Naming of RAN Ships

His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to approve of the Permanent Naval Forces of the Commonwealth being designated the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), and of the ships of that Navy being designated His Majesty’s Australian Ships.

So begins Commonwealth Forces Navy Order number 77 of 1911, dated 5 October 1911. This order granted the title ‘Royal’ to Australia's existing naval forces and formalised the use of the prefix ‘HMAS’ for all warships of the RAN. This prefix has changed only slightly from His Majesty’s Australian Ship, to Her Majesty’s Australian Ship when Elizabeth II became Monarch, and then reverted back to His Majesty’s Australian Ship upon the acsension of King Charles III.

But what of the hundreds of ships’ names that have followed this prefix and adorned the cap ribbons of our sailors and WRANS[1] since that time? How were these names selected? How might they be selected in the future? This Semaphore aims to answer these questions and provide the reader with an understanding of the evolution of the conventions used by the RAN when naming its vessels.

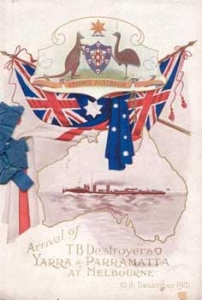

The first ships constructed for the Commonwealth Naval Forces, and thus the first Commonwealth naval vessels that required naming, were the three Torpedo Boat Destroyers (TBD) ordered by the Fisher Government in 1909.

In November 1909 the British Admiralty raised the question of naming the three destroyers and suggested that they be given names of Australian rivers. However, Senator Pearce, who was involved in the ordering of the ships, recommended naming them after eminent early

Australian navigators. Prime Minister Alfred Deakin decided against this and subsequently accepted the Admiralty's suggestion, with his Minister for Defence, Joseph Cook announcing that the three vessels would be known as Parramatta (I), Yarra (I) and Warrego (I) after Australian rivers bearing native names.[2] Cook’s announcement and preference for native river names reflected a distinct local identity and was an early acknowledgement of Australia’s Aboriginal heritage.

Three more TBDs were built at Cockatoo Island to complete the RAN’s destroyer flotilla; however, Cook’s preference for using native river names was only partially followed, with the three additional destroyers being named Huon (I), Torrens (I) and Swan (I).

The process of gaining approval for ships’ names was adopted from policy established by the Royal Navy (RN) whereby proposed names were forwarded through the Admiralty to the King for his assent. In 1926 this policy was deviated from when the Admiralty was presented with proposed names for two Australian O Class submarines. This was one of the first occasions that names had been submitted for submarines, which had hitherto been known by alpha numeric designations such as those given to the first Australian submarines AE1 and AE2. It transpired that as submarines were not considered ‘ships’ it would not be necessary to gain Royal assent. The ‘boats’ were subsequently named Oxley (I) and Otway (I) and on 22 June 1938 the Admiralty determined that only the names of fighting ships need be referred to His Majesty for approval.

On 7 February 1942 this policy was further revised when the Admiralty instructed that only names for ships classed as frigates or larger should receive Royal assent. This policy change came at a time when hundreds of ships and small craft were being requisitioned into war service throughout the Commonwealth with many of them retaining their original names. It was accepted that proposed names for Australian ships should continue to be referred to the Admiralty, although this was mainly to prevent duplication of names within Commonwealth navies. It was during this period that some of the RAN’s more colourful names came into being, with vessels such as Ping Wo, Whang Pu and Blowfly often raising people’s eyebrows when mentioned.[3]

By adopting British naming principles the RAN continued the practice of naming large ships, such as aircraft carriers and cruisers, after major cities and smaller ships, such as destroyers and frigates, after towns and rivers. The first RAN ships to bear the names of Australian capital cities were the three World War I, Chatham Class cruisers Sydney (I), Melbourne (I) and Brisbane (I), while the name of our great continent was reserved for the Indefatigable Class battle cruiser, and first flagship of the RAN, Australia (I). As warship design and capability has evolved, so have the conventions for the allocation of names, and today it is the destroyers and frigates that proudly bear the names of our capital cities.

