Petty Officer Humphries and the George Medal

The George Medal was established by King George VI in September 1940 primarily to honour civilian acts of courage. However it also served to recognise service personnel for acts of great bravery not conducted in the face of the enemy for which other military awards were not appropriate. When Petty Officer John T Humphries of the armed merchant cruiser HMS Kanimbla was awarded the new medal in early 1942, it was to be the highest decoration awarded to an Australian rating during World War II. Only nine members of the Royal Australian Navy received the George Medal during the conflict; aside from Humphries they were all naval officers.[1] He was decorated for his role in extremely hazardous diving operations while undertaking salvage work in Iran during late 1941.

John Humphries was born on 26 October 1903 in Sebastopol, a suburb in the Victorian town of Ballarat. He joined the RAN in July 1918 as a boy seaman in the training ship HMAS Tingira, and served through the 1920s in the battlecruiser Australia, the sloop Geranium, cruisers Melbourne and Sydney, as well as the destroyers Anzac and Warrego before discharging as a Petty Officer in 1928. He then moved to Brisbane and trained as a diver, working on the foundations of the Grey Street Bridge, and later undertook similar work on the Story Bridge where he received high praise for his courage and skill while performing this hazardous work. In 1938 he joined the Royal Australian Fleet Reserve and conducted periods of training at the Brisbane reserve depot leading up to the outbreak of war. In September 1939 he was called up and drafted to the Kanimbla as she prepared for overseas service with the Royal Navy.[2]

Kanimbla was a 10,985 ton Australian coastal passenger vessel completed in 1936. She was taken over by the British Admiralty upon the outbreak of war and converted to an armed merchant cruiser. Fitted with seven 6-inch low angle and two 3-inch anti-aircraft guns, she was manned almost entirely by men of the RAN Reserve. On 25 August 1941 Kanimbla found herself spearheading the capture of the Iranian Persian Gulf port of Bandar Shahpur as Britain and the Soviet Union mounted a joint invasion of the country. This British Empire operation, led by Kanimbla’s Commanding Officer, Captain William LG Adams, RN, targeted five German and three Italian merchant ships which had been sheltering in neutral Iranian waters. Code named BISHOP, the operation was an outstanding success with four of the German and all three Italian merchantmen being captured along with two Iranian gunboats. All of the Axis ships had attempted to scuttle themselves, but determined salvage attempts by the boarding parties saw all but one saved, the German Weissenfels sinking in deep water.

The Italians at Bandar Shahpur had opted to destroy their ships by setting them alight as best they could, while the Germans had opted for flooding, using demolition charges and by opening sea water inlet valves. At this point in the war, with Allied merchant shipping losses mounting, mainly to German U-boats in the Atlantic Ocean, the capture of enemy merchantmen to be pressed into British service had assumed considerable importance. The army’s capture of Bandar Shahpur had been a secondary consideration to taking the enemy ships intact. The crew of the Hansa Line’s freighter Hohenfels nearly succeeded in their intent to sink the ship as Kanimbla’s Number 1 Boarding Party battled to disarm explosive charges and isolate seawater inlet valves in the darkened and flooding engine room. This episode saw Engineer Lieutenant Colin Clark, Engine Room Artificer Frank Newman and Leading Stoker James Watson all Mentioned in Despatches. As the engineering section of the boarding party slowly lost their battle against rising waters in the engine room, the remainder on deck managed to raft two of the force’s tugs alongside the sinking ship and drive her upon a sandbank at the harbour’s edge. In the days after the assault, the captured Axis merchantmen that had remained afloat were either steamed under their own power, or towed, to the Indian port of Karachi. Meanwhile Kanimbla’s ship’s company set to work in Hohenfels on what would be the largest salvage job ever attempted under naval direction to that time, there being no chance of contracting the task out to specialists.[3]

Hohenfels was a sturdily built 7900 ton diesel powered cargo ship completed in 1938. Despite having been trapped in Iran by a British blockade since the beginning of the war with its cargo of 7500 tons of Ilmenite sand (used for case hardening steel), the ship had been very well maintained. She lay semi submerged in a precarious position on the edge of a steep bank of apparently hard clay with very deep water under her stern. At high tide the water level rose above her main deck flooding the fore and aft well decks. When her crew had tried to sink the ship, the scuttling charges that had been detonated in the holds were not well sited and did little more damage than loosening a few rivets. A small fire started in the engine room under a fuel tank had been easily extinguished by the Australian sailors. The opening of sea water inlet valves and the throwing of covers into the bilge had been much more successful.[4] Salvaging the ship would require significant diving work to enable her to be patched, pumped out and refloated. The salvage crew was led by Kanimbla’s engineer, Engineer Commander James McGuffog RANR(S), and they would live aboard Hohenfels in foetid conditions until the job was done.

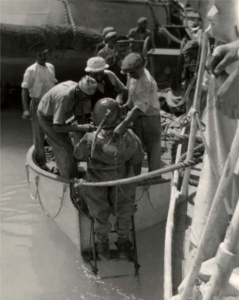

Despite not actually being qualified as a naval diver, Petty Officer Humphries volunteered to assist with the operation. Other divers were involved, but only he, and on an occasion when Humphries was ill, Royal Navy diver Able Seaman C Pask of the sloop HMS Falmouth, was willing to dive in the completely flooded engine room. Conditions for diving were treacherous; the water visibility in the crowded engine room being next to zero thanks to mud, leaking oil fuel and little natural light. Humphries had to descend into the space using traditional naval service diving gear comprising a steel helmet, diving suit, lead boots and belt with a hose to the hand operated air pump on the surface. The self contained diving equipment that would have been appropriate for this work was not available. He had no communications with his attendants whatsoever after reaching the first grating and turning to go down the second ladder. He was under no illusions that if his air supply should become fouled as he made his way through the darkened obstacle course of Hohenfels’ engine room, no one would know and his survival would be highly unlikely.

The German engineers had managed to open 13 individual valves allowing seawater to flood the engine room. Covers from ballast valve boxes and bilge suction valves for the five holds in the ship had been removed and thrown out of sight in the bilges. Both port and starboard sea water cooling injection valves were jammed open. Number 1 Boarding Party had managed, against the odds, to partially close off four of these flooding points along with securing the watertight door to the shaft tunnel but the majority were going to have to be closed by divers before pumping could be effective. Humphries’ descent was down a series of three long ladders to the top platform at the after end of the engine room then forward along the length of the compartment before going down two short ladders on either side to the bottom platform. At least 120 feet of air hose and shot rope was required to be paid out in order to allow Humphries to reach the bowels of the ship. He was the only diver able to make it that far. During each dive, Humphries made his way down the ladders between the two main engines and around the myriad equipment and fittings to locate the valves and covers before replacing and securing them.

Some valves needed to be plugged, while in the case of the main seawater cooling injection valves, plates had to be patched over their access gratings on the outside of the ship’s hull. The actual valves in the engine room were in such positions behind machinery as to be inaccessible to a man in full diving gear. In order to fashion plates to cover the approximately two feet by three feet steel gratings, a template of the hull shape was created by Humphries so Kanimbla’s shipwrights could manufacture the required steel coverings. In the words of Frank Newman who also assisted in the salvage operations:

Now, this guy had to take all of that gear down, place it down there, and he had to lie with half his face in the mud and...place [the] plate up, put the hooks through the grating...through the plate...[and] have the grommet in between and then the nuts on the outside...he did that job and it was brilliant.[5]

Working on the barnacle encrusted hull resulted in severe lacerations to the hands of all the divers which soon became septic. To make matters worse, all the diving suits were now suffering from serious leaks as the oil in the engine room caused them to perish.

Humphries dived within Hohenfels’ engine room for lengthy periods a total of 12 times, fully aware that he was taking his life in his hands on each occasion, he also dived in the ship’s holds to ensure that the bilge lines were firmly sealed in each. Aside from work in Hohenfels, Humphries undertook remarkably good work in another German freighter, the Marienfels. In his report of the salvage at the end of the operation, Captain Adams said of Humphries’ work, “It is almost impossible to imagine, without actually seeing this congested engine room, the astonishing and daring feats he performed” and “above all else, this personal courage...is only comparable in my view, with that of those men who work in bomb destruction squads in England.”[6]

Hohenfels was eventually pumped out and floated on 28 September before being manoeuvred alongside Kanimbla at Bandar Shahpur’s main jetty to commence unloading and preparations for towing. She finally left the Iranian port on 11 October 1941, arriving in Karachi nine days later. The ship was repaired and employed in assisting the Allied war effort under British and later Dutch control for the duration of hostilities, eventually being broken up in Hong Kong during 1962.[7]

Following the operation, Captain Adams recommended Humphries be awarded the rating of a Naval Diver by the Australian authorities, while the Commander-in-Chief East Indies, Vice Admiral Geoffrey S Arbuthnot RN, recommended direct to the Admiralty that he be considered for an immediate award due to his “gallant work” involving “a grave risk of death”. Petty Officer Humphries was awarded the George Medal on 17 February 1942, the citation reading “For skill, and undaunted devotion to duty in hazardous diving operations”. He was also rated as Diver 1st Class, backdated to 25 August the previous year, and later drafted ashore to HMAS Moreton in Brisbane in December 1942. Humphries left the Navy in May 1946, living the rest of his life in Brisbane until his death at age 83 on 23 August 1987.[8]

References

- ↑ Two medals to RAN and seven to RANVR personnel. Of the latter, three subsequently won bars to the medal.

- ↑ Gregory P Gilbert (ed), Australian Naval Personalities, Papers in Maritime Affairs No. 17, Sea Power Centre - Australia, Canberra, 2006, p. 111; and National Archives of Australia (NAA): A6770, Item Humphries, John Thomas.

- ↑ Owen E Griffiths, Cry Havoc, LC Publishing Company, Sydney, 1949, p. 4; and NAA: MP1049/5, Item 2026/3/455, Persian Gulf Operations, Report of Proceedings (RoP) of Senior Officer Force ‘B’ from 25 August 1941 to 5 October 1941.

- ↑ NAA: MP1049/5, Item 2026/3/455, Report on Salvage Operations carried out on the British, ex German, Prize Hohenfels; and RoP of Senior Officer Force ‘B’ from 10th August 1941 to 25th August 1941.

- ↑ NAA: MP1049/5, Item 2026/3/455, Report on Salvage Operations; and Interview: Frank Newman, Engineer Lieutenant RANR, HMS Kanimbla 1939-1942, 2 November 2006.

- ↑ NAA: MP1049/5, Item 2026/3/455, Report on Salvage Operations.

- ↑ NAA: MP1049/5, Item 2026/3/455, Report on Salvage Operations; and Deutsche Dampfschifffahrts - Gesellschaft ‘Hansa’, Kendal, England: World Ship Society, 1967, p. 52.

- ↑ NAA: MP1049/5, Item 2026/3/455, Minutes from Commander-in-Chief, East Indies Station to the Secretary to the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board, 19 November 1941, and to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 18 November 1941; NAA: A6770, Item Humphries, John Thomas; and Gilbert, Australian Naval Personalities, p. 111.

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Sea Power Centre - Australia

Department of Defence

Canberra ACT 2600

seapower.centre@defence.gov.au