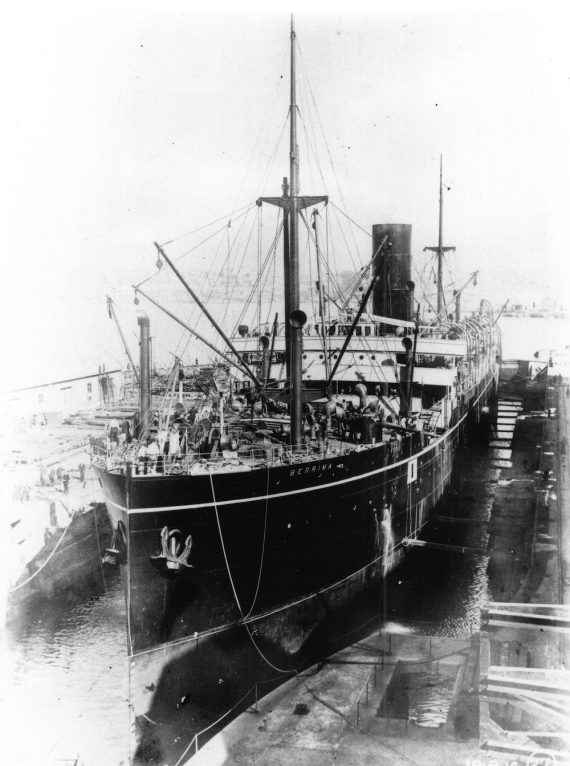

To convey the expeditionary force to New Guinea the Peninsular and Oriental liner Berrima was chartered by the Commonwealth Government as a transport. To equip her for this role she was refitted at Cockatoo Island, Sydney, in just six days, during which time accommodation was arranged in the holds for 1500 officers and men, with latrines, wash places and a hospital installed on the upper deck. Cabins were dismantled to provide guard rooms and baggage storage and four 4.7-inch guns were mounted to provide a measure of self protection, two on the forecastle and two on the poop deck. On 18 August the transport commissioned as HMAS Berrima under the command of Commander JB Stevenson, RN. Embarkation of the ANMEF began the same day, just seven days after the first volunteer had been enrolled.

Shortly after noon the following day, Berrima steamed out of Farm Cove, proudly flying the White Ensign as she made her way through the harbour toward Sydney Heads. On leaving Sydney she shaped a northerly course to Brisbane, stopping briefly in Moreton Bay before rendezvousing with the light cruiser HMAS Sydney (Captain JCT Glossop, RN) off Sandy Cape on 22 August. From there the two vessels proceeded in company to Palm Island, situated to the north of Townsville, where they arrived on 24 August. There Sydney handed over the escort responsibility for Berrima to the light cruiser HMAS Encounter (Acting Captain C LaP Lewin, RAN) which had arrived the previous day. Sydney then continued on to Townsville, arriving the same day, to take on provisions before returning to Palm Island on 26 August and resuming escort duties.

Palm Island was also the intended rendezvous point for the supply ship Aorangi (Lieutenant G Crawshaw, RANR), the submarine tenders Protector (Lieutenant Commander LAW Spooner, RAN) and Upolu (Lieutenant T Moore, RANR) and the submarines AE1 (Lieutenant Commander TF Besant, RN) and AE2 (Lieutenant HHG Stoker, RN). However, the submarine group was delayed and only Aorangi arrived as expected.

It had at first been intended that the Berrima should be escorted by Sydney and Encounter to Port Moresby where she would be joined by SS Kanowna carrying a contingent of 500 volunteers from the citizen force’s Kennedy Regiment. However, as the whereabouts of Von Spee’s squadron was still unknown, strict orders were received from Rear Admiral Sir George Patey in the RAN flagship HMAS Australia (Captain SH Radcliffe, RAN) that the expedition was not to proceed north of Palm Island without a strong naval escort.

At that time Patey was involved in Australia’s first coalition operation in company with HMAS Melbourne (Captain M L’E Silver, RAN) HMS Psyche, HMS Philomel, HMS Pyramus and the French cruiser Montcalm. Patey’s task was to escort a force of 1400 New Zealand troops to occupy German Samoa. Faced with this force the enemy colony surrendered without a fight. Melbourne was then ordered to the German territory of Nauru to destroy its wireless station where, on 9 September, she landed 25 naval personnel who arrested the German administrator and destroyed the already disabled wireless equipment.

The time spent waiting off Palm Island for orders to continue their passage proved to be an important interregnum for the men of the ANMEF, as it presented an opportunity to rehearse landing ashore by boat and for the men to hone their musketry and field skills.

On 2 September Sydney, Encounter, Berrima and Aorangi received orders to sail for Port Moresby where they arrived on 4 September to take on coal and oil and rendezvous with the remainder of the RAN fleet, the Kanowna and several colliers. While in Port Moresby the ANMEF’s military commander, Colonel W Holmes, inspected the men of the Kennedy Regiment who, although full of enthusiasm, were deemed to be unprepared and ill-equipped for active service. Consequently he recommended that they be returned to their home state. It transpired that the matter was resolved for him when the firemen in the ship in which they were embarked, the Kanowna, mutinied, refusing to carry out their duties. This demonstration was centred on them having not volunteered for overseas active service. Kanowna was subsequently ordered to proceed directly to Townsville, taking no further part in proceedings.

The rest of the force, then comprising Sydney, Encounter, Parramatta (Lieutenant WHF Warren, RAN), Warrego (Commander CL Cumberlege, RAN) Yarra (Lieutenant S Keightley, RAN), AE1, AE2, Aorangi, Berrima, the oiler Murex and collier Koolonga sailed on 7 September, bound for Rossel Island and a rendezvous with HMAS Australia which took place two days later. There Admiral Patey, Colonel Holmes, Captain Glossop, Commander Stevenson and Commander Cumberlege, of the destroyer flotilla, discussed the final plans for the attack on German New Guinea culminating in the release of an operational order for an attack on Rabaul.

Two points had been chosen for the landings, one at Rabaul, the seat of Government, the other at Herbertshöhe on the Gazelle Peninsula, New Britain. It was decided that the naval contingent should undertake the landing at Herbertshöhe. Patey’s orders were that should a preliminary reconnaissance of Blanche Bay reveal it to be empty of enemy ships, Parramatta was to examine the jetty at Rabaul and report whether Berrima could berth there. Sydney, which had embarked 50 men of the naval contingent prior to sailing from Port Moresby, would meanwhile transfer 25 of them to the destroyers Warrego and Yarra for landing four miles east of Herbertshöhe. The remaining 25 remained in Sydney to be landed at Herbertshöhe along with a 12-pounder gun. From there they would proceed inland to locate and destroy the enemy wireless stations. Intelligence indicated that two enemy wireless stations were operating in the area, one inland from Kabakaul at Bitapaka and the other at Herbertshöhe.[1]

The operation from the sea moved according to plan when the destroyers entered Blanche Bay at 3:30am on 11 September while Sydney guarded the entrance. The possibility that Von Spee’s squadron may have been lying in wait had not been discounted, and tension was understandably high as the small ships slowly entered the bay. In an effort to reduce their silhouette the destroyers had been painted black by their crews and splinter mats had been affixed around their bridgeworks to afford personnel a measure of protection. It transpired that there was no sign of the enemy cruisers and Parramatta reported that the Rabaul jetty was fit for berthing Berrima.

At 6:00am Australia escorted Berrima into Karavia Bay, where the former lowered her picket boats to sweep for sea mines. On completion Australia returned to sea to protect the approaches to the bay and cover the unfolding operation ashore.

The initial landings, in what would became Australia’s first joint force operation, took place at dawn on 11 September 1914 when 25 Petty Officers and men under the command of Lieutenant RG Bowen, RAN, were landed from the Australian destroyers at Kabakaul with instructions to seize the wireless station at Bitapaka. With Bowen were Midshipman RL Buller, RANR; and Captain BCA Pockley of the Australian Army Medical Corps. They were soon reinforced by Gunners STP Yeo and CF Bacon and ten men sent ashore from Warrego and Yarra who were put to immediate use maintaining communications between the advancing landing party and the beach.

