HMAS Melville

HMAS Melville was a commissioned shore establishment located in Darwin. It was named after Melville Island (Yermalner), part of the Tiwi Islands group, situated on the northern coast of Darwin.[1] Melville’s motto was “Essayez”, meaning “to try”.

The naval presence in Darwin dates back to 1911 with the establishment of a Naval Reserve Sub-district depot. The Darwin naval reserve depot had a modest staff comprising a Lieutenant, one Chief Petty Officer instructor and one boatman. During the First World War, Darwin was used as a coaling station by naval vessels. No longer required, the Darwin naval reserve depot was closed down in September 1922.[2]

New naval works at Darwin

During the 1930s, there was a growing awareness within defence circles of the strategic value of Darwin. Much of the decade saw the Naval Board debating the Navy’s presence in Darwin, with cost being the main obstacle. In January 1935, a naval reserve depot was re-established in Darwin under the command of Lieutenant Commander Herbert P Jarrett, RAN, as part of the Naval Reserve District of Queensland.

A commitment to a more substantial naval presence in Darwin came in August 1936, following an Imperial Communications Report on the Subject of Wireless Stations in Australia for Defence Purposes. The report recommended new works in Darwin and Canberra. The new works consisted of a naval direction finding station and short wave wireless telegraphy (W/T) station consisting of a 500 watt wireless transmitter and receiver and a 25 watt wireless transmitter and receiver. The port was also equipped with visual signalling apparatus. With a daytime range of 2000 miles, these new W/T works would ensure reliable duplex communications reaching as far as the Royal Navy’s Singapore Naval Base.[3]

The decision to act on the recommendations of the Imperial Communications Report was underpinned by a keen appreciation of geopolitical upheaval and the protection of the arc of islands to Australia’s north. The Naval Board Secretary remarked that, “in view of the international situation, it is desired to urge that favourable consideration may be given to the construction of Canberra and Darwin stations being undertaken as early as possible”.[4]

In 1937, following a survey of Darwin carried out by HMAS Moresby, the Coonawarra area was selected as the main site for new naval works, including the W/T station. The W/T station, becoming operational on 18 September 1939.[5] In 1937, while construction was underway in Darwin, the Naval District of the Northern Territory was separated from the Queensland District. Lieutenant Commander Alexander Fowler, RAN, became the first District Naval Officer in Darwin and was succeeded in 1938 by Lieutenant Commander Jefferson H Walker, RAN. These men oversaw the construction of a Naval Headquarters, residences, and berthing and workshop facilities. Strategic stores were also built, including an immense oil fuel installation and naval armament storage.[6]

Upon the outbreak of the Second World War, the Darwin establishment was commissioned as HMAS Penguin (V). This name was short-lived as the existence of multiple shore establishments named Penguin caused some confusion and it was decided that each establishment would have its own distinct name. Penguin (V) was subsequently commissioned as HMAS Melville on 1 August 1940.[7]

Darwin during wartime

As was the case for much of Australia, the effects of the war were initially slow to reach Darwin. Lieutenant Commander Walker - who would later captain and go down with HMAS Parramatta when she was torpedoed and sunk on 27 November 1941 - initially had no ships under his command. One amusing recollection of Christmas 1939 tells of Walker, a popular and jovial man, and his staff commandeering pushbike ‘destroyers’ then sailing the flotilla through the streets of Darwin.[8]

One of the more unusual challenges Melville faced during the early months of the war was flies. The hot and humid climate combined with the rapid influx of personnel - and the waste they invariably produced - led to a fly infestation in Darwin. The Medical Sub-Committee of the Darwin Defence Co-ordination Committee deemed the flies “a serious menace to public health and consequently to the well-being of Services personnel.” The solution was the provision of additional infrastructure such as rubbish incinerators, depriving the flies of their breeding grounds.[9]

