The Korean War

In the first decade of the 20th century, the Korean Peninsula was something of a pawn in power struggles between greater expansionist powers; primarily Japan and Russia. In 1910, after five years of provisional Japanese rule, Korea was annexed by Japan and a harsh colonial rule ensued. The Korean plight was largely ignored internationally until an agreement was reached at the Cairo Conference in December 1943 making Korean independence an Allied war aim. Later discussions at Yalta and Potsdam led the United States (US) and the Soviet Union to an agreement that Korea, upon the defeat of Japan, should be divided at the 38th parallel in order that the occupying Japanese could be disarmed. The type of government to be installed was not discussed.[1]

The decision to divide Korea had an unforeseen, and ultimately disastrous, consequence. A Soviet-backed communist regime was established in North Korea under Kim Il-sung, while United Nations (UN) sponsored democratic elections were held in the South. Relations between the two Korean governments were tense until finally, at 0400 hours on 25 June 1950, North Korean forces crossed the 38th Parallel and invaded the South. Two days later the UN Security Council requested assistance to defend South Korean sovereignty. Within days HMA Ships Shoalhaven (Commander Ian McDonald) and Bataan (Commander William Marks), along with the Royal Australian Air Force’s No. 77 Squadron, were placed at the disposal of the UN Commander, the US Army’s General Douglas MacArthur.

Kim Il-sung had hoped that the North’s initial superiority over the South on land and in the air would achieve a swift victory.[2] Thus, the UN’s complete control of the sea was critical in preventing the immediate fall of South Korea, enabling the UN to enforce a blockade, land ground forces, resupply units, bombard coastal targets and maintain a carrier based air campaign.

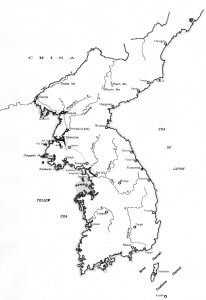

Korea’s geography, a peninsula with a mountainous central region and thousands of islands littering the coastline, makes the country particularly susceptible to influence from the sea. This does not mean that a maritime campaign is easy. Korea’s east coast is characterised by deep waters and a few islands making the area excellent for naval bombardment and the establishment of offshore raiding bases. The west coast, however, is characterised by shallow waters, extensive mudflats and islands, and large tidal movements that not only made navigation difficult, but also made it highly suitable for mine use by the North, a tactic that was employed with a measure of success. Most RAN operations were conducted along the difficult west coast.

At the outbreak of hostilities, Shoalhaven was deployed as the Australian naval contingent to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) in Japan while Bataan was en route to relieve her. Both ships were placed at General MacArthur’s disposal on 29 June 1950 and were immediately allocated to the Commonwealth naval force commanded by Rear Admiral William Andrewes, RN, which was later augmented by ships from Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands and France. This contingent operated primarily on the west coast though a number of frigates, including Shoalhaven, also performed escort duties in the east.

Six days after the invasion, Shoalhaven had the distinction of being the first Australian unit to carry out an operation, escorting the American ammunition ship USNS Sergeant George D Keathley into Pusan harbour on 1 July. It was Bataan, however, that fired the RAN’s first shot when, on 1 August 1950, she engaged an enemy shore battery near Haeju, north west of Inchon. Bataan had been taken by surprise by the gun battery while attempting to intercept some junks that were making for the coast at around 6:00 pm. Bataan returned fire and after a brief, but fierce, gun battle, made good her escape. The coxswain, Chief Petty Officer William Roe, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and Commander Marks was mentioned in dispatches for their parts in the action. All RAN ships undertook extensive shore bombardments throughout the course of the war.

HMAS Warramunga (Commander Otto Becher, DSC*) departed Sydney for the war zone on 6 August 1950 to relieve Shoalhaven. Shoalhaven had been attached to the BCOF for five months prior to being deployed to Korea and was badly in need of a refit. She was released on 1 September and Warramunga joined Bataan as part of the screening force for the aircraft carrier, HMS Triumph.