Bowen’s party was soon striking inland through dense jungle to secure their objective when a scouting party, having deviated from the main road, found itself directly in the rear of the German first line of defence comprising three Germans and 20 native soldiers. The German in charge, Sergeant-Major Mauderer, was shot and wounded by Petty Officer GR Palmer, RANR, and after a short skirmish the enemy surrendered.

The wounded Mauderer was given first aid before being directed by Lieutenant Bowen to walk ahead of the main body of Australians and announce in German that 800 troops had landed and that his comrades should surrender. Bowen’s deception was rewarded, for word filtered back to the commander of the German defences, Captain von Klewitz, that a superior force had landed.

Believing himself outnumbered, Klewitz consequently ordered a withdrawal of his forces inland, resulting in the break down of the entire scheme of German coastal defence. This left only Bitapaka’s defenders offering active resistance. At this juncture Captain Pockley drew Bowen’s attention to the worsening condition of Mauderer who he subsequently treated in the field, resulting in the amputation of his badly wounded hand.

Following this initial skirmish Bowen reassessed his party’s position, sending Midshipmen Buller back to Kabakaul with the prisoners and instructions to send up reinforcements. Fifty nine men were subsequently drawn from the two destroyers, 14 armed with rifles and the rest with cutlass and pistols under the command of Lieutenant GA Hill, RNR.

This force reached Bowen’s group at about 10:00am to find them halted by a series of enemy trenches, under fire from snipers positioned in the trees and with two of their number lying mortally wounded.

The first to have fallen was Able Seaman WGV Williams, who formed part of the communications link between Bowen’s party and the beach. After observing natives in a coconut plantation beside the road Williams called up the man next to him, Stoker W Kember, to investigate. As Kember did so Williams covered him. The natives were found to be hoeing among the palms seemingly presenting no threat. Williams then went ahead and was shot in the stomach from a concealed position in the bush. Kember rushed to his aid, carrying him for nearly half a mile back along the road.

Captain Pockley had just finished treating Mauderer when he learned that Williams had been shot. Escorted by Officer’s Steward AO Annear, the two set off to find the injured sailor. On locating him he instructed Kember and another to evacuate the injured man to the rear, at the same time removing his red-cross brassard and tying it around Kember’s hat to afford him a measure of protection. Pockley and Annear then set about returning to the front but also came under fire. After taking cover Pockley tried to move forward again but was shot and seriously wounded. Some time later he was evacuated and transferred to the Berrima where both he and Williams died later that afternoon.

Meanwhile Bowen and Hill agreed on the next phase of the operation and set about outflanking the enemy. However, as the new advance began Bowen himself was seriously wounded by a sniper, leaving Hill to take command and renewing a call for reinforcements.

At Kabakaul, Hill’s request for support was received by Commander Beresford who ordered No. 3 Company (Lieutenant OW Gillam, RANR) and No. 6 Company (Lieutenant TA Bond, RANR) of the Naval Reserve as well as a machine gun section (Captain JL Harcus) to land. Beresford himself then relocated ashore and was accompanied by Captain RJA Travers, an Army intelligence officer.

Lieutenant Commander CB Elwell, RN was also landed, taking command of half of No. 3 Company and pushing ahead at best possible speed. Lieutenant Gillam followed with the other half in support. The conditions ashore were becoming increasingly difficult. The sun was high in the sky, the day windless, the heat stifling and the road dusty which made for hard going in the jungle terrain.

