The RAN Fleet Air Arm Mark I

The Naval board have decided to establish a Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Australian Navy, based, as far as practicable, on the scheme adopted in the Royal Navy.

And with that order, a Fleet Air Arm (FAA) was established in the RAN. But this was not 1948. This order was promulgated on 16 June 1925.[1]

The decision to create an FAA in the RAN was influenced by developments in the Royal Navy (RN) which had been set in train before World War I (WWI) and, indeed, by the RAN’s own experience with naval aviation in the Great War.

The RN had begun exploring the possibilities of naval aviation as far back as 1909 focussing initially on rigid airships and later, from 1911, on seaplanes and aeroplanes[2]. The naval wing of the British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was established on 13 April 1912, and subsequently became the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) on 1 July 1914. The first purpose-built seaplane carrier, HMS Ark Royal, commissioned in December 1914. The RFC and the RNAS were combined on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. At that time the RNAS comprised an impressive 55,000 personnel, 2900 aircraft, 103 airships and 126 air stations in Britain and overseas.[3]

The RAN’s interest in naval aviation did not lag far behind. In May 1913 naval strategist Commander (later Captain) Walter Thring, RAN, advocated for the acquisition of ‘water-planes’, and the following year the First Naval Member, Rear Admiral Sir William Creswell, RAN, recommended that the 1914-1915 estimates allow for the establishment of an Australian Naval Air Service including 26 personnel and four seaplanes. Without British support, however, which the RNAS was unable to provide, the proposal went no further.

