Australians at Guadalcanal, August 1942

Whereas most Australians are familiar with the determined resistance and subsequent counter-offensive by Australian soldiers along the Kokoda Track, the concurrent actions of Australian sailors at Guadalcanal are often forgotten, but are perhaps equally as important to those who wish to better understand the fundamentals of Australian defence. After all, as an island nation, defence of our sea communications has always been vital. During late 1942, Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, which was situated alongside Australian sea communications with America, became the centre for the fight for Sea Control in the South and South West Pacific areas.

On 2 July 1942, the United States (US) Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered Allied forces in the Pacific to mount an offensive to halt the Japanese advance towards the sea lines of communication from the US to Australia and New Zealand. This led to the long struggle for control of Guadalcanal and neighbouring islands. Operation WATCHTOWER, the occupation of Guadalcanal and Tulagi, was the first offensive by the Allied Forces in the Pacific Theatre, and was the first US combined amphibious operation since 1898. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) contributed significantly during the early stages of the Guadalcanal campaign.[1]

The landings

Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley, Rear Admiral Commanding the Australian Squadron and Commander Task Force 44, was in command of the screening force at Guadalcanal, which included HMA Ships Australia (II), Canberra (I) and Hobart (I). His task was to protect the amphibious transports and the troops ashore from Japanese attacks from above, on, or beneath the sea. In addition, his ships were to bombard Japanese positions and provide fire support to the US Marines once ashore. A number of RAN Reserve officers, who were familiar with the waters of the Solomon Islands due to their civilian employment as merchant service masters, were able to help pilot the Australian and US ships through the poorly charted waters.

On 7 August 1942, the heavy cruiser Australia (II) commenced a pre-landing bombardment of Guadalcanal with her 8-inch guns. At 08:00 elements of the 1st US Marine Division, under Major General Vandergrift landed against strong Japanese opposition at Tulagi, while at 09:10 the main strength of the Marines landed unopposed at ‘Beach Red’ on Guadalcanal. The Marines of the first wave at Tulagi were accompanied by two RAN Volunteer Reserve (RANVR) officers who acted as guides.

Throughout the landing operations, combat air patrols and ground support aircraft were provided by three US aircraft carriers located to the south of Guadalcanal and controlled using a fighter-director team stationed onboard the cruiser USS Chicago. Crutchley also had eight cruiser-borne aircraft engaged in a continuous anti-submarine patrol as well as liaison work.

The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. The Headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) Eighth Fleet in Rabaul had detected increased radio transmissions in the area since the beginning of August so knew that the Allies were planning an operation in the area, but their interpretation was that there would be another US carrier raid in Papua. After receiving a signal from Tulagi at 06:30 on 7 August, the Japanese sent a force of medium bombers and fighters from Rabaul to attack the Allied Amphibious Force. A preliminary warning was sent by Petty Officer Paul Mason, a coastwatcher on Bougainville, at 11:37: “Twenty four bombers headed yours”. Consequently the Japanese aircraft had to contend with both carrier-borne fighters vectored to intercept them and the antiaircraft fire from Crutchley’s ship. At around 13:20, the high level bombers managed to drop their bombs but did no damage. A second attack by Japanese dive bombers scored a hit on one of the destroyers, USS Mugford; however, five out of the nine aircraft were destroyed by the carrier-borne fighters and ships’ anti-aircraft fire.

The Japanese raids continued the following day. Despite the Bougainville coastwatchers’ preliminary warning, a large force of twin engine ‘Betty’ torpedo bombers surprised the Allied fleet around noon, when they made their approach from the north east behind Florida Island. Four Japanese planes were destroyed by fighters from the carrier USS Enterprise on patrol in the eastern Nggela Channel, while the screen’s anti-aircraft fire brought down another 13. The destroyer USS Jervis was hit badly and had to leave the area, and nearby a burning Japanese plane crashed purposely into the transport George F Elliot with deadly results.

The US carriers had helped to save the transports, but they lost 21 planes in just two days. Their commander, Vice Admiral Fletcher, knew that he was commanding three out of only four US aircraft carriers in the Pacific. Fletcher signalled at 18:07 on 8 August: “Total fighter strength reduced from 99 to 78. In view of large number of enemy torpedo and bomber planes in area, recommend immediate withdrawal of carriers”. Fletcher’s recommendation to withdraw one day early (they had planned for three days with carrier air support) was a major concern for the Amphibious Force under Rear Admiral Turner, USN, for how could his transports and Crutchley’s screening force remain at Guadalcanal without air cover? The captured runway at Guadalcanal would not be fully operational until 17 August.

The Battle of Savo Island

The Guadalcanal invasion forces had weathered the Japanese air attacks of 7 and 8 August, but the IJN response, although taking longer to eventuate, was much more devastating. Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa commanding the Eighth Fleet was at Rabaul on the morning of 7 August when the signal describing the Tulagi attack arrived. Mikawa reacted smartly, ordering all available warships in the vicinity to assemble. By 19:30 Mikawa had available a squadron of seven cruisers and one destroyer: Chokai, Aoba, Kako, Kinugasa, Furutaka, Tenryu, Yubari and Yunagi.