Along with these more unusual goings-on, the early months of the war saw personnel stationed at Melville completing trade and local defence exercises to test the Navy’s capability and preparedness in the event of an attack. These exercises generally drew on combined forces with the coastal batteries engaged, the W/T station providing communication and RAAF aircraft providing air support.[10]

The first-half of 1940 was near cataclysmic for the Allies: Germany swiftly conquered Denmark, Norway and the Low Countries throughout April and May; Italy declared war on the Allies on 10 June; a week later France sought an armistice. This series of Allied capitulations had ramifications beyond Europe, sparking fears that Japan would capitalise on the Allies’ vulnerable position in the Asia-Pacific. In May, the British government requested urgent help in Pacific defence, asking that Australia make available additional sloops, armed merchant cruisers and aircraft.[11]

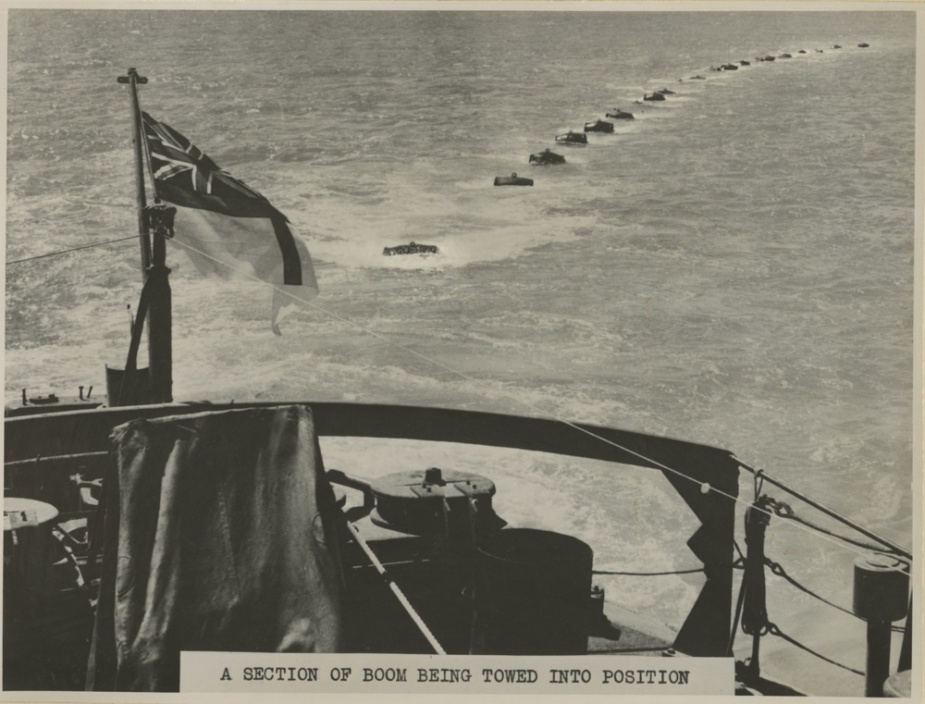

As the remit of Australian contributions expanded and concerns about home defence grew, approval was sought and granted for the installation of three alarm sirens at Melville. These were “urgently required to facilitate the assembly of Defence personnel in an emergency, and for warning the civilian population.”[12] The sirens would prove valuable following Japan’s entrance into the war, when Darwin became a target for enemy air attacks. Plans were also approved for fixed harbour defences, consisting of an anti-submarine boom net between West Point and Dudley Point, and indicator loops laid approximately 8 kilometres to seaward of the boom. The boom laying was initially scheduled to be completed in late 1940, however, the significant preparations required delayed construction. Construction began in October 1940, with crew from boom defence vessels HMA Ships Koala, Kookaburra and Kangaroo delivering equipment and assisting in the driving of concrete piles and boom laying - and was completed in February 1942.[13]

Japan entered the Second World War on 7 December 1941 with the dramatic attack on the US Naval Station Pearl Harbor and other locations in East Asia. Upon Japan’s entrance into the war, four Darwin-based Japanese owned luggers Mars, Mavie, Medic and Plover were seized and requisitioned into the RAN.[14]

Melville served as an intermediate base for Australian and American personnel, aircraft and ships that were destined to travel north to the Netherlands East Indies. Along with considerable fuel reserves, this rendered Darwin among Australia’s most strategically valuable points. The effect of the Pacific War was, accordingly, felt very suddenly in Darwin. A lighting policy was introduced on 12 December, with street lights extinguished and building lights reduced by half. On 14 December, under strict instruction from Prime Minister Robert Menzies’ War Cabinet, women and children were ordered to evacuate.[15] The first of these evacuations were by sea, with SS Zealandia and MV Koolinda transferring around 900 and 300 evacuees respectively on 20 December. USS President Grant transferred a further 225 women and children on 23 December. The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) provided vital air cover for these vessels.[16]

Arguably the most dramatic moment in Darwin’s wartime experience came on 19 February 1942 when, just before 1000, Japanese aircraft attacked the city. 54 heavy bombers, 27 dive bombers and 18 zero fighters attacked shipping and harbour facilities, and the RAAF aerodrome. At 1210, a second attack was made on the RAAF aerodrome. Anti-aircraft batteries returned fire and soldiers even fired their machine guns at the attacking aircraft. One of the Zeros crash-landed on Melville Island where Tiwi man Matthias Ulungura captured the pilot PO Hajime Toyoshima. Ulungura delivered his prisoner to the RAAF radar station on nearby Bathurst Island, making Toyoshima the first Japanese POW to be captured on Australian soil.[17]

Over the course of the two attacks on 19 February, 243 people were killed and a further 400 wounded. Of the total 45 vessels in the harbour, eight were sunk, one beached and subsequently lost, and 11 were damaged.[18] This was the first and largest single air raid ever mounted against Australia. By the end of the war, more than 60 attacks were launched on towns across northern Australia.

In the weeks following the raid, the Naval Officer in Charge, Darwin, Commodore CJ Pope, RAN, reported anxiety and low morale among personnel: “The first raid was of course sudden and very severe on the harbour and waterfront and it was perhaps a hard test on many men who had never really seen war in any form to meet it suddenly and unexpectedly in that way”.

Following the first raid, Darwin’s Administrator ordered a complete civilian evacuation. The only remaining civilians were employees of the Public Works Department as they provided necessary support to defence personnel stationed in Darwin.[19] There were many more enemy attacks on Darwin during the course of the war, and sirens and black-out were a regular occurrence.

Enemy minelaying and scores of air attacks on merchant shipping and allied vessels occurred in the waters off Darwin. The 24th Mine Sweeping Flotilla and patrol vessels stationed at Melville were accordingly kept busy with escort duties, minesweeping and search and rescue operations. One of the more daring episodes involved the requisitioned auxiliary minesweeper HMAS Patricia Cam. Early on the morning of 13 January 1943, Patricia Cam departed Melville with stores and personnel for outlying stations. On 22 January, she was on course for Wessel Island when she was bombed and ultimately sunk by a Japanese air attack. Nine of the 25 on board died during the attack or from injuries sustained, including three Indigenous passengers. The ship’s life raft remained intact and the remaining 18 survivors used makeshift oars to row to a small unnamed islet, arriving early on the morning of 23 January. Two of the survivors perished as a result of their injuries and were buried on the beach. On the morning of 25 January, an Indigenous search party, having received news of the attack, arrived by canoe. They escorted Patricia Cam CO Lieutenant AC Meldrum, RANR(S), to seek aid at the Coastwatching Station on Marchinbar Island. By the time of Meldrum’s arrival, Australia’s armed forces were already aware of the marooned survivors of the Patricia Cam. A RAAF Beaufort bomber had sighted the survivors on the beach and an SOS message scrawled in the sand: “PATCAM - Bombed - No Food - Plenty Water”. The survivors were rescued by HMAS Kuru on 29 January, returning safely to Darwin two days later.[20]

Cessation of hostilities

On 25 August 1945, Melville received news that “the Commonwealth Government was most anxious that Australian forces should receive the surrender of the Japanese garrison in Timor and occupy the Island as soon as possible after the formal surrender of Japan.” Australia’s anxiousness to be directly involved in the surrender stemmed from fears that the great powers would overlook Australia’s contribution to the war effort and its interests in the peace negotiations.[21] The RAN’s involvement in the surrender acted as a tangible demonstration of Australia’s contribution to the war effort, staking a claim in the peace negotiations.

