WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following historical account may contain images of deceased persons. Users are warned that there may be words and descriptions that may be culturally sensitive and which might not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Terms and annotations that reflect the attitude of the author or the period in which the item was written, may be considered inappropriate today.

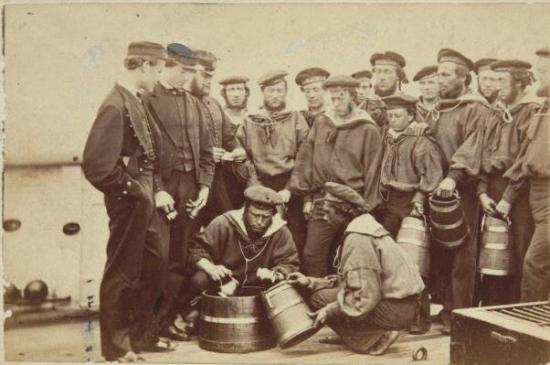

Thomas Bungalene (squatting) and other crewmembers of HMVS Victoria receiving their rum ration ca 1861. An eighth pint of rum was issued each day (State Library Victoria, H41414).

In 1861, a photograph of a young Aboriginal boy wearing Royal Naval uniform was taken among a group of sailors receiving their rum ration on board the steam sloop Her Majesty’s Victorian Ship (HMVS) Victoria. The sloop was the first colonial warship built for the Victorian colony in 1855, initially purposed for service in the Crimean War. In the annals of Australian colonial history, HMVS Victoria receives little attention, and its contribution to early maritime security is largely overlooked. As with Victoria, the service of the Aboriginal boy seen in the photograph is not well documented, when in fact he is the first known Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander naval sailor. This young Gunai Kurnai adolescent was Thomas Bungelene (also known as Bungeelene, Bungeelenee and Bungeleen). Although evidence regarding Thomas Bungalene’s life is sparse, his story is significant. As one of the first known Indigenous sailors in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), he represents an aspect of Australian history that warrants recognition. This article shares the available information about his life and service in the RAN, emphasising the importance of remembering and sharing stories about historical figures like Thomas Bungalene.

Life in the Victorian colony

Life was harsh for Aboriginal people in colonial Victoria during the 1800s. Their cultural traditions and laws were overpowered by European ethnocentric concepts that characterised them as the lowest rank in the hierarchy of races (Broome 2005). This vilification led to their population being either decimated by disease and massacres, or removed from their traditional country and placed in missions. Children were put into educational institutions to teach them how to ‘become British and Christian: the apex of human advancement’ (Broome 2005: 36). Subject to the same control from the colonial government and Christian organisations, some children were incorporated into European families.

The early colonial welfare system was based on the belief that Aboriginal children were more of a ‘threat to public order than victims of cruelty or neglect’ (Robinson 2013: 304). The treatment of Aboriginal children was underpinned by a child welfare system introduced in colonial Australia that emulated British laws regarding unruly children (Robinson 2013). The law stipulated that a ‘problem’ child could be removed from parents or guardians and placed in reform schools to be trained in manual labour, or in some cases forced to join the navy (Lewis 1965; Robinson 2013).

Thomas Bungelene and his Aboriginal family were not immune from the effects of this phase of colonisation. Thomas’s short life changed dramatically from the time of his father’s violent death at the hands of the Native Police in 1848. Thomas and his older brother Harry became wards of the Victorian government under the care of the Central Board of Aboriginal Protection (1860 to1890). During that time, it was decided that Thomas would benefit from the discipline of naval service and he was subsequently enlisted to serve in the HMVS Victoria in 1860. Under the command of Commander William Henry Norman he was taught the duties of a sailor, thus making Thomas the first Aboriginal to become a crew member of Victoria’s first colonial warship. Although Thomas was not fond of the sea-faring life, he swore to serve in Victoria (Hinkins 1884), and this proved to be an oath he did not break.

Thomas’s early life

Thomas’s life story began in 1846 when rumours of a ‘captive white woman’ in the Gippsland region circulated throughout the Australian colonies. The newspapers at the time were rife with outrageous and sometimes humorous accounts of the sightings of the fictional captive European woman appearing in different regions of Gippsland. Thomas’s father, Bungellen, who was the Aboriginal warrior leader of Gunai Kurnai people of Gippsland at that time, was blamed for the alleged kidnapping. The Colonial government took no time in directing the Victorian Native Police Corp to capture him and his wives and children, Thomas aged 6 months and his older brother Harry aged two years (Barwick and Barwick 1984; Central Board 1861).

Whilst detained at the Narree Narree Warreen Police Barracks, Bungellen was tortured by the police and died from his injuries on 22 November 1848. After Bungellen’s death, the boys and their mother were removed to the Baptist initiated Merri Merri Creek Mission Station under the orders of William Thomas, the Protector of Aborigines in Victoria (Barwick and Barwick 1984; Central Board 1861). This mission was a place where many of the Kurnai and neighbouring Woiwurrung and Boonwurrung peoples were incarcerated (Clark and Heydon 2004). Soon after their arrival at the mission their mother abandoned the boys. She later died of disease in an encampment at the junction of the Diamond Creek and the River Yarra Yarra (Central Board 1861).

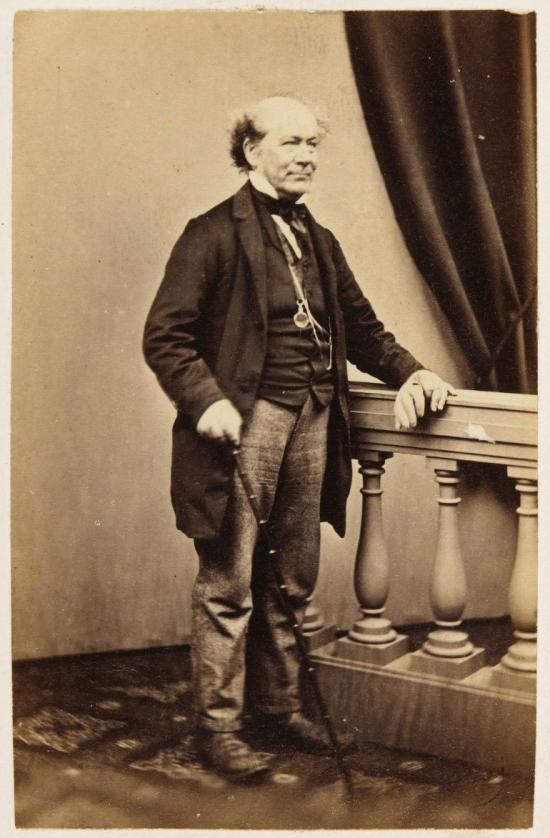

William Thomas (1793-1867) was the protector and guardian of Aborigines in Victoria from 1839 until his death. (State library Victoria H2002.87)

John Hinkins

After the mission closed in 1850, Harry and Thomas were sent to the national school at Moonee Ponds under the orders of Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe. There, under the care of school master John Hinkins, the boys learnt to read and write – skills in which they both became adept. Subsequently, Harry and Thomas became subjects of the British imperial experiment that involved teaching Aboriginal children the ‘arts of British civilisation, transforming them from hunter-gathers to a farming people, to protect them from the worst effects of colonisation’ (Broome 2005: 36). Hinkins showed great humanity towards the Aboriginal people. He had previously worked and lived with Aborigines on Gunbower sheep station on the Lower Murray, where he treated them with kindness; respecting their behaviour, customs and culture (Hinkins 1884).

John Hinkins’s concern for Harry and Thomas led him and his wife to take custody of the two orphaned boys on 31 January 1851 with the Governor’s approval. Hinkins was paid the amount of ‘five shillings per week each, and £5 for an outfit … and was to keep them until they arrived at an age capable of being apprenticed out, the expense of which, and choice of trade, to be solely confided to the Government’ (Hinkins 1884: 54).

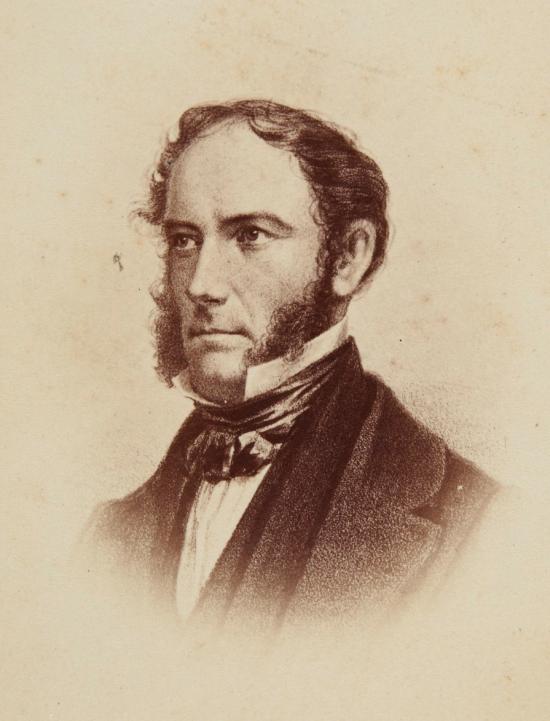

John Thomas Hinkins (1804-1883) played a great part in both John and Thomas’s lives. (State Library Victoria H5056/366)

However, life for the Hinkins family was not always smooth sailing. Hinkins described Harry as having the better disposition of the two, while Thomas was ‘pessimistic, unsociable, and bad-tempered and at times violent’ (Hinkins 1884: 55). The boys settled into family life; they became fond of going to Sunday school and church services. Both excelled in scripture and were very fond of singing hymns. Eventually Thomas’s behaviour became less troublesome and he became well-liked among the church community (Hinkins 1884).

In 1852 the boys were baptised at the Trinity Church at Pentridge by Reverend Edward Tanner, in front of the entire Moonee Ponds congregation. Hinkins renamed both the boys, calling the older boy (Harry) John, after himself, and naming Thomas after William Thomas, the Protector of Aborigines. Their Aboriginal names are unknown (Central Board 1861; Hinkins 1884:57).

Commander William Henry Norman (1812-1869) c. 1851, Commander of HMVS Victoria from 1855 until 1864 when Victoria was decommissioned. (National Library Australia, 5056548)

In late 1855, tragedy struck the Hinkins family. Thomas’s brother became seriously ill and was admitted to the government hospital in Melbourne where he died on 9 January 1856. John was buried in the Melbourne General Cemetery in the Hinkins family plot (The Argus 1856: 4). John’s death greatly affected Thomas. Hinkins noticed Thomas’s behaviour becoming increasingly erratic. This became more obvious after Hinkins took Thomas to the Theatre Royal to see his first pantomime, which Thomas enjoyed. Later, he began running away when offended, and would make his way back to Melbourne and go to the theatre (Hinkins 1884:62).

According to Hinkins, (1884:62) Thomas’s behaviour became so disruptive that he wrote a recommendation to the government to place Thomas on board the steam sloop Victoria under Captain Norman. At first, the request was denied as the Lands Commissioner preferred to keep Thomas as a messenger in the Crown Lands Office where he was employed (Central Board 1861; Hinkins 1884). However, while in this position, Thomas was reported as having associated with unsavoury characters in the streets of Melbourne after work hours and becoming incorrigible (Central Board 1862). Angered by the news of Thomas’s behaviour, Hinkins placed Thomas back in the care of the Protector of Aborigines, who put Thomas on board the Victoria (Hinkins 1884: 64).

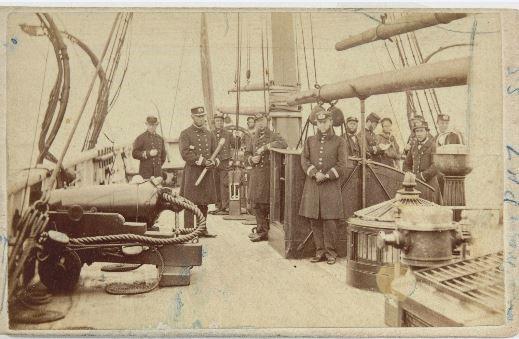

Commander William Henry Norman (holding a telescope), with other officers and crewmembers on board HMVS Victoria, c. 1851- c. 1866. Norman (1812-1869) commanded HMVS Victoria from 1855 until 1964 when it was decommissioned. Thomas Bungelene served in this ship from 1861 until 1864. (State Library Victoria, H41413)

Service in HMVS Victoria

On 5 August 1861, Thomas, aged fifteen, signed his oath as prescribed by the Regulation and Discipline of Armed Vessels Act 1860 (Vic) that he would serve Her Majesty’s peace on both land and sea for three years (Victoria Government Gazette 1860). Thomas kept this oath from 1861 to 1864. Thomas lived continuously on board the Victoria, with the exception of one or two brief visits to Melbourne and a voyage to the Gulf of Carpentaria (Central Board 1862).