No sooner had Warramunga arrived in the war zone than the Naval Board began considering further rotations. The initial intention was for the ships to serve six months in Korean waters, however, just five years after the end of World War II, it became evident that maintaining two destroyers on station for six-month deployments was going to be extremely difficult. On 11 September, the decision was made to extend deployments to a full year.[3]

On 15 September, Bataan and Warramunga formed part of the covering force supporting amphibious landings at Inchon, engaging enemy coastal installations and gun batteries. The Inchon landings proceeded against the advice of General MacArthur’s senior staff officers and naval commanders who considered the risk of failure, and the possible consequences, to be too high. The landings turned out to be a resounding, if fortunate, success and thereafter resulted in significant Communist forces being tied down in coastal defence rather than reinforcing the main battleline. Large scale amphibious landings were not employed any further during the war, in spite of the UN forces’ obvious superiority, due to political concerns about the possible expansion of the conflict.[4]

Mine warfare was employed extensively by North Korean forces in the early months of the war. Mine clearing was particularly hazardous on the west coast due to the large tidal movements and the tendency of moored mines to ‘walk’. Thirteen UN ships were sunk or damaged by Soviet made North Korean mines in 1950. Warramunga’s Executive Officer, Lieutenant Commander Geoffrey Gladstone, was awarded both a bar to his Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) and the US Bronze Star for his skill and bravery in continually entering minefields in small boats to clear them.[5]

In addition to combat operations, RAN ships were also involved in humanitarian operations providing food and other supplies to islanders on the west coast who were struggling to survive in the midst of a war zone.

In early November 1950 with UN forces sweeping northwards, a swift end to the conflict appeared likely. However, China’s intervention in strength brought significant reversals on land before the end of the year, and by 4 January 1951 Seoul was back in Communist hands. Warramunga and Bataan were involved in the evacuations of Chinnampo and Inchon, which included a large number of civilian refugees. The difficulties of navigating the west coast were illustrated when Warramunga temporarily ran aground during the evacuation of Chinnampo where charts indicated that the ship should have had three metres of water beneath her.

As UN forces launched a counter-offensive early in 1951 and Communist forces were slowly pushed back over the 38th Parallel, a stalemate ensued. Peace talks began in Kaesong on 10 July 1951 but would drag on for two years. A show of naval strength in the Han River estuary, not too far from Kaesong, was ordered to pressure the North Korean delegation into a cease-fire. It was originally intended that this show of force would last for a few days; it ended up going for more than four months.

The Han River Estuary is a navigational nightmare; more than sixty kilometres of shallow channels weave through a maze of shifting mudbanks. Frigates were the only vessels with a draft shallow enough to navigate the estuary and with armament with enough range to hit the target area. Additionally, approaches to possible fire positions passed by enemy held shores and, potentially, enemy gun emplacements.

The operation commenced on 25 July 1951 when the frigate, HMAS Murchison (Lieutenant Commander Allan Dollard), which had relieved Bataan in May, entered the estuary with two other frigates, HMS Cardigan Bay and the South Korean PF 62 (although the South Korean withdrew shortly afterwards) and three small patrol launches. They quickly found that the waters in the estuary bore little resemblance to their charts and grounding became a very real hazard. Indeed Murchison did ground briefly on that first evening, though she fared better than Cardigan Bay which grounded three times. They did, however, carry out a bombardment that evening and then relied heavily on spotting aircraft from the carrier, USS Sicily, to navigate their way back out.

Much of the first two months of the operation involved re-surveying the channels in the estuary while conducting shore bombardments day and night. The North Koreans had evacuated much of the north shore of the estuary so resistance for the first couple of months amounted to little more than small arms fire from ashore. The first real counter-attack occurred on the 18th of September when a South Korean survey vessel was struck by a North Korean shell. Murchison and HMS Amethyst subsequently bombarded and silenced the enemy battery.