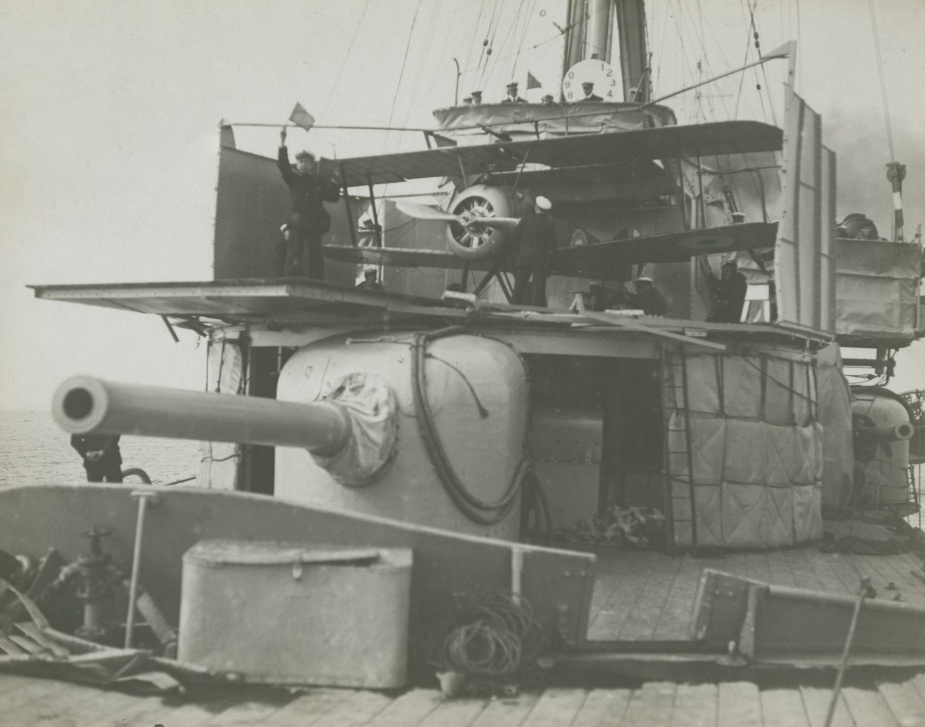

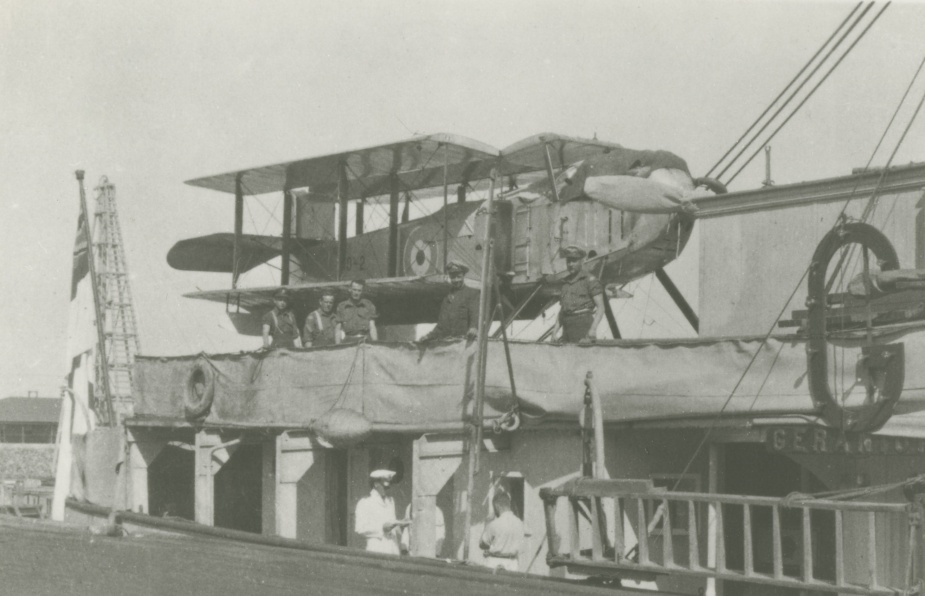

The RN, meanwhile, had commissioned a small number of seaplane carriers. The operational limitations of the carriers and their embarked aircraft, however, led to further experimentation in operating aircraft from cruisers via a makeshift flying-off platform installed atop a gun turret. The RNAS proved to be an attractive option for men seeking to enlist during WWI and more than 200 Australians served in its ranks, at least nine earning the title of ‘Ace’ having shot down five or more enemy aircraft.[4]

While naval aviation was not a decisive influence in the outcome of the war, its potential in both reconnaissance and in offensive operations had become apparent. This was reflected in the rapid growth of naval air services around the world. Great Britain’s service, for example, grew from some 727 personnel in August 1914, to more than 55,000 by April 1918. The United States, whose involvement in WWI was much briefer, saw its service grow from 267 personnel in April 1917 to nearly 40,000 at the Armistice.[5]

The RAF maintained control of naval aviation following its formation in 1918 until 1 April 1924. At that time the Admiralty regained some control as all RAF units embarking in the RN’s new aircraft carriers would come under the operational control of the Navy, and all observers and 70% of pilots were to be naval or marine officers, though pilots would be required to hold additional commissions in the RAF’s Fleet Air Arm.[6] The RN would not regain full administrative control of the FAA until 1937.

The Australian interest in aviation, both on land and at sea, only grew over the course of the war. Naval aviation found a champion in the form of Captain (later Rear Admiral) John Dumaresq, RN, HMAS Sydney’s Australian-born Royal Navy Captain; a man, according to the RAN’s official war historian Arthur Jose, “of exceptional ability and vivid imagination.” Dumaresq was at the forefront of the campaign to develop an embarked aviation capability in the Empire’s cruisers.[7] Dumaresq had designed Sydney’s rotating flying-off platform himself and wrote the Grand Fleet’s first and only instructional manual of the war: Use and Maintenance of Planes Embarked.[8]

The efficacy of offensive embarked operations was demonstrated on 1 June 1918 when Flight Sub Lieutenant Albert Cyril Sharwood, RAF, piloting Sydney’s Sopwith Camel, engaged three German seaplanes during Operation F3. Operation F3 involved some 70 warships and embarked aircraft with the intent of drawing out German forces in Heligoland Bight. The German aircraft attacked the fleet with bombs before being attacked, in turn, by Sharwood. While he did not achieve a kill, Sharwood had initiated the first ever ship-launched, air-to-air interception of an enemy aircraft and was later mentioned in despatches for his actions.[9]

Following the Armistice, both the Navy and Army argued for separate naval and military air branches within their respective existing service structures. Their proposals, however, were derailed by inter-service rivalry. The Australian Government, instead, followed the British model and established a third service. The Australian Air Corps replaced the AFC in January 1920. The Australian Air Force was founded on 31 March 1921 and gained Royal Assent on 13 August.

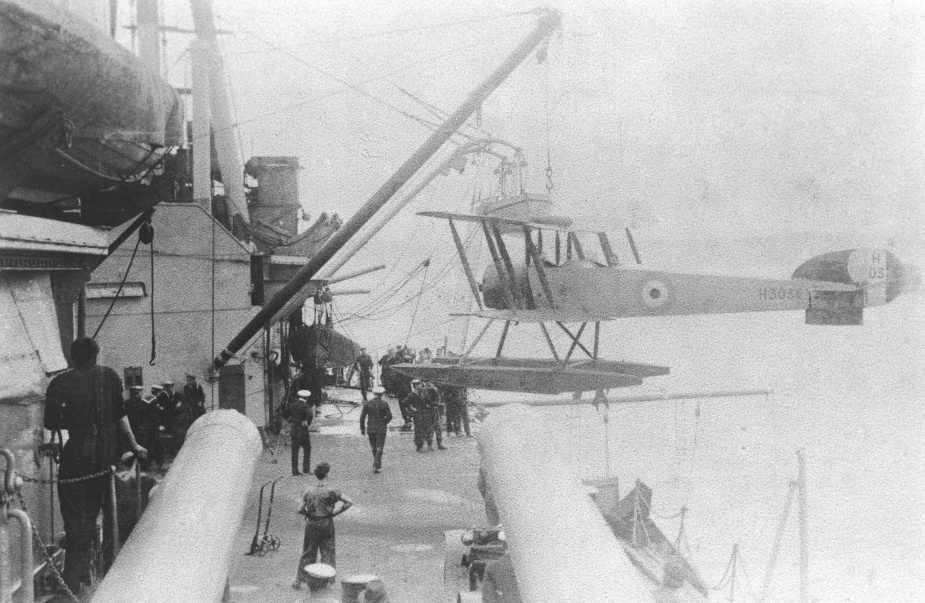

After the unsuccessful deployment of an Avro 504 floatplane and AFC aircrew aboard HMA Ships Australia and Melbourne in 1920, in April 1921 the Government announced its intention to acquire 12 Fairey IIID seaplanes for service with the RAN, a number that was later reduced to six due to financial constraints. The six aircraft arrived in Australia in November 1921 under the operational control of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The aircraft later formed Number 101 Flight (Fleet Cooperation) of the RAAF and, with RAAF aircrew, supported hydrographic operations in Queensland waters and provided fleet support to warships exercising off the NSW coast.[10]

In June 1923 the Naval Board instituted a specialist Observer branch in the RAN and invited volunteers to undergo either short-course or long-course training at RAAF Point Cook on loan to the RAAF. The two-year long-course included pilot training and the trainees were required to wear Air Force uniform upon gaining their pilot’s certificate (after approximately 11 months of training) for the duration of their loan.[11] Without a proper aviation branch in the RAN, however, the long-course proved to be an effective recruiting tool for the RAAF to entice young RAN officers to transfer permanently to the Air Force.

The RAN’s decision to establish an FAA in 1925 was largely borne out of the 1923 Imperial Conference during which it was expressly stated that each portion of the Empire was responsible for its own local defence. While no formal arrangements came out of the conference, the Admiralty did set out its expectations of the RAN’s contribution to the defence of the Empire. This included an aspirational suggestion that Australia acquire four new cruisers, six submarines (ultimately two cruisers and two submarines would be ordered) and seaborne aircraft. It was further suggested that the RAN might take up a merchant vessel capable of carrying aircraft in the event of a war.[12]

The renewed focus on defence and naval aviation enabled the Navy to pursue its aviation ambitions, even in the face of ongoing inter-service rivalry. The two new County Class cruisers, HMA Ships Australia (II) and Canberra (I) respectively, constructed to the tonnage limits of the Washington Treaty, would both be able to carry aircraft launched from a catapult.

The Secretary of the Naval Board, Mr George Macandie, CBE, wrote to his counterpart in the RAAF in June 1924 forwarding him a copy of Admiralty Fleet Order 1058/24 which established the training of RN officers in the RAF FAA. Subsequent discussions between the Naval and Air Boards regarding the establishment of an Australian FAA focussed on personnel matters. When the two boards came to an agreement, the ambiguity in the wording of both the covering minute and the draft naval order establishing the FAA meant that they were at cross-purposes. While the scheme intertwined the two services in a similar manner to the British model, the Air Board interpreted the order as establishing an FAA on the British model, i.e. within the RAAF and under RAAF control, whereas the Naval Board interpreted it as establishing the new branch within the RAN.

Ministerial approval for the establishment of the FAA in the RAN was given in January 1925. The Chief of Air Staff, Group Captain (later Air Marshal Sir) Richard Williams, persuaded the Naval Board to modify the program so that after four years of service pilots would be required to transfer permanently to the either the Air Force or the Navy; however, if they chose the Navy then they would only be able to serve as observers, if they wished to continue their careers as pilots, they would have to choose the Air Force.[13]

Then on 10 June 1925, six days before the order establishing an FAA was promulgated, the Governor-General, Sir Henry Forster, while opening Federal Parliament, announced the Government’s intention construct a seaplane carrier at Cockatoo Island Dockyard.[14] There is a popular misconception that this announcement took everyone, including the Australian Naval Board, by surprise. The truth is that the Government had begun to consider the acquisition of a seaplane carrier the year before.

The decision to acquire the carrier was a political one. The Nationalist Government, led by Prime Minister Stanley Bruce, had been considering acquiring the two new cruisers from British shipyards. This angered the Labor Opposition as it left Australian shipyards, most notably Cockatoo Island, in danger of closure. The seaplane carrier, raised in Cabinet as early as September 1924, was a compromise designed to protect jobs. Consequently, following an enquiry from the Naval Board, the Admiralty provided a rough sketch design for a carrier. When Cabinet met again on 5 March 1925, the decision was made to construct the two cruisers in Britain and to build a seaplane carrier in Australia.[15]

After further, and markedly hasty, correspondence with the Admiralty a design was finalised and the carrier was laid down at Cockatoo Island in April 1926. That December the Naval Board called for volunteers to train as pilots and observers in the FAA stating:

In view of the commissioning during 1928 of a Seaplane Carrier, and the probability that the new Australian Cruisers will carry Aircraft, several Officers are required to commence Air training in 1927.[16]

Meanwhile, wrangling between the Naval and Air boards over control of the FAA continued. Correspondence revolved primarily around the administration of the service with little regard for its operational capability. When capability was raised it referred, in the main, to the carrier; in that regard the RAAF was prepared to provide aircraft and aircrew on the understanding that in the event of battle, the aircraft were to operate as reconnaissance units only.[17]

The Minister for Defence, former Army general Sir Neville Howse, preferred to maintain the status quo; however, Howse was forced to resign the portfolio in April 1927 due to ill health. His successor, another former Army general, Sir William Glasgow, was less supportive of the Navy’s position. The RAN FAA was subsequently disestablished at a meeting of the Federal Cabinet on 18 January 1928.

The seaplane carrier, HMAS Albatross, commissioned on 23 January 1929 under the command of Captain Denham Bedford, RN. Her crew of 450 included 24 RAAF aircrew flying Supermarine Seagull III aircraft. After a brief but active service career, a tightening budget in the midst of the Great Depression saw Albatross paid off into reserve on 26 April 1933 and transferred to the RN in 1938 as part payment for HMAS Hobart (I).[18] The RAAF continued to supply the RAN with aircraft, pilots and maintainers through the 1930s and 1940s flying off the RAN’s cruisers and supporting hydrographic operations.

In spite of this first abortive attempt to establish a Fleet Air Arm in the RAN, the utility of naval air power would be revealed to its full extent in the Pacific theatre in WWII. A second attempt at establishing an FAA would be in train just a couple of years later, and this time with much more success. Though the structure of the service would change over the years, the FAA remains an indispensable part of the RAN.

References

- ↑Commonwealth Navy Order 137/25.

- ↑Stevens, David, In All Respects Ready: Australia’s Navy in World War I, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2014.

- ↑Balance, Theo, The Squadrons and Units of the Fleet Air Arm, Air-Britain Publishing, West Sussex, 2016.

- ↑Stevens, 2014.

- ↑Layman, RD, Naval Aviation in the First World War: Its Impact and Influence, Caxton Editions, London, 2002.

- ↑Balance, 2016.

- ↑Jose, Arthur W, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 Vol. IX: The Royal Australian Navy, Angus and Robertson Ltd., Sydney, 1943.

- ↑Stevens, 2014.

- ↑Stevens, 2014.

- ↑Fairey IIID, Royal Australian Navy, https://seapower.navy.gov.au/aircraft/fairey-iiid.

- ↑Commonwealth Navy Order 214/23.

- ↑Stevens, David (ed.), The Royal Australian Navy, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2001.

- ↑Wilson, David J, The Eagle and the Albatross: Australian Aerial Maritime Operations 1921-1971, UNSW Doctoral Thesis, 2003.

- ↑Sydney Morning Herald 1925, ‘Federal Parliament: Third Session Begins’, 11 June, p.9, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/16218832.

- ↑Wright, Anthony, Australian Carrier Decisions: The Acquisition of HMA Ships Albatross, Sydney and Melbourne, Maritime Studies Program, Department of Defence (Navy), Canberra, 1998.

- ↑Commonwealth Navy Order 401/26.

- ↑Wilson, 2003.

- ↑HMAS Albatross (I), Royal Australian Navy, https://seapower.navy.gov.au/hmas-albatross-i.