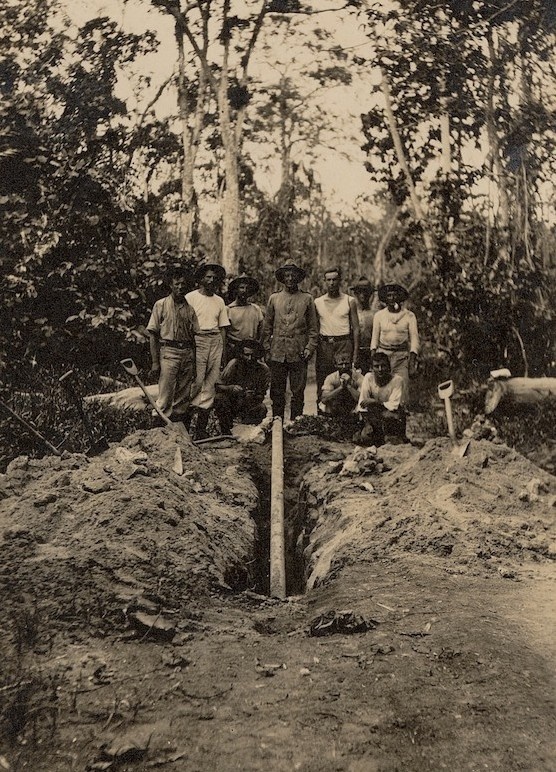

As Elwell’s party advanced Able Seaman JE Walker (who enlisted and was known at the time as Able Seaman Courtney) was shot dead near a sharp bend in the track, becoming the first Australian to be killed in action during the Great War. Two of Gillam’s men, Signalman RD Moffatt and Able Seaman DS Skillen were also hit, Moffatt succumbing to his injuries the next day. It was around this time that Gillam’s men also discovered the presence of wires laid through the bush that was correctly assumed to lead to a land mine buried beneath the road on which they were advancing. The wires were subsequently cut and a serious threat to the advance removed.

At about 1:00pm, Elwell’s party arrived at Hill’s position who was receiving enemy fire coming from a trench positioned ahead of him. There Elwell assumed command ordering Hill to take charge of a flanking movement on the left while he took charge of a similar movement on the right.

Elwell slowly led his men forward until they were less than eighty yards from the German positions. There they fixed bayonets and charged in the face of rapid enemy fire. Elwell, sword in hand, was shot and killed leading this charge, leaving Hill to continue the attack with Lieutenant Gillam, whose timely arrival with the remainder of No. 3 Company carried the day.

The now overwhelmed defenders reluctantly agreed to the unconditional surrender of both the German forces and the wireless station. This was negotiated by Lieutenant Commander Beresford who then called for Lieutenant Bond, with No. 6 Company to be brought up to advance with Captain Harcus and his machine gun section to secure the wireless station. Also in their company were Captain Travers, the intelligence officer, and two German prisoners, who preceded the party carrying a white flag of truce.

During their advance to the wireless station, Bond’s party encountered a series of enemy trenches. They successfully used the German speaking captives to negotiate the surrender of two of these, but met resistance at a third constructed at the top of a steep cutting at the side of the road. There, one of the German captives, Ritter, attempted to rally those who had already surrendered and a brisk exchange of fire followed during which two of Bond’s men, Able Seamen JH Tonks and T Sullivan were wounded and Able Seaman HW Street killed. Ritter and several of the natives fighting for the Germans also died in this exchange.

Leaving Harcus and his machine gun section to cover his advance, Bond accompanied by Captain Travers, Corporal CC Eitel, an interpreter from the machine gun section, and the remaining German, Kempf, walked on towards the wireless station. On the way they captured a German cyclist carrying a message to the Bitapaka garrison, and a horseman who was ordered to go ahead to the wireless station with news of the German surrender and a message that further resistance was futile.

At a police barracks 1000 yards from the wireless station a group of eight Germans and twenty native troops was encountered. The Germans were armed with magazine pistols and the latter with rifles. Through Kempf they were ordered to surrender but they refused to comply. At this point Lieutenant Bond warned Travers to stand by with his revolver before turning quickly towards the Germans and snatching their pistols from their holsters. So surprised were they by Bond’s sudden and daring action they were unable to defend themselves. The immediate surrender followed and the prisoners marched off toward the wireless station which was found to be abandoned.

For his courage and quick-thinking, Bond became the first Australian decorated during World War I, receiving a Distinguished Service Order.

News of the successful capture of the wireless station did not reach Admiral Patey until 1:00am on 12 September. At 3:00pm on 13 September the British flag was hoisted at Rabaul. The ceremony was held in an open space overlooking the harbour where the Australian fleet could be seen riding at anchor.