The RAN personnel in Darwin readied themselves “to move at the moment the order for commencement of operation was given”. This operation, known as Operation TOFO, was the final act of war in northern Australia. On the morning of 7 September Operation TOFO commenced. HMAS Moresby, under the command of Lieutenant Commander D’Arcy Gale, DSC, RAN, was the designated Headquarters Ship. In addition to Moresby, Force TOFO included HMA Ships Horsham, Benalla, Echuca, Parkes, Katoomba, Kangaroo, Bombo and the Harbour Defence Motor Launches 1322, 1324 and 1329. Dutch minesweeper Abraham Crijnssen and the transport Van den Bosch were also part of the convoy. HMA Ships Warrnambool and Gladstone also joined the convoy en route. Force TOFO arrived off Keopang Harbour, Timor, on the morning of 11 September. At around midday, Japanese representatives boarded Moresby and signed the instruments of surrender.[22]

Patrol Boat and Auxiliary Operations

The scope and pace of activities at Melville contracted following the war. However, the base continued to play an important role in defending Australia’s coastal waters and the waters of its near neighbours. HMAS Emu was a vessel that became a familiar sight in Darwin and was for a time the enduring naval presence in the area. Emu arrived in the Darwin in January 1947, where she performed a variety of duties. Emu is perhaps best remembered for rescue and salvage work, having rescued people and salvaged grounded ships in the waters off Darwin.[23]

With border protection and resource protection in mind, the Australian government decided that it needed a specialist, Australian designed and built patrol boat force. In 1967, the first of 20 Attack Class patrol boats, HMAS Attack, was commissioned into service. Five ships were based at Melville, where they bore the burden of Australia’s coastal surveillance and monitoring of the nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone in Australia’s territorial waters to the north. The Darwin patrol boat force was involved in a number of arrests of foreign fishing vessels that had been caught illegally fishing in Australian waters.[24]

On 26 September 1969, Melville was granted Freedom of Entry to the City of Darwin. While it is, of course, not unusual for Freedom of the City to be granted to a ship, this was the first instance in RAN history in which this honour was bestowed on a shore establishment.

Cyclone Tracy

In the early hours of Christmas morning 1974, Cyclone Tracy devastated the City of Darwin. Power, water and sewerage were all cut off, sadly 71 people lost their lives, and the 260 kilometre per hour winds left only 408 of the city’s 10,000 buildings intact. The Navy was not left unscathed. Naval HQ was destroyed and the oil fuel installation and communications station at Coonawarra were extensively damaged. The Naval Officer in Charge described the scene as Tracy tore through Darwin:

It is difficult to describe the hours between midnight and 0600 as the wind speed increased from some 30 knots to an estimated 170 to 180 knots...Naval Headquarters commenced disintegrating shortly after one o’clock, with the final destruction occurring at approximately 0420 when my office roof and walls collapsed inwards, burying the inmates. Subsequent refuge was taken in the cell bar behind Naval headquarters, which, although roofless, retained its walls.[25]

Three Attack Class patrol boats, HMA Ships Attack, Advance and Assail, were damaged. A fourth patrol boat, HMAS Arrow, was sunk after colliding bow first with Stokes Hill Wharf. Two crewmembers, Petty Officer Leslie Catton and Able Seaman Ian Rennie, lost their lives. Survivors of Arrow later recounted a “bloody horrifying” scene of boats and debris strewn along the harbour. Arrow was later re-floated and beached, but she was damaged beyond repair.[26]

Thirteen vessels, two Wessex helicopters from 817 and 725 Squadrons, and around 3000 RAN personnel were involved in relief efforts in Darwin. These RAN personnel were met with scenes of devastation. Commanding Officer HMAS Brisbane, Captain Michael Hudson, RAN, recounted that:

As we drove from suburb to suburb my heart sank at the enormity of the problem facing not only the Navy but all public authorities and private individuals. Although I had been listening to the various news reports while on passage, I was not prepared for the overall picture of destruction that unfolded as I drove around. I was surprised the death toll was so low.[27]

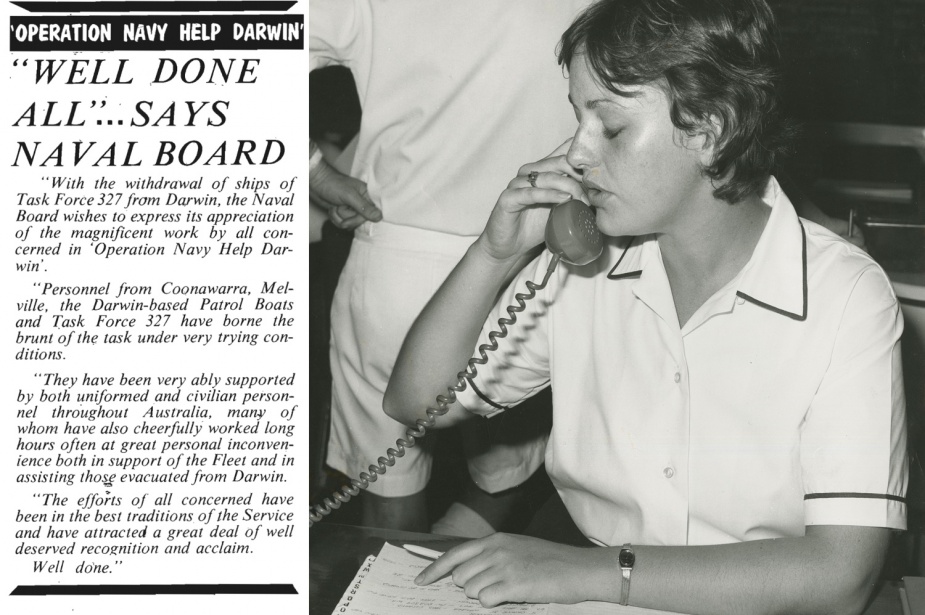

During the month long relief effort over the sweltering Top End summer, Navy personnel delivered food and medical stores, cleared more than 1590 blocks of land, installed generators, repaired electrical systems, and weatherproofed buildings. At sea, they searched for missing vessels and extracted wrecks. In total, naval personnel spent 17,979 man days ashore.[28]

Due to the damage sustained to HMAS Melville as a result of the cyclone, a decision was made to place it in abeyance on 28 December 1974 at which time all personnel were relocated and housed at HMAS Coonawarra, which had commissioned as a separate establishment on 16 March 1970. The extensive damage, coupled with plans to build new medium density housing on the land it occupied at Larrakeyah Barracks, saw Melville formally decommissioned on 21 August 1975.[29]

References

- ↑HMAS Melville - Naming, SPC-A 146AI.

- ↑HMAS Melville, SPC-A 146U.

- ↑Minute paper, Strategic Navy W/T Stations, GL Macandie, Secretary Naval Board to Secretary Department of Defence, 24 August 1936, SPC-A 146AI; Archdale Parkhill, Minister for Defence, to ET Fisk, Managing Director Amalgamated Wireless Ltd. 7 August 1936, SPC-A 146AI; Naval Bases - Australia, SPC-A.

- ↑Minute paper, Strategic Navy W/T Stations, GL Macandie, Secretary Naval Board to Secretary Department of Defence, 24 August 1936, SPC-A 146AI.

- ↑Pat Forster, ‘Fixed Naval Defences in Darwin Harbour 1939-1945’, https://seapower.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/fixed-naval-defences-darwin-harbour-1939-1945.

- ↑Naval Bases - Australia, SPC-A; Darwin Defence Co-ordination Committee, 2 September 1939, Enclosure 1, War Diary, Period 24 August 1939 to 31 May 1940, Australian War Memorial (hereafter AWM) 78 400/1.

- ↑HMAS Melville - Naming, SPC-A 146AI.

- ↑‘The Early Navy in Darwin’, The Top End Navy, p.9, SPC-A 146U.

- ↑Medical Sub-Committee to Darwin Defence Co-ordination Committee, 3 February 1940, AWM78 400/2 Part 5.

- ↑Report of Trade Defence Exercises Carried Out 26 September 1939, Enclosure 5 War Dairy, 24 August 1939 to 31 May 1940, AWM78 400/1; Report of Defence Exercise Carried Out 1 November 1939, Enclosure 11 War Dairy, 24 August 1939 to 31 May 1940, AWM78 400/1; Report of Defence Exercise Carried Out 1 November 1939, Local Defence Exercises, 13-16 May 1940, Enclosure 23 War Dairy, 24 August 1939 to 31 May 1940, AWM78 400/1.

- ↑David Horner, High Command: Australia’s Struggle for an Independent War Strategy, 1939-45 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1992), pp.35-8.

- ↑Darwin Defence Coordination Committee, 8 May 1940, AWM78 400/1.

- ↑War Diary, 1-30 September 1940, AWM78 400/1; War Diary P 1 January to 31 March 1942, AWM78 400/2 Part 4; Forster, ‘Fixed Naval Defences in Darwin Harbour 1939-1945’.

- ↑War Diary, 1 October-31 December, 1941, AWM78 400/2 Part 5.

- ↑‘Evacuation Order’, 16 December 1941, Northern Standard (Darwin), p.1.

- ↑War Diary, 1 October-31 December 1941, AWM78 100/2 Part 5.

- ↑Robert A Hall, The Black Diggers (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1997), p.100.

- ↑War Diary, 1 October to 31 December 1941, AWM78 100/2 Part 5; Diana Millar, ‘The Bombing of Darwin’, Agora, Vol. 49, No. 2 (2014): pp.33-38.

- ↑War Diary, 1 January to 31 March 1942, AWM78 400/2 Part 4.

- ↑Report on Sinking of HMAS Patricia Cam by Enemy Action on 22 January, 1943, Lieutenant Meldrum to Naval Officer in Charge, Darwin, Ship History: HMAS Patricia Cam, SPC-A.

- ↑HV Evatt, ‘Risks of a Big-Power Peace’, Foreign Affairs Vol. 24, No. 2 (1946): pp.195-209.

- ↑War Diary, 1 July to 30 September 1945, AWM78 400/2 Part 1.

- ↑HMAS Emu, https://seapower.navy.gov.au/hmas-emu.

- ↑‘Patrol Boat Operations’, The Top End Navy, pp.37-8, SPC-A 146U.

- ↑North Australia Area Report of Proceedings for Period Ended 31 December 1974, AWM78 403/5.

- ↑‘Operation Navy Help Darwin’, 17 January 1975, Navy News, Vol. 18, No. 1, p.1; HMAS Arrow, https://seapower.navy.gov.au/hmas-arrow.

- ↑Reports of Proceedings January 1975, HMAS Brisbane, AWM78 70/8 Part 2.

- ↑Brett Mitchell, ‘Disaster Relief - Cyclone Tracy and Tasman Bridge’, Sea Power Centre - Australia https://seapower.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/disaster-relief-cyclone-tracy-and-tasman-bridge; ‘RAN Launches Its Greatest Peacetime Operation ‘Operation Navy Help Darwin’’, 17 January 1975, Navy News, Vol. 18, No. 1, p.3.

- ↑HMAS Melville, SPC-A 146U.