Another important naming principle adopted from the Royal Navy was the practice of reusing names in later generations of ships in order to build tradition and foster a sense of esprit de corps among ships’ companies. Today, for example, the RAN has in commission the fourth ships to bear the name Sydney and Parramatta and the third ships named Stuart and Anzac. All vessels that inherit a name previously carried by a former RAN warship carry forth the Battle Honours won by their Australian predecessors, which are listed on an ornately carved wooden board normally displayed in the vicinity of a ship’s gangway.

There have of course been exceptions to these general naming conventions. Throughout the Australian Navy’s early history a number of ships were acquired from the RN that retained their original British names. Some of these names have been used in later classes of Australian warships to perpetuate the deeds performed by the officers and men who served in them. These include names such as Vampire, Voyager, Vendetta, Stalwart and Success to name but a few.

Guidance on current RAN naming principles can be found in Defence instructions,[4] which reflect a strong emphasis on promoting links between the Navy and the Australian community, with a preference to maintain a uniquely Australian identity. Joseph Cook’s early recognition of Australia’s Indigenous people has also been continued with several RAN warships bearing Aboriginal names, notably the Anzac Class frigates Arunta (II) and Warramunga (II).

Many factors are taken into consideration when selecting names for a new class of ship and this begins when the Chief of Navy (CN) calls for naming recommendations from the Naval History Section (NHS), Sea Power Centre - Australia. The first consideration when compiling potential names is the type and number of vessels being introduced into service. In general terms, surface combatants and patrol boats may be named after Australian cities, towns or districts while submarines may carry names with a uniquely Australian connection. In the case of the Collins Class submarines the names of famous Australian World War II naval personalities were used for the first time to acknowledge their outstanding service. Amphibious ships are usually named after Australian amphibious operations, battles or contiguous seas while mine warfare vessels may be named after rivers and bays. Smaller craft such as tugs adopt the names of Australian flora and fauna. All vessels may bear the name of a previous ship of a comparable class as is the case with Kanimbla (II) and Manoora (II).

Achieving a balanced distribution of names among Australia’s states and territories and reviewing the various representations received by CN from civil communities and ex-service groups to have ships carry a particular name is an integral part of the naming process. All of these representations receive careful consideration, irrespective of whether they have a specific link with the Australian community or not, and are appraised on the actual suitability of the name proposed and the service record and history of ships that may have carried the name previously.

The NHS then prepares a comprehensive brief for CN on proposed names, their history and the level of public interest. This brief normally contains names well in excess of the number actually required in order to provide CN with a variety of naming options. CN will then exercise the privilege of his position to make a final decision or, alternately, he may call for a further submission from the NHS.

Once CN selects the names, his recommendations are forwarded through the Minister for Defence and the Prime Minister to His Excellency the Governor-General for final approval.

The planned acquisition of three new Air Warfare Destroyers (AWD) and two new Amphibious Ships, coupled with the acquisition of the Armidale Class patrol boats has seen a variety of former names selected to return to use as well as one or two new ones. For example, the AWDs will be named Hobart (III), Brisbane (III) and Sydney (V) while the amphibious ships will be named Canberra (III) and Adelaide (III). Unfortunately there will always be more names available than there are ships to carry them and the decision to select a particular name is seldom an easy one. Currently all vessels planned for the future RAN fleet have now been named, but for those readers interested in the histories of some of our famous and not so famous ships please visit the RAN Ship Histories page on the Sea Power Centre - Australia web site.

References

- ↑ Womens Royal Australian Naval Service, see also Royal Australian Navy, ‘Women in the RAN: the Road to Command at Sea’, Semaphore, Issue 19, November 2006.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia, Hansard, 6 December 1909.

- ↑ HMAS Ping Wo and Whang Pu were both former Chinese river steamers requisitioned for wartime service. HMAS Blowfly was a survey launch.

- ↑ Department of Defence, Defence Instruction (Navy) ADMIN 4-4: Naming of Royal Australian Navy Ships, Establishments and Facilities, Canberra, 18 February 2005.

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Department of Defence

Canberra ACT 2600

seapower.centre@defence.gov.au