Within a few weeks most of the German territories in the area, including Bougainville and the Admiralty Islands, had been occupied without further opposition, at a cost of six dead and four wounded.

Sadly the success of the operation was marred by the disappearance of AE1 on 14 September while patrolling the narrow St George’s Strait between New Britain and New Ireland - the first RAN unit lost in wartime, the wreck of which was located in December 2017 in 300 metres of water off the Duke of York Island group.

Lest We Forget

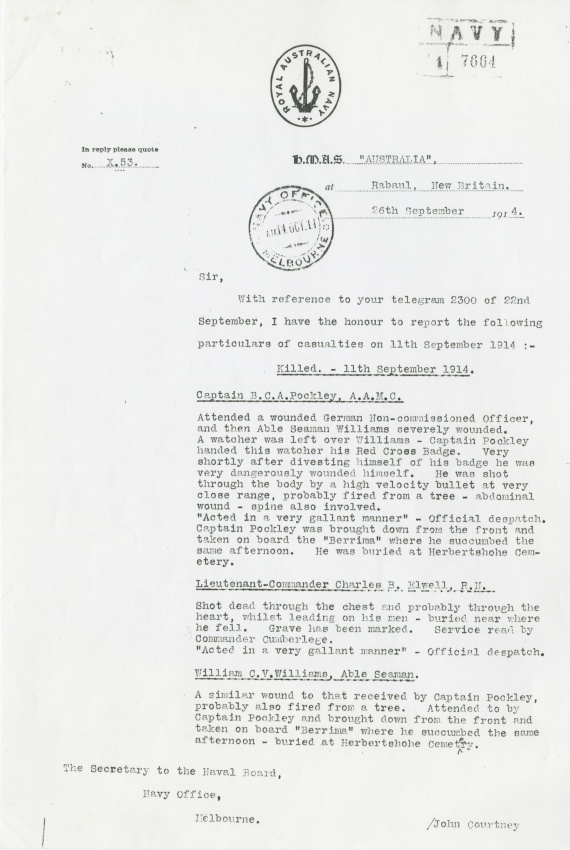

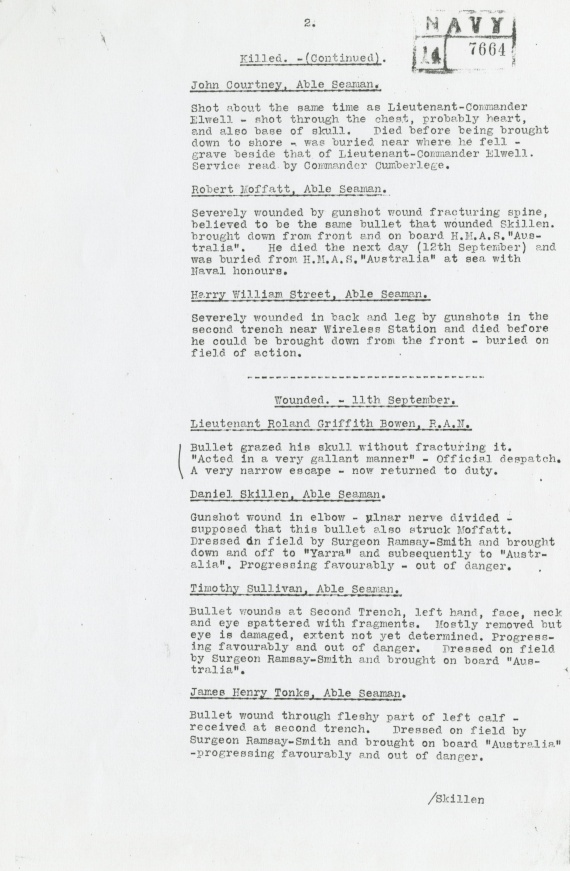

On 26 September 1914, Vice Admiral Patey submitted a report to the Secretary of the Naval Board detailing the particulars of those killed of wounded in the 11 September operation. A copy of that report is included below.

- ↑It was subsequently discovered that both were located at Bitapaka - one was the primary station and the other a secondary station.