Mikawa decided that his best chance of success against the Allied forces was to initiate a night surface attack. His cruisers had trained extensively in night gunfire and torpedo action, while he also knew that very few US aviators were proficient in night flying. Mikawa’s squadron steamed in line ahead at 24 knots through ‘The Slot’ in daylight on 8 August. They prepared for action and increased speed to 30 knots prior to making contact with the Allied forces guarding the approaches to Guadalcanal to the south of Savo Island.

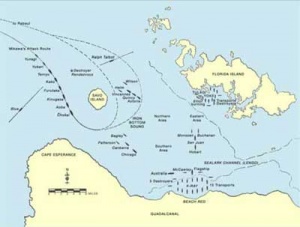

The Allied Screening Force was positioned in night dispositions around the amphibious transport groups off Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Two destroyers acted as radar picket ships to the west of Savo Island. The Sound off Guadalcanal was divided into three sectors. The Southern Force (south of Savo) consisted of the cruisers Australia (II), Canberra (I) and Chicago, and two destroyers. The Northern Force (north of Savo) consisted of the US cruisers Vincennes, Astoria and Quincy, and two destroyers. The eastern sector was covered by cruisers USS San Juan and Hobart, and two destroyers.

Unaware of the approaching Japanese, Turner convened a staff meeting onboard the attack transport USS McCawley. Crutchley departed the patrol area in Australia to attend the meeting and did not return to the Southern Force.

At 01:30 on 9 August, the Japanese force sighted one of the destroyer pickets, but the US destroyer’s crew did not detect the enemy ships. Japanese aircraft, launched from Mikawa’s cruisers some two hours earlier, dropped flares over the transport area, and these flares silhouetted the Allied ships on patrol south of Savo Island. At 01:37 on 9 August 1942, the Japanese squadron commenced firing on the cruisers Canberra (I) and Chicago. Canberra (I), the lead ship of the Southern Force, was hit by two torpedoes and the first of 24 Japanese 8-inch and 4.7-inch shells. She was immediately put out of action. Chicago was also badly damaged but still operational.

After disabling the Southern Screening Force the Japanese continued their sweep around Savo Island, split into two columns and approached the Northern Force. Again, complete surprise was achieved. They opened fire on the Americans at very close range and in only a few minutes the cruisers Quincy and Vincennes were sunk, and Astoria was severely damaged. The Japanese did not press home their advantage and began to withdraw. Mikawa’s decision not to engage the almost defenseless transports was a strategic error. Arguably he could have done so and thereby severely hindered the Allies’ strategic plan. However, in the ‘fog of war’, he preferred to retire, after gaining a major tactical victory, to avoid the threat of daylight counter-attacks by naval air and surface forces the following morning.

At dawn on 9 August 1942, the Allies could see the full extent of their losses. The Japanese had sunk the cruisers Quincy and Vincennes, while the cruisers Canberra (I) and Astoria were badly damaged and dead in the water. As the Australian cruiser could not raise steam, Admiral Turner ordered that she be abandoned and sunk. Once all survivors had been evacuated, USS Selfridge fired 263 5-inch shells and four torpedoes into Canberra (I) in an attempt to sink her. Eventually a torpedo fired by the destroyer USS Ellet administered the final blow. Despite extensive damage control efforts, Astoria also sank just after midday. Of the 819 men in Canberra (I) there were 193 casualties (84 killed, including Captain FE Getting). In the Allied Fleet there were approximately 2000 casualties overall (at least 1270 killed).

The Battle of Savo Island was one of the worst defeats ever inflicted on the United States’ and Australian navies. Canberra (I) remains the largest Australian warship ever lost in battle. The battle placed the occupation of Guadalcanal in jeopardy and delayed the completion of Operation WATCHTOWER for several months; however, it was not a strategic victory for the Japanese. The Allied forces did achieve their objective, which was to prevent the enemy reaching the transports.

The battles around Guadalcanal in late 1942 should be remembered. Not just because they were some of the most decisive actions of the Pacific Theatre, or because Australian naval forces fought alongside our American allies. They should be remembered because the Guadalcanal operations were instrumental in securing Australia’s sea lines of communication. The Kokoda Track was important to Australia’s defence, but had the Japanese taken Port Moresby their achievement would have had little strategic effect without also gaining Sea Control. On the other hand, Japanese attacks on our sea communications had the ability to stop our access to international trade and would have led to a rapid decline of Australia’s economy, political stability and military strength.

References

- ↑ G Hermon Gill, Australia in the War of 1939-1945. Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1968, pp. 112-157, provides a summary of the RAN’s involvement. Over 2300 Australians served in the Guadalcanal operations.

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Department of Defence

Canberra ACT 2600

seapower.centre@defence.gov.au