During the early 19th century, the rank of boy sailor was the lowest in the shipboard hierarchy in the Royal Navy. Boys were generally the sons of sailors, or impoverished or orphaned boys, recruited to positions of personal servants to officers and trainee sailors (Pietsch 2004). The regulated age for a boy to join a ship was 13 or 11 if he was the son of a naval officer (Lewis 1965). Some children were forcibly joined up for service if they broke the law or were considered a nuisance (Lewis 1965: 155; UK Parliament 2020). Parents, guardians, parish overseers or magistrates had the option of using naval service to discipline unruly boys (Pietsch 2004). Under British Law, which was applicable at the time, authorities were allowed to remove a child from their parents or guardians and place them in industries where they were trained in manual labour (Robinson 2013). This system had negative emotional and mental impacts on the children, which led some to either behave badly or run away (Pietsch 2004). Thomas’s service was classed as disciplinary. He therefore received no wages, and his uniform and provisions were paid for by the Central Board (Central Board 1864).

Life as a sailor

There is limited documentation concerning Thomas’s life on board the Victoria. However, like many boy sailors of the time, his experiences were strictly self-contained due to periods at sea (Lavery 2018). Even when docked at ports, sailors were often confined on board – shore leave was a luxury.

For the first 12 months on board the Victoria, Captain Norman recorded Thomas’s behaviour as troublesome On one occasion, Thomas struck a petty officer and was flogged in consequence (Central Board, 1862; Central Board, 1864; Hinkins 1884:64). During the 1800s the discipline and punishment in the Navy was more severe than other armed military services. On British naval ships, punishments were considered necessary to enforce obedience and ‘to get people to do what was right for the ship’ (Lewis n.d: 45).

Flogging was common for numerous offences and acts of insubordination. Its purpose was to humiliate the offender in front of their shipmates and demonstrate that the offender submitted to authority (Lewis n.d.; UK Parliament 2020). It was not until 1860 that the issue of flogging in both the Navy and Army was debated in the UK parliament. This debate did not immediately abolish the practice, as no alternative methods were seen as necessary for maintaining order and discipline on board ship. It was not until 1876, that the issue of abolishing flogging was debated again in parliament. This led to flogging been suspended, still available as a punishment, it was used sparingly and the number of lashes were initially reduced by Parliament. Flogging was finally abolished in 1881 (Oram 2001; UK Parliament 1860; UK Parliament 1876).

Captain Norman’s main concern about Thomas was that he appeared to lack self-respect. No matter how severe the punishment, it made no impact on Thomas (Central Board 1862:14). In an attempt to deter his behaviour, Norman choose a more humane method of punishment. He made Thomas read the regulations in the Articles of War as a warning that he would be flogged if he reoffended (Hinkins 1884:64). The Articles of War were a set of regulations that served as the law as practiced on board a British Royal Navy ship (The HMS Richmond, Inc. 2002). All officers were obliged to conduct religious services in accordance with the Church of England, and all crew members were expected to maintain a high standard of morality:

All Flag Officers, and all Persons in or belonging to His Majesty's Ships or Vessels of War, being guilty of profane Oaths, Cursings, Execrations, Drunkenness, Uncleanness, or other scandalous Actions, in derogation of God's Honour, and Corruption of Good Manners, shall incur such Punishment as a Court Martial shall think fit to impose, and as the Nature and Degree of their Offence shall deserve. (The Victorian Royal Navy n.d.).

Thomas was already well-versed in the sacred and authoritative writings in religious scripture, and this knowledge did not go unnoticed. One officer observed, ‘there was no officer or man on the Victoria who had as good a knowledge of the Scripture as Thomas had’ (Hinkins 1884: 76). After reading aloud the regulations in Articles of War, Thomas appears to have come to the realisation that Captain Norman was not going to tolerate his poor conduct. Thomas did not re-offend, and later assigned to work in the engine room under the supervision of the chief engineer (Hinkins 1884: 64).

The Hinkins family still held the same affection and loyalty to Thomas during his time in the Victoria and would regularly visit Thomas after his first 12 months of service. They supported and encouraged him to overcome his temper and to submit to the orders of his officers (Hinkins 1884:64). Lieutenant Woods asserted to Hinkins that on board the Victoria he had noticed an improvement in Thomas’s behaviour and never saw him swear, lie or drink (Herald 1865:3)

The service of Victoria

Much like Thomas, Victoria was a ship of ‘firsts’. Its history started in the years preceding the outbreak of the Crimean War, at a time when the colony of Victoria was becoming world renowned for its rich alluvial goldfields (The Sydney Morning Herald 1854: 2).

Melbourne became a large and influential city where gold was being stored and exported to England and Europe by ship (Lennon 1989). Due to the fear of attack from either France or Russia, Governor La Trobe asked the colonial government to provide a warship to be stationed at the port of Melbourne (Jones 1986). While his request was denied, his successor, Captain Sir Charles Hotham KCB RN, made a successful bid for the warship. In 1854 Victoria was commissioned as an armed, sea-going screw steamer for colonial defence (Jones 1986; Knox 1972). The question of who would command the vessel was solved by a chance meeting between Hotham and Captain Norman on a voyage to Australia on Queen of the South. Impressed by Norman’s character, Hotham secured his services. Subsequently, Norman was commissioned by the colonial Victorian Government to oversee the building of the Victoria (The Argus, 1870: 7).

Sir Charles Hotham (1806-1855), naval officer, Governor of Victoria from 1854-1855. (State Library Victoria, H29538)

On 31 May 1856, four months after the end of the Crimean War, Captain Norman steamed into Port Phillip Bay (Glen 2011). Once in Australian waters, Victoria was at the disposal of the Victorian colonial police. It was commissioned for various public services from supervising the laying of submarine cables in Bass Strait to conducting rescue missions along the coastlines (Glen 2011; The Sydney Morning Herald, 1954: 11).

Victoria demonstrated its prowess as a warship in 1860. In one of a series of armed conflicts at Taranaki, New Zealand, from 1845 to 1872, Victoria was assigned to the British military. It was commissioned as a troop and munitions carrier to transport two companies of the 12th and 40th Regiments from Tasmania to Nelson, New Zealand (Greig 1923; Jones 1986; Nicholls 1988). Victoria also carried out shore bombardments and coastal patrols while maintaining supply routes between Auckland and New Plymouth (Nicholls 1988). On one occasion, when the Maoris were about to attack New Plymouth, all the women and children of that township were boarded onto Victoria and taken to Nelson for safety (Greig 1923: 104).

Captain Norman, his officers and crew were deployed for 12 months during the Taranaki campaign. Their commendable conduct was noted by both the House of Parliament and Major General Pratt, Commander-in-Chief of the British military forces (The Argus 1870: 7). However, as Victoria was deployed outside of colonial waters its contribution was not officially acknowledged by the British Crown, as it was not commanded by a Crown commissioned officer or officially recognised as part of the Royal Navy (Lewis 1965). Victoria did, however, attract favourable comments and attention. General Sir Charles William Pasley KCB FRS recorded his observations of Victoria’s service:

Her Majesty’s ships do not give us much assistance at sea as I think they might, and I do not know how we should get on if it were not for the Steam Sloop of War Victoria which is the property of the Government of Victoria and has been lent by them to the General … she does ten times more work at sea than all the rest of the Squadron (consisting of four large steamers and a Frigate) put together… (Captain Charles Pasley, September 6 cir.1860 cited in SPC - A n.d.).

The search for Burke and Wills

Victoria’s commendable service was to continue following its return from the Taranaki campaign in 1861. Barely had it returned to Port Phillip when, on 10 April 1861, news reached Melbourne that fears were held for the Burke and Wills exploration party that was heading north across the continent towards the Gulf of Carpentaria (The Argus 1870: 7). Norman was commissioned as the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Expedition Parties, a humanitarian mission to the Gulf to render relief to the missing party (Landsborough 1862; Norman 1862). On 4 August 1861, Norman with his crew, including Boy 2nd Class Thomas Bungelene, sailed in Victoria from Melbourne to meet with other ships conveying stores to the Gulf (Norman 1862; SPC-A, n.d). In spite of the relief effort, Burke and Wills did not survive (Landsborough 1862:130).

Captain Norman and his crew were commended for their resourcefulness and ability in carrying out their duties in the face of difficulties during the deployment to the Gulf (Greig 1923; The Argus 1862: 5). The voyage itself was to prove challenging in the face of inclement weather when Victoria and the brig Firefly, also chartered to convey the relief party and equipment, encountered strong winds between Brisbane and the Great Barrier Reef. Victoria lost sight of Firefly, which had broadsided on a reef north of Sir Charles Hardy Islands (Landsborough 1862). A few hours later, Victoria reunited with Firefly and its stranded crew and cargo. Norman, with his first lieutenant and 24 crew, worked to lighten its load to keep the wreck afloat while carrying out repairs on its hull. Victoria reloaded Firefly’s cargo, surviving horses, stores and crew and continued the passage north on 22 September, with Firefly in tow (Norman 1862).

