The service history and fate of HMAS Perth (I) are widely known. However, one part of Perth’s story remains largely untold. That is, how Perth’s two bells came back to Australia after the ship was wrecked in the Second World War.

I am a scholar of maritime heritage in Southeast Asia, with a particular interest in the ethics and politics of shipwrecks. My current research focuses on sunken warships in Southeast Asia.

I learnt about the industrial salvage of Perth in Banten Bay while researching a 9th century wreck in Indonesia. I had worked as a graduate at Defence, including on the Indonesia and Timor-Leste desks in the International Policy Division. For that reason, the news piqued my interest. Once I completed my PhD, I focused on uncovering Perth's story.

In this article, I trace the history of the bells, from 1 March 1942—when Perth sank under enemy fire—to the present day.

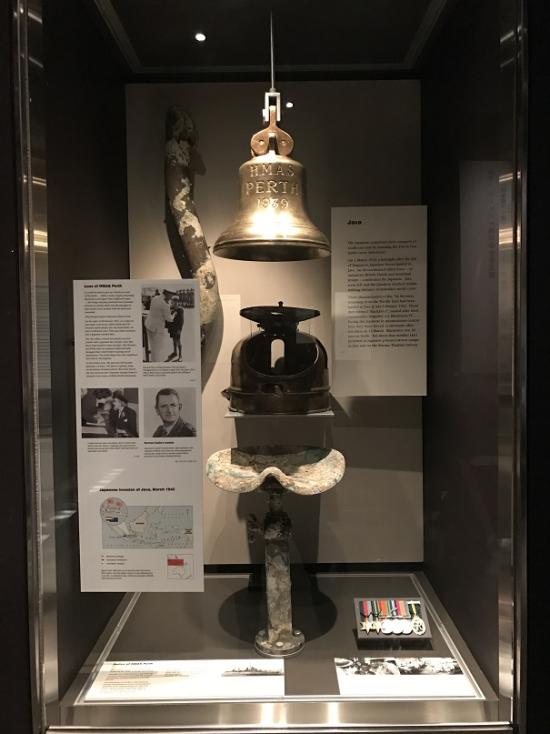

The Perth display at the Australian War Memorial

The bells today

Perth’s working bell is on display at the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra. The exhibit tells Perth’s story to over a million visitors each year.

A memorial in east Fremantle speaks to the significance of this ship and its successors, HMAS Perth (II) and (III).

Perth’s ceremonial bell is displayed in the foyer of the City of Perth Town Hall. The bell hangs low enough that visitors can touch it.

In Indonesia, annual ceremonies are held in Banten Bay. These bring together representatives from Australia, the United States and Indonesia. Visitors pay tribute by throwing wreaths on the water above the wrecks of Perth and USS Houston.

In the gardens of the Australian Embassy in Jakarta, frangipani flowers fall onