HMAS Sydney (I) - Part 2

| Class |

Town Class |

|---|---|

| Type |

Light Cruiser |

| Builder |

London and Glasgow Engineering Co, Govan, Glasgow, Scotland |

| Launched |

29 August 1912 |

| Launched by |

Lady Henderson, wife of Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson |

| Commissioned |

26 June 1913 |

| Decommissioned |

8 May 1928 |

| Dimensions & Displacement | |

| Displacement | 5400 tons |

| Length | 456 feet 10 inches |

| Beam | 49 feet 10 inches |

| Draught | 15 feet 9 inches |

| Performance | |

| Speed | 26 knots |

| Complement | |

| Crew | 376 |

| Armament | |

| Guns | 8 x 6-inch guns, 1 x 13-pounder gun, 4 x 3-pounder guns |

| Torpedoes | 2 torpedo tubes |

| Awards | |

| Battle Honours | |

In Emden, Von Müller immediately recalled his landing party, raised steam and cleared his ship for action. Unable to wait any longer for the return of his shore party he weighed anchor and cleared the harbour to the north-north-west to try and improve his position with the intention of inflicting as much damage on Sydney (I) as possible in the opening stages of the inevitable engagement. Emden opened fire at a range of 10,500 yards using the then very high elevation of thirty degrees. Her first salvo was 'ranged along an extended line but every shot fell within two hundred yards of Sydney (I)'. The next salvo was on target and for the next ten minutes the Australian cruiser came under heavy, accurate fire. Fifteen hits were recorded but fortunately only five burst. It was during the opening stage of the engagement that Sydney (I) sustained all of her casualties. Two shells from a closely-bunched salvo hit the after-control platform wounding all of the personnel closed up there, while a direct hit on the upper bridge range finder took off the operator's leg putting the equipment out of action.

Sydney’s first salvo went ‘far over the Emden’. The second fell short and the third scored two hits. Meanwhile, Von Müller, aware that his only chance lay in putting Sydney (I) out of action quickly, maintained a high rate of fire, reported to be a salvo every six seconds. It was to no avail. In spite of the damage to her range-finders Sydney (I) used her superior speed and fire power and raked the German cruiser.

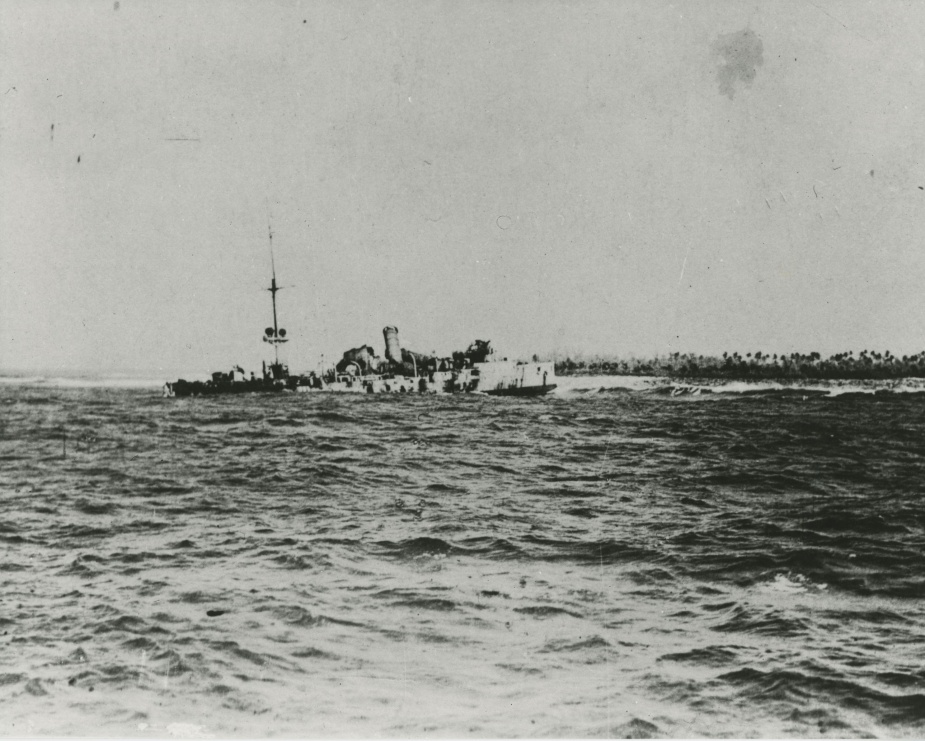

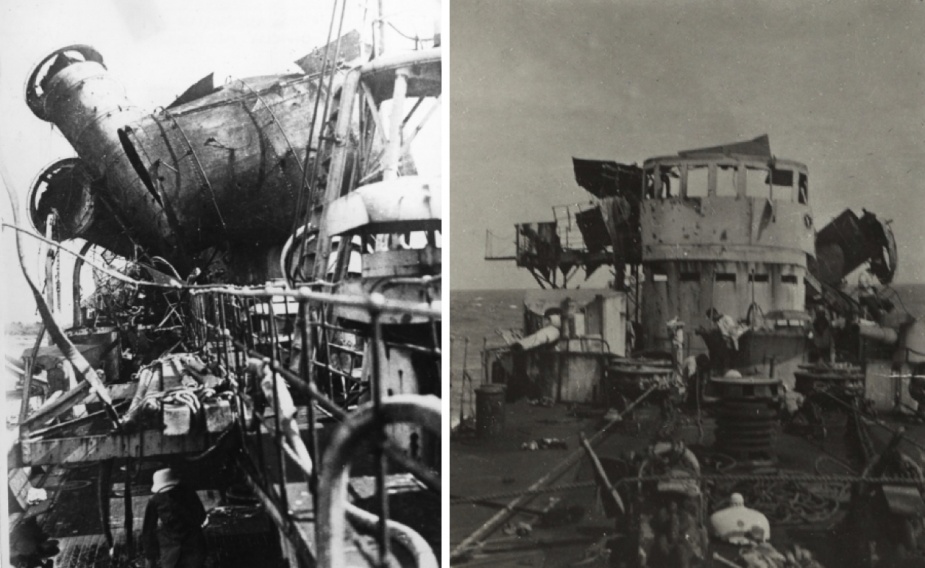

Her shells wrecked the enemy's steering gear, shot away both range-finders and smashed the voice pipes, severing communications between the conning tower and the guns. Shortly afterwards, Emden's forward funnel toppled overboard followed by the foremast which carried away the primary fire control station and wrecked the fire bridge. Despite the damage and the inexorable end, Von Müller continued the engagement. Half his crew was disabled until "only the Artillery Officer and a few unskilled chaps were still firing". Finally, with his engine room on fire and with a second funnel gone, he gave the order "to the island with every ounce you can get out of the engines". Shortly after 11:00, Emden was seen to be fast on the North Keeling Island Reef.

When Glossop saw that his opponent was aground and incapable of movement, he left her in order to pursue the Buresk, which during the action had hovered in the vicinity to the north. Overtaking the vessel shortly after noon, he fired a shot across her bows to stop her and sent an armed boarding party across to secure her as a prize. Her German crew, however, had opened and then damaged the sea cocks to prevent her capture and she was already sinking. The boarding party and German crew were consequently recovered and four shots were fired into Bureskby Sydney(I) to speed her on her way to the bottom.

Glossop’s attention now returned to Emden which he reached at approximately 16:00. On nearing her it was observed that she was still flying the German ensign at the mainmast. A signal was made to her by flag hoist “Do you surrender”. The Emden made back by Morse flags (wig wag) “no signal books, what signal”. Sydney (I) responded, using Morse flags, with “Do you surrender” followed shortly afterwards by “Will you surrender”. No reply was received from Emden and the order was given to “open fire, aim for the foot of the mainmast”. Several salvoes were fired when a man was seen to be climbing aloft in Emden. Glossop ordered his gun crews to ‘cease fire’ and the German ensign was subsequently seen to be hauled down and a white flag waved as a token of surrender. The Imperial ensign was subsequently destroyed by the Germans as soon as it was hauled down.

Once Emden had surrendered, Glossop dispatched a boat manned by some of the seamen from the Buresk with water and a letter to be delivered to Captain Von Müller. Glossop’s letter read:

I have the honour to request in the name of humanity that you now surrender your ship to me. To show how much I respect your gallantry, I will recapitulate the position. You are ashore, three funnels and one mast down and most guns disabled. You cannot leave this island and my ship is intact. In the event of you surrendering, in which I venture to remind you is no disgrace but rather your misfortune, I will endeavour to do all I can for your sick and wounded and take them to a hospital.

With night approaching, Sydney (I) departed the area and sped towards Direction Island to try and capture Emden’s landing party. They arrived too late, learning that Von Mücke, having witnessed Emden’s destruction from the shore, had commandeered the schooner Ayesha and made good his escape. He, together with his landing party, eventually made it safely back to Germany following an epic journey over sea and land.

Sydney (I) returned to the aground Emden the following morning where the situation onboard the crippled raider was desperate. Men were lying killed and mutilated in heaps. The ship was riddled with gaping holes, and had been gutted by fire. Emden’s chief surgeon, Dr Luther, had done what he could for the wounded during the preceding night whom he had attended unassisted and with only a scant supply of dressings and appliances. Under difficult circumstances Sydney’s crew took on some 190 German survivors during a transfer that lasted five hours. The wounded, many of them seriously, were attended devotedly by Sydney’s young surgeon lieutenants (L Darby and ACR Todd) and medical staff who, assisted by Dr HS Ollerhead from Direction Island, worked for forty hours without sleep to ease their suffering. Sydney (I), then heading for Colombo, rendezvoused with the auxiliary cruiser Empress of Russia on 12 November 1914 and all prisoners who could be moved were transferred to her. On 15 November 1914 Sydney (I) arrived in Colombo from where she later proceeded to Malta where she arrived on 3 December.

From Malta she was ordered to Bermuda to join the North America and West Indies Stations for patrol duties. For the next eighteen months Sydney (I) was engaged in surveillance duties off neutral ports in the Americas.

On 9 September 1916 Sydney (I) finally left Bermuda, arriving at Devonport on 19 September before proceeding to Greenock for refit. On 31 October 1916 she was temporarily attached to the 5th Battle Squadron at Scapa Flow. On 15 November she sailed for Rosyth and on arrival joined her sister ships HMS Southampton, HMS Dublin and HMAS Melbourne as part of the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, attached to the 2nd Battle Squadron of which HMAS Australia was the flagship. For the remainder of the war her service was confined to North Sea patrols.

On 4 May 1917, while on patrol from the Humber estuary to the mouth of the Firth, Sydney (I) fought a running engagement with the German Zeppelin (airship) L43 until Sydney (I) had expended all the anti-aircraft ammunition and the L43 all her bombs - ‘the combatants parted on good terms’. A number of small bomb splinters landed on Sydney’s upper deck.

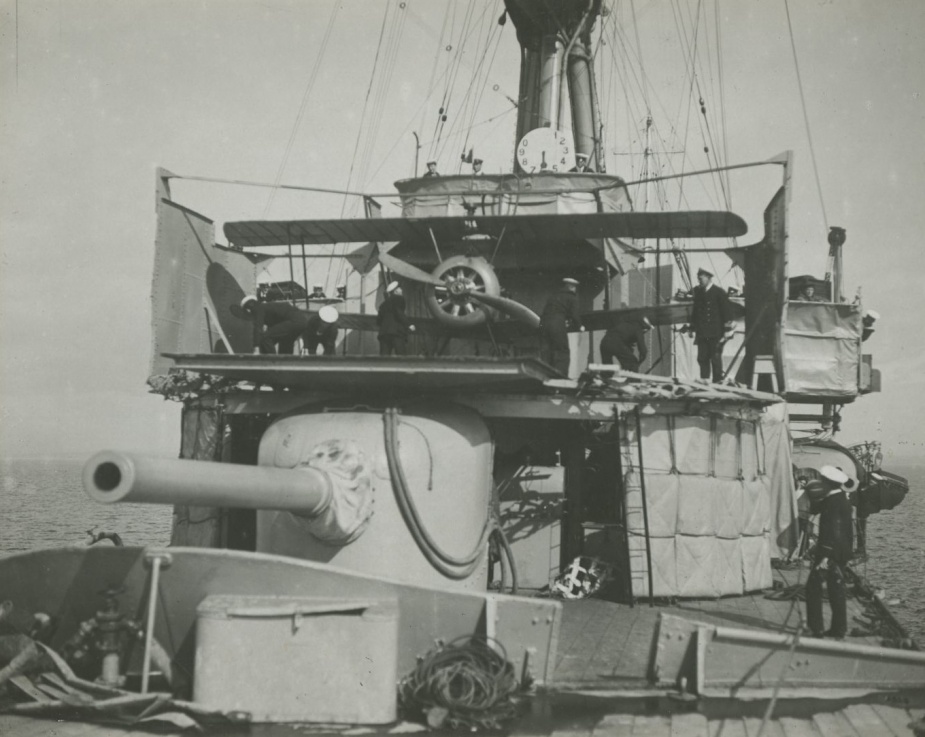

Later, in August 1917 Sydney (I) commenced a three month refit at Chatham, during which the tripod mast now situated as a memorial at Bradleys Head, Sydney, NSW was fitted to her. Of more significance however, she was fitted with the first revolving aircraft launching platform to be installed in a warship.

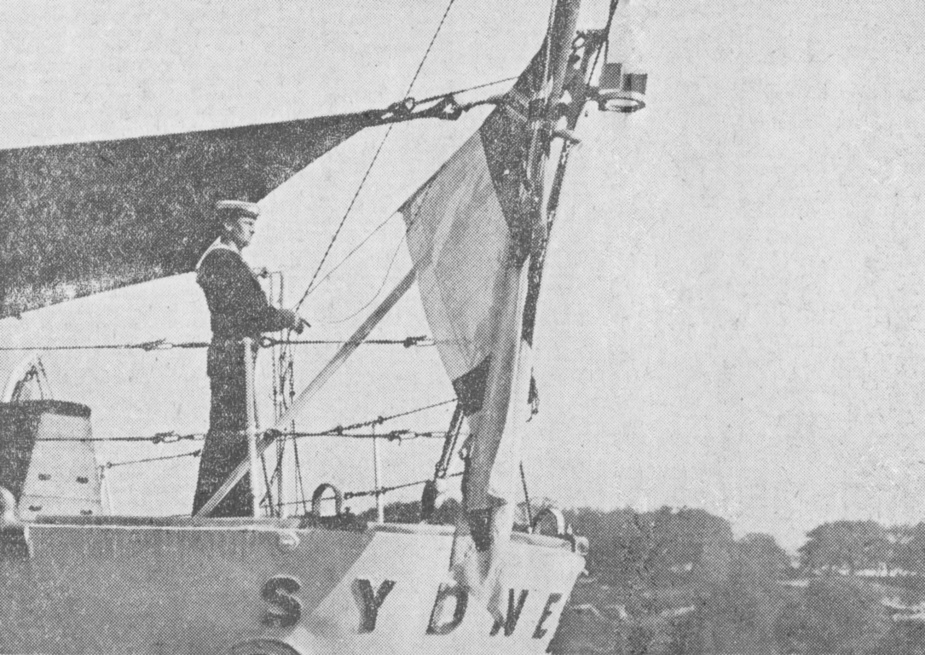

On arrival at Scapa Flow in December 1917, her Commanding Officer Captain Dumaresq, borrowed a Sopwith Pup then being operated from a fixed platform on the cruiser Dublin for use onboard Sydney (I). On 8 December 1917 the aircraft was launched successfully from Sydney's platform in the fixed position. It was the first aircraft to take off from an Australian warship. Nine days later the Pup flew off the platform turned into the wind; the first time any aircraft had been launched from such a platform in the revolved position. Early in 1918 Sydney (I) took on board a Sopwith Camel, the standard fighter plane which superseded the Sopwith Pup.