For the rest of the mission, Norman and his crew spent most of their time ashore waiting for the expedition search parties to return to the ships, where they found the ‘heat, mosquitoes and sand-flies were too much for sleep’ (Norman 1862). After hearing of the news of the demise of Burke and Wills, Victoria returned from the Gulf, anchoring in Hobson’s Bay on 31 March 1862 (Norman 1862). On the main deck, Captain Norman and his crew, including Thomas Bungelene, were presented certificates from the Exploration Committee of the Royal Society in recognition of their admirable conduct and skill demonstrated during the expedition (The Argus 1862:5). Hinkins kept Thomas’s certificate hanging on his living room wall, a copy of which can be seen in Hinkins’s biography Life Amongst the Natives.

Discharge from naval service and premature death

At the end of August 1864, Victoria’s crew was paid off and the ship was passed to survey services under the command of Captain Cox (Jones 1986). After the crew’s demobilisation, Thomas was discharged and returned home to the Hinkins family where he was unemployed for a short period, prior to his placement in the Minister of Mines office. There he thrived in his new employment until on 3 January 1865, when he contracted typhoid and died at home with Hinkins sitting vigil at his deathbed (Hinkins 1884). Thomas was barely eighteen years of age.

The passing of Thomas went largely unnoticed by the Central Board which seemed more intent on dismissing his short life as a failed social experiment. To the board it was a lost opportunity to prove to the British Empire that Aborigines of Australia could be educated to become good citizens (Central Board 1861:8). The board’s last entry in their fifth report on Thomas read:

A hope was entertained at one time that [Thomas] would become a useful member of society; but whether owing to defects in his early education or a natural propensity to evil, he became nearly as troublesome in the office as he was when on board the Victoria (Central Board 1864: 18).

The board’s fundamental aim was to educate the Aboriginal child with the Christian concept of civilising the primitive savage, and guide them to the European way of life (Burridge and Chodiewicz 2012).

There were others who held opposing views of Thomas’s conduct and ability. During his time in the office of the minister of mines, Thomas was regarded as a skilled copywriter and technical draftsperson, skills he had acquired while serving in the Victoria (Hinkins 1884). Just two weeks prior to his death, he had gained membership into the Independent Order of the Oddfellow’s Loyal Albert Lodge, Manchester Unity (Central Board 1864: 12; Hinkins 1884), an organisation that had strict entry requirements – members had to be of sound health and pass means, religious and moral tests (Museum Victoria Collections 2020). Thomas was highly regarded in the Moonee Ponds community who remembered him as having a passion for singing and recitations and on occasion would, ‘take a great delight in attending the Temperance Meetings held in the district, and many were the enjoyable evenings spent by those attending to hear the songs and recitations given by him, a number of which he learned while on board the Victoria’ (Herald 1865:3; Hinkins 1884:77).

Hinkins (1884) reminisced that Thomas’s funeral on 5 January was attended by many community members, including those from the Oddfellow’s Lodge and St Thomas’ Sunday school which Thomas and his older brother John had attended as children. The children from the school wore white scarves and hatbands in memory and respect for Thomas. He was laid to rest in the same grave as his older brother John. Later, a headstone was erected with the money raised by the children and teachers of St Thomas’ Sunday school (Punkle 1866 cited in Hinkins 1884:74)

Final service of Victoria

Decommissioned prior to Thomas’s death, Victoria, no longer the modern warship once regaled as the foundation of the naval power in the southern seas, and its previous services were soon forgotten. By 1866, Victoria was refitted as a marine survey vessel under the command of Captain H J Stanley, and later, Chief Officer Lieutenant George Philip Tandy (Nicholls 1988). For the next decade, Victoria was employed on non-naval jobs for the Victorian Government, mostly as a survey ship along the coastline replacing and servicing buoys and beacons, and transporting stores and materials to various lighthouses and coastal telegraph stations (Queensland Times 1866: 4; Nicholls 1988; The Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil 1874: 55; The Sydney Morning Herald, 1954: 11).

By 1876, Victoria exhibited considerable neglect. Under the command of Lieutenant Tandy, Victoria ran aground twice. This led to his dismissal in 1876 (The Age 1876: 3; Nicolls 1988). Victoria sustained further damage in 1880 during a despatch to Cape Otway to retrieve survivors from the wreck of the American ship, Eric the Red (The Sydney Morning Herald 1954). By 1882, Victoria’s service was finished. Victoria was purchased in 1894 by William Marr, a shipwright from Williamstown (Davis 1992: Gillett 1982; Greig 1919, 1923). After three years, its gunmetal flanges, pure copper keel sheets and the mahogany ship’s wheel, emblazoned with the coat-of-arms of the kangaroo and emu, were removed or melted down (Greig 1923). The only recorded relics that are known to survive are a binnacle case and ‘magazine for boat service’ that were donated from a private collector to the Society of Victoria in 1911 (Greig 1919). In 1919, the relics were offered to the trustees of the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne, where they were placed in its museum (Greig 1919). According to Greig (1923) the salvage of these remaining relics closed the records of Victoria as one of the first Australian warships.