On the 28th of September Murchison embarked the commander of the UN Blockade and Escort Force, Rear Admiral George C Dyer, USN, to conduct an inspection of the forward channels. Dyer had clashed with the commander of the West Coast Blockade Force, Rear Admiral Alan Scott-Moncrieff, DSO, RN, over the operation. Dyer was a staunch supporter of the operation and urged UN vessels to push deeper, and further north, into the estuary. Scott-Moncrieff believed that the risks of the operation far outweighed the potential rewards. It was perhaps somewhat serendipitous, then, that Murchison faced the stiffest opposition of the operation with Dyer embarked.

As she entered a narrow channel near the mouth of the Yesong River, the frigate came under heavy fire from guns, mortars, machine guns and rifles concealed in nearby villages. The narrowness of the channel prevented Murchison from turning around; she had to continue on to the end of the channel, turn on her anchor, and come back through the kill zone again. The ship returned fire and scored direct hits on a 75mm gun emplacement and another on a trench, and inflicted heavy casualties. For her part, Murchison suffered only one man wounded.

Two days later she came under even heavier fire in the same area. She came under light enemy fire as she proceeded up a channel and, as she reached the end and turned, Lieutenant Commander Dollard ordered a bombardment as she proceeded back the other way. She was met with return fire of far greater ferocity then she had previously experienced. Several armour piercing shells penetrated the ship's hull, a 75mm shell exploded in the engine room, another shell went through the radar aerials and barely missed the ship's gunnery officer. Murchison return fire and destroyed several enemy gun emplacements.

The frigate made good her escape having been holed in seven places. Thankfully the shell which hit the engine room did no extensive damage. It's quite remarkable that Murchison suffered only three men wounded and one bofors gun put out of action.

The Han River operation petered out in November as peace talks effectively yielded the north-western part of the estuary to the North Koreans. Lieutenant Commander Dollard and Murchison’s navigator, Lieutenant James Kelly, were both awarded the DSC for their part in the operation.

Australia was one of just three nations to contribute a naval aviation component to the war effort. HMAS Sydney’s (Captain David Harries) deployment in October 1951, along with the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) Squadrons 805, 808 and 817, was a high priority for the RAN coming, as it did, so soon after the establishment of the FAA. Sydney conducted seven patrols, typically of nine flying days and one replenishment day, off both coasts during the course of the war.

Flying operations began on 5 October and six days later, Sydney’s Carrier Air Group set a light fleet carrier record by flying 89 sorties in one day.[6] Sydney’s main responsibilities included armed reconnaissance, army cooperation, naval gunfire spotting and combat air patrols. Most aircraft attacks concentrated on the enemy’s lines of communication and targets were typically things like railways, bridges and tunnels. The deployment was an unqualified success due in no small part to the efforts of flight deck and maintenance crews who worked exceedingly long hours in all weather conditions to ensure a high level of aircraft availability.

The Korean War ended with the signing of an armistice agreement on 27 July 1953. By conflict’s end, more than 4500 men aboard nine Australian warships had served in the operational area.[7] Three RAN members, all pilots from 805 Squadron,[8] lost their lives and six were wounded; 62 members received commendations. As a proportion of the Commonwealth contingent, the Australian contribution was third only to that of the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy.

RAN warships continued post-armistice patrols until June 1954. Fortunately, the Korean War never expanded into the global conflict that many feared at the time but it did provide the RAN with extensive tactical and logistic experience as part of a maritime coalition, experience which continues to serve the RAN well to this day.

References

- ↑ Woodbridge Bingham, Hilary Conroy & Frank W Iklé, A History of Asia Volume Two Second Edition, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, 1974, p. 659.

- ↑ Robert O’Neill, Australia in the Korean War 1950-53 Volume II: Combat Operations, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1985, p. 413.

- ↑ O’Neill, p. 425-426.

- ↑ O’Neill, p. 423.

- ↑ O’Neill, p. 430-431.

- ↑ David Stevens (ed), The Australian Centenary History of Defence Volume III: The Royal Australian Navy, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001, p. 177.

- ↑ Stevens, p. 173.

- ↑ Two other sailors, both from HMAS Sydney, died of illness contracted while in the Area of Operations.

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Department of Defence

Canberra ACT 2600

seapower.centre@defence.gov.au