On 1 June 1918 as the Royal Navy force to which Sydney (I) was attached entered enemy controlled waters, two German seaplanes were sighted by Sydney (I) at 09:33 diving towards HMAS Melbourne. Both aircraft dropped bombs but no hits were scored. Lieutenant AC Sharwood, RAF was quickly strapped into the cockpit of Sydney’s Sopwith 2-F1 Camel, N 6783, and turned into the mean wind 20 degrees off the centerline of the ship. The launching party comprised his engine fitter Birch; rigger Radcliffe and joiner/mechanic Graffy under the direction of Sydney's First Lieutenant, Lieutenant Commander Garsia, RAN. Sharwood was launched at 09:55 and Melbourne's Camel, N 6756, piloted by Flight Lieutenant LB Gibson was launched at 10:00. Gibson climbed into cloud but failed to locate the enemy aircraft. He returned to circle the force and played no further part in the subsequent air action. This led the captains of HM Ships Courageous and Glorious to think that the enemy had been driven off and consequently they did not launch their aircraft.

Sharwood, meanwhile, had climbed to 10,000 feet and pursued the German aircraft for 60 miles before he was able to engage, diving onto one of the aircraft and firing bursts into it. Official accounts mention only the two seaplanes but Sharwood's Log Book recalls “Flight from Sydney (I) after three Hun Sea planes (two 2 seaters and one 1 seater)”. Evidently it was the single-seater which he had hit, observing it shudder before diving into the sea. As he followed it down he was ‘bounced’ by another German aircraft, which he engaged before breaking off the attack when his guns jammed. He was now faced with the dilemma of returning safely to Sydney (I) which by now was over 70 miles away. By luck he saw the Harwich Force destroyer HMS Sharpshooter below him and ditched alongside it, where he was rescued by sea boat. The cruiser HMS Canterbury later recovered the aircraft.

Sharwood's claim of one enemy seaplane forced down was not recognised by the Admiralty because there was no independent corroboration and his gallantry was never rewarded but the interception confirmed Dumaresq's faith in the future of aircraft.

Sydney (I) was present at the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow on 21 November 1918 and was again involved with a German ship carrying the name Emden when she escorted her old enemy’s namesake into Scapa Flow for internment. Sydney (I) sailed from Portsmouth on 9 April 1919 for the return passage to Australia calling at Gibaltar, Malta, Port Said, Port Suez, Aden, Colombo, Singapore, Penang, and Thursday Island before arriving in her home port of Sydney on 18 July 1919. Sydney (I) had come the long way home and her arrival passed almost unnoticed until the following morning when passengers on the Sydney ferries became aware of her presence at her buoy. The return was an anti-climax, but for her crew, many of whom had last seen the port almost four years ago, the thrill of being home was an ample reward.

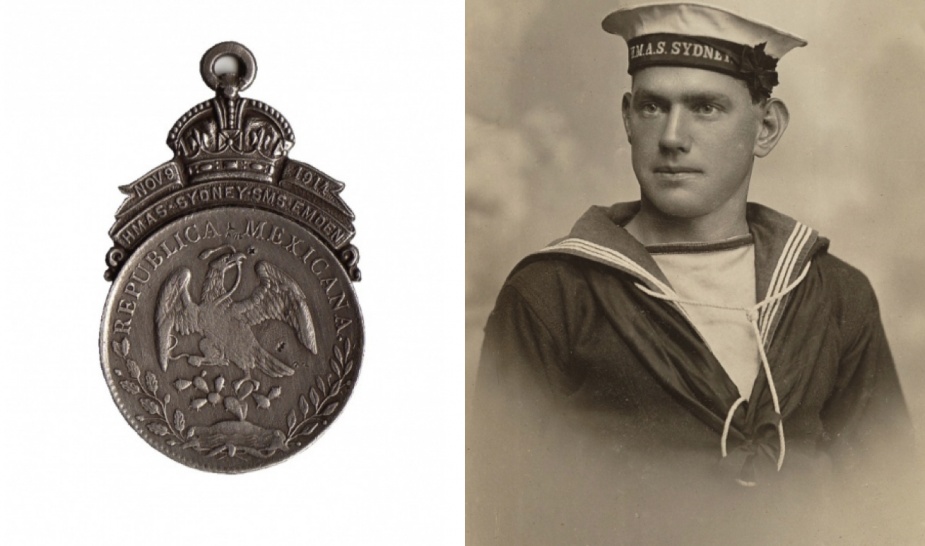

In 1918 a commemorative medallion was struck by the Navy to recognise Australia’s first naval fight. The centrepiece for this medallion consisted of a Mexican silver dollar, of which some 6429 were recovered from the wreck of Emden. The coins were mounted by the Sydney jeweller W Kerr and presented by Captain Glossop to the officers and men of Sydney (I) who were on board at the time of the engagement. Others were given to the staff on Cocos Island as well as the Admiralty, the Australian War Memorial and other approved museums. The remainder was sold to the public. Of the remaining unmounted coins, 653 were distributed by the Department of Navy, 343 were sold to the public and 4433 were melted down and the money used by the RAN Relief Fund.

Another medal was commissioned on behalf of the citizens of Western Australia to specifically recognise the part played in the battle by officers and sailors in Sydney (I) who came from Western Australia. This medal was cast in silver by JC Taylor’s Jewellery Works of Perth and depicted an engraving of Sydney (I) with the words “To Commemorate the Victory Over the Emden” above it.

Sydney operated mainly in Australian and South West Pacific waters for the remainder of her career. In December 1919 she was in the Timor Sea and on standby to render assistance, if needed, to Keith and Ross Smith who were flying a Vickers Vimy bomber to Australia on the first England-Australia flight. The cruiser took part in the Royal Visit by HRH The Prince of Wales to Australia in June 1920.

In 1922 she conducted a showing the flag cruise to the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) and New Caledonia before being placed in reserve on 13 April 1923. Sydney was recommissioned on 29 November 1924 as the flagship of the RAN and conducted exercises off the east coast of Australia.

In early February 1925 she embarked the First Naval Member, Rear Admiral Percival Hall, CB, CMG, RN and his staff for passage to Singapore for the Pacific and Far East Conference. In the days before commercial air travel RAN warships were often used to move senior officers to overseas meetings and to remote areas. After returning to Australia she resumed her normal peacetime exercise program including the traditional visit to Victoria during the Melbourne Cup period. Sydney visited Auckland and Wellington in New Zealand, during March 1926, for exercises with the New Zealand Squadron of the Royal Navy before a cruise to the southern states during August-November.

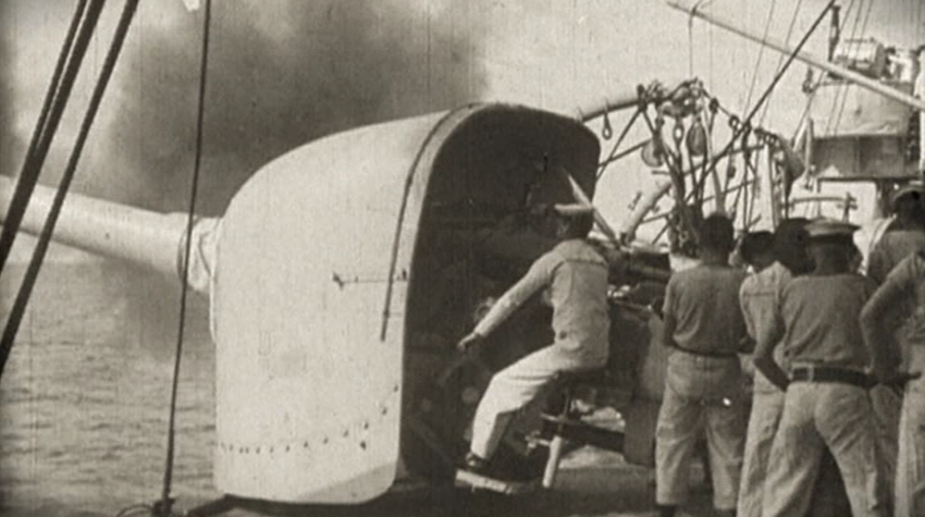

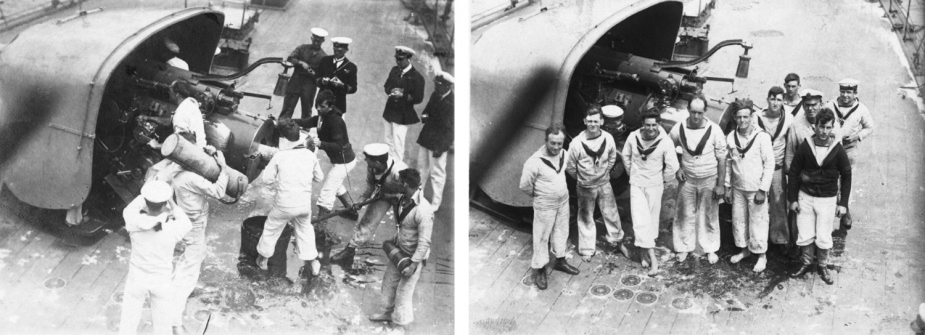

1927 saw the cruiser undertake a circumnavigation of Australia and a port visit to Dili, in Portuguese Timor, in June. She also visited the South West Pacific during September-October for a showing the flag cruise with port visits to Noumea (New Caledonia), the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. In March 1928 Sydney became a movie star when she was used as the site for Ken Hall's cinesound movie ‘The Exploits of the Emden’. The film was shot on board Sydney off the east coast of Australia using her crew as both Australian and German sailors. The ‘Cocos Island’ shore scenes were filmed at Jervis Bay using the cruisers crew as the landing party.

Sydney paid off at Sydney on 8 May 1928, and on 10 January 1929 was delivered to Cockatoo Island for breaking up. Sydney’s stern and several other artifacts including guns from her main armament were donated to the Australian War Memorial and a number of other museums and naval bases around Australia.

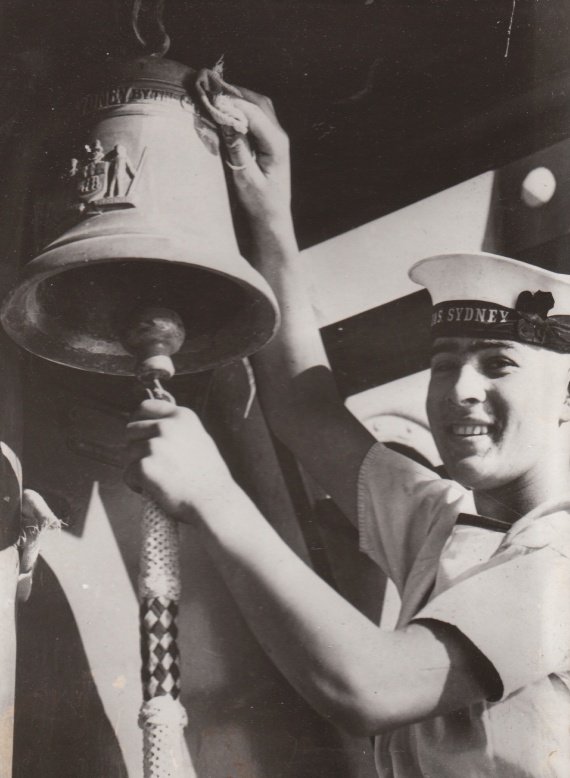

HMAS Sydney’s ship’s bells

HMAS Sydney (I) carried two ships bells. One which commemorated the ship's commissioning in 1911 and another that was presented to the ship on her arrival in her namesake port in 1913. The second bell was of solid silver weighing approximately 1000oz. It bore a representation of the City of Sydney Coat-of-Arms and the words “Presented by the citizens of Sydney to HMAS Sydney”. Both the coat-of-arms and the lettering were hand carved. When HMAS Sydney (II) arrived in Australia the bell was transferred to her in a continuation of the tradition. Regrettably the bell was lost when HMAS Sydney (II) was sunk on 19 November 1941 following a fierce engagement with the German raider HSK Kormoran.

Commanding Officers of HMAS Sydney (I)

| 26 June 1913 | Captain JCT Glossop, RN |

| 5 February 1917 | Captain JS Dumaresq, CB MVO RN |

| 1 August 1919 | Captain HP Cayley, RAN |

| 3 November 1922 | Captain SR Miller, RN |

| 13 April 1923 | Paid off into Reserve |

| 29 September 1924 | Recommissioned |

| 29 September 1924 | Captain CFS Danby, RN |

| 25 April 1925 | Captain H Boyes, CMG RN |

| 26 July 1926 | Captain FHW Goolden, RN |

| 15 October 1927 | Captain GL Massey, RN |

Song of HMAS Sydney

Three long black lines of troopships, from Albany they steer

The ‘Melbourne’ proudly at the head, the ‘Sydney’ at the rear

The answer to old England’s call, the flower of her Southern sons,

When hark! there comes a call for help, tho blurred by the Huns.

The ‘Melbourne’ was the flagship, and dare not leave her place,

So off the ‘Sydney’ streaked full speed, nigh thirty knots her pace;

They guessed ‘twould be the Emden’, and o’ver the foam they sped,

To catch the raider at her work, now sixty miles ahead.

The stokers worked like demons, and soon the Germans saw

Smoke plumes and a mighty bow wave, Von Müller dropped his jaw.

Then he laughed, “If that’s a cruiser, on the skyline which I see

It can’t remain one very long, for ’twill be sunk by me.”Chorus

But then he had to reckon with Australia,

He didn’t know the dinkum Aussie Jacks,

But he met them by the Cocos,

And he got some broken bones,

And that what comes of boasting near AustraliaAnd now the 'Sydney' checked her speed, and onward came the foe,

The lads stood calm beside their guns, with hearts and eyes aglow;

The youngest Navy in the world, was out to win her spurs.

And men would fight and men would die, and glory would be hers!

And there they fought a valiant fight, and there they stoushed the Hun;

They plugged the pirate raider till she hadn’t an answering gun;

And when the proud Von Müller had skied the flag of white,

Brave Glossop shook him by the hand, for ‘twas a good straight fight.He made him a guest of honour, and gave him back his sword.

Then they took the captives with them, tending their wounded aboard

And back to join the convoy, the ‘Sydney’ steamed away,

On the Southern seas the pirate Hun, had seen his long day.Chorus

Because he had to reckon with Australia,

He didn't know the dinkum Aussie Tars,

But he met them on the ocean,

And now he has a notion

And that what comes of boasting near AustraliaIn fair Colombo harbour, that wonderful array,

Of forty great black transports, swarming with soldiers lay;

Waiting to greet the conqueror, with pent emotion thrilled

The ships hung gay with bunting, but never a whistle shrilled.

Thru’ lines of towering troopships, the little ‘Sydney’ steered

Beneath those stalwart khaki throngs, and never a soldier cheered.

With hat in hand and silent, they watched her steaming by

In young ‘Australia’s crowning hour, the bewildered Huns gasped “Why?”

As there were wounded prisoners aboard, they came to learn -

No noisy demonstration must mark the ships return.

“You have been kind, but this crowns all” Von Müller tried to speak,

“We cannot hope to thank you.” The tears streamed down his cheek.Chorus

But then he had to reckon with Australia,

He didn't know the dinkum ‘Ginger Micks’,

But now he's getting wise,

And the tears that filled his eyes

Are not the least of tributes to AustraliaBy EMC Durban