Conclusion

Thomas Bungelene and HMVS Victoria have become entwined, as both represent ‘firsts’ in a unique chapter of Australian maritime history. Until recently, Thomas had barely been mentioned in the historical records as the first Aboriginal sailor. His short life was mostly documented in the reports of the Central Board, as an object of curiosity. Mention of his life on board Victoria, is confined mainly to episodes of lapses in discipline. However, in his guardian’s diary, Hinkins provided an insightful view of Thomas’s character and life, how he navigated through the complexities of Christianity and the European way of life.

In its glory, Victoria was regaled by a prestigious newspaper when it left Limehouse dockyard as the prototype for a new naval power in the southern seas. However, Victoria’s

Life as a naval warship was disrupted from the outset when it entered Australian waters. Its only warfare service was participating in the Taranaki campaign. As Victoria was not a commissioned Royal Navy warship, this service went largely unrecognised by the British Crown. However, one British officer observed that the hardy steam sloop was a credit to the Victorian Colonial Government and could out manoeuvre many of the British naval steamers and frigates. Victoria’s civil services to the Victorian colony were of enormous value, notably services rendered during the Burke and Wills rescue mission.

Although there is little historical evidence of the association between Thomas and Victoria, we are reminded of his service by the photograph taken in 1861 that appears at the beginning of this paper – that of a young uniform-clad Aboriginal boy sailor, dutifully assisting in serving a rum ration to his fellow shipmates. This poignant snapshot in time records the service of Boy 2nd Class Thomas Bungelene, the first Aboriginal colonial sailor on board the first colonial warship HMVS Victoria. In 2007, the Governor-General of Australia approved the Campaign Award, NEW ZEALAND 1860-61, in recognition of Victoria’s participation in the New Zealand campaign. In doing so it became the first battle honour carried by the Royal Australian Navy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to the members of the historical Sea Power Centre - Australia for their valuable guidance, encourage and wonderful support throughout the process of writing and publishing my paper. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC) for their support and permission to publish this important story and history behind Thomas Bungalene.

To Sea Power Centre – Australia - This is for you!

References

Barwick, R.E., Barwick D. E., 1984. A Memorial for Thomas Bungeleen, 1847-1865. Aboriginal History, 8(1/2):8-11.

Broome, R., 2005. Aboriginal Victorians: a history since 1800. Allen & Unwin. Crow’s Nest, N.S.W.

Burridge, N., and Chodkiewicz, A. 2012. A Historical Overview of Aboriginal education Policies in the Australian Context. In Burridge, N., Whalan, F., and Vaughan, K. (Eds.). 2012. Indigenous Education: A Learning Journey for Teachers, Schools and Communities. Sense Publishers: Rotterdam. (Pp. 11-22).

Central Board, 1861. First report of the Central Board Appointed to Watch over the Interests of the Aborigines in the Colony of Victoria: Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by his Excellency’s Command. John Ferres, Govt. Printer, Melbourne.

Central Board, 1862. Secondreport of the Central Board Appointed to Watch over the Interests of the Aborigines in the Colony of Victoria: Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by his Excellency’s Command John Ferres, Govt. Printer, Melbourne.

Central Board, 1864. Fourth report of the Central Board Appointed to Watch over the Interests of the Aborigines in the Colony of Victoria: Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by his Excellency’s Command John Ferres, Govt. Printer, Melbourne.

Clark, I. D., and Heydon, T., 2004. A Bend in the Yarra: A History of the Merri Creek Protectorate Station and Merri Creek Aboriginal School 1841-1851. Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra.

Davis, D, F., 1992. Australia’s First Warship. HM Victorian Ship VICTORIA. Naval Historical Review, 13(4): 26-27.

Gillett, R., 1982. Australia’s Colonial Navies. The Naval Historical Society of Australia: Garden Island, NSW.

Glen, F. 2011. Australians at War in New Zealand. Willsonscott Publishing International Limited: Christchurch, New Zealand.

Greig, A. W. 1919. Our First Warship. The Argus, Saturday May 3 1919:6.

Greig, A.W. 1923. The First Australian Warship. Victorian Historical Magazine, Vol 9, Issue 36:97-114.

Herald, 1865. Death of an Educated Aboriginal Native. Herald, Thursday 5 January 1865:3.

Hinkins, J. T., 1884. Life amongst the Native Race: With Extracts from a Diary by the Late John T. Hinkins. W.T. Quinton, Flemington.

Illustrated London News Ltd., 1855. Launch of the War-Steamer “Victoria”. Illustrated London News Ltd, Saturday, July 7, Vol 7, Issue 751, 1855:5.

Jones, C., 1986. Australian Colonial Navies. Australian War Memorial: Canberra.

Knox B. A., 1972. Hotham, Sir Charles (1806–1855), Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University: Canberra. Retrieved from: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hotham-sir-charles-3803/text6027.

Landsborough, W., 1862. Journal of Landsborough's Expedition from Carpentaria, in Search of Burke & Wills. F.F. Bailliere: Melbourne. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52796205.

Lavery, B., 2018. Shipboard Life and Organisation 1731-1815. Routledge; New York.

Lennon, J. 1989. Interpreting Victoria's gold rushes. Historic Environment, Vol 7, No. 1: 21-29

Lewis, M., 1965. The Navy in Transition: A Social History 1814-1864. Hodder and Stoughton Ltd: London.

Lewis, T., n.d. Readings in Naval History, Royal Australian Naval College: Jervis Bay, Australia.

Museum Victoria Collection, 2020. Independent Order of Oddfellows. Retrieved from https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/2783.

Nicholls, B., 1988. The Colonial Volunteers: The Defence Forces of the Australian Colonies 1836-1901. Allen and Unwin: Sydney.

Norman, W.H., 1862. Exploration expedition: report of Commander Norman, of H.M.C.S "Victoria”: together with copy of his journal on the late expedition to the Gulf of Carpentaria. No. 190. Melbourne. Retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-134071348.

Oram, G. 2001. The Administration of discipline by the English is very rigid: British Military Law and Death Penalty (1868 -1918). Crime, History & Societies. Vol 5(1)93-110. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4000/chs.782

Pietsch, R., 2004. Ships’ Boys and Youth Culture in Eighteenth Century Britain: The Navy Recruits of the London Marine Society. The Northern Mariner/Le Marin du Nord, Vol 15, No. 4:11-24.

Queensland Times, 1866. H.M.C.S. Victoria. Queensland Times, Thursday 9 August 1866:4.

Robinson, S., 2013. Regulating the Race: Aboriginal Children in Private European Homes in Colonial Australia. Journal of Australian Studies, V 37, No. 3:302-315.

Victoria Government Gazette, ‘An Act to provide for the better regulation and discipline of Armed Vessels in the service of Her Majesty's Local Government in Victoria.’ 8 June 1860, https://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-in/viewdb//au/legis/vic/hist_act/aatpft….

The Age, 1876. The Dismissal of Lieutenant Tandy. The Age, Friday 21 January 1876:3.

The Argus, 1856. Death Notice. The Argus, Thursday 10 January, 1856:4.

The Argus, 1862. Presentation to Capt. Norman of the Victoria. The Argus, Thursday 19 June, 1862:5.

The Argus, 1870. The Late Captain Norman. The Argus, Saturday 22 January 1870:7.

The Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 1874. Our Victorian Navy. The Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, Saturday, 11 July 1874:55.

The HMS Richmond, Inc., 2004. Royal Navy: Article of War. Retrieved from https://www.hmsrichmond.org/sitemap.htm.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 1854. Council Paper. The Sydney Morning Herald, Tuesday 28 March, 1854:2.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 1954. Special Feature: Our Navy is 100 Years Old. The Sydney Morning Herald, Friday 22 October, 1954:11.

The Victorian Royal Navy, ‘An Act for amending, explaining and reducing into one Act of Parliament, the Laws relating to the Government of His Majesty's Ships, Vessels and Forces by Sea.’ II, 2, https://www.pdavis.nl/NDA1749.htm.

UK Parliament, 2020. Navy – Punishment of Flogging. Volume 230: debated on Tuesday 20 June 1876. Retrieved from https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1876-06-20/debates/b6898477-ad45-…—PunishmentOfFlogging.

UK Parliament, 2025. Flogging (Army and Navy). Volume 156: debated on Thursday 16 February 1860. Retrieved from Flogging (Army and Navy) - Hansard - UK Parliament.