The RAN’s Chinese Coastal Steamers

With the onset of World War II in September 1939, the RAN began requisitioning merchant vessels to supplement the fleet and release warships for operational duties around the world. These vessels served as coastal patrol vessels, stores issuing ships, amphibious landing ships, in fact, they were employed in any activity where there was the greatest need. Hundreds of ships and small craft were requisitioned into war service throughout the Commonwealth with many of them retaining their original, often colourful, names. Amongst them were HMA Ships Ping Wo, Poyang, Whang Pu and Yunnan.

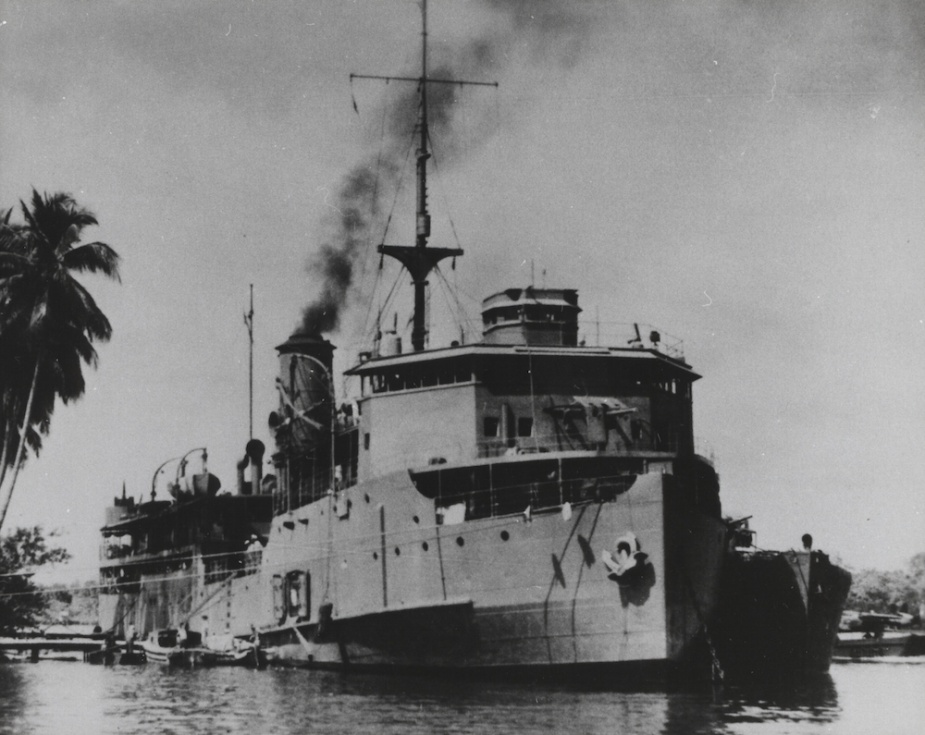

These four ships were coastal streamers owned by Chinese subsidiaries of British shipping companies and were all of a similar size, between 2600 and 3300 tons.

Ping Wo and Whang Pu had both been requisitioned by the RN in 1942 and were in various stages of refit in Singapore when it became apparent that the island would soon fall to the Japanese. On 2 February 1942 they joined a large number of Allied warships and merchant vessels which were evacuating the port up until the final surrender of the island on 15 February.

The two ships made their way to the Australian west coast with Ping Wo enduring the more eventful passage as she participated in the longest continual tow in Australian naval history. HMAS Vendetta was undergoing a refit in Singapore in 1942 and could not be made seaworthy in time to escape the Japanese advance. With only a skeleton crew onboard, the decision was made to tow Vendetta from Singapore to Melbourne, a journey of some 8000km that took 72 days. Ping Wo was one of five ships involved and handled the tow from Batavia to King George Sound from 17 February to 24 March. With doubts about the seaworthiness of Ping Wo in the rough waters of the Great Australian Bight, the tow was handed over to the smaller but more sturdy SS Islander. Ping Wo remained in company with Vendetta and Islander for a time as she continued on to Melbourne and, indeed, nearly fell victim to the waters of the Bight. Vendetta’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant WG Whitting noted at one point “Ping Wo has completely disappeared. We last saw her running before the gale like a surfboard.”[1] But Ping Wo did make it across the Bight, and commissioned as HMAS Ping Wo on 22 May 1942.

Whang Pu, meanwhile, arrived safely in Fremantle on 1 March. She had been fitting out as a submarine depot ship for the RN before the fall of Singapore, and spent the next year and a half at Fremantle as an accommodation ship for Dutch submarine and minesweeper crews as the Australian and British naval authorities considered how best to use her.

Poyang and Yunnan did not have to escape the oncoming Japanese in Singapore as they were already in Australian waters. Poyang had arrived in Broome from southern China on 19 December 1941 while Yunnan had arrived in Fremantle from Singapore on 23 December. Both were requisitioned by the RAN in February 1942 and fitted out as Armoured Stores Issuing Ships in Melbourne before heading to Sydney at the end of April. The two ships operated primarily off the Australian east coast for the remainder of 1942 and most of 1943 making occasional voyages to New Caledonia and New Guinea.

By mid-1942, all four ships were being used by the RAN in some capacity, but Ping Wo was the only one that had been commissioned into the RAN. After fitting out in Melbourne, Ping Wo departed for Sydney in June. In September she continued on to Port Stephens to operate as a support vessel to the Combined Operations Training Centre, HMAS Assault. She was used primarily to transport water and other stores to the Landing Ships Infantry but was also used as a training ship. Some 20,000 Americans and 2000 Australians received training in amphibious warfare at Assault over two years. When the Centre was closed down in October 1943, Ping Wo was converted to a repair ship and redeployed to New Guinea.

Ping Wo remained in New Guinea throughout 1944, based mainly at Milne Bay, conducting the unglamorous but essential work of a repair vessel and fulfilling other duties as required. In January 1945 she returned to Melbourne to refit as a works ship to carry out naval construction work at ports where civilian labour was not available. She was underway again that July bound for Morotai in the Moluccas with a directive in force that neither the crew nor the ship’s equipment was to be disintegrated in any way without the prior approval of the Naval Board.[2] Such was the parlous state of naval bases in the Pacific that officers at Torokina and Rabaul made enquiries as to the availability of Ping Wo to assist in construction efforts there before the ship had even left Australian waters. As it happened, Ping Wo experienced engine difficulties and was delayed at Townsville, preventing her from reaching any of those destinations. She instead made for Madang in October where she once again acted a stores issuing ship until February 1946, assisting in the repatriation of Allied servicemen and former prisoners of war. She then sailed for Hong Kong where she arrived on 8 June 1946, decommissioned on 24 June and was subsequently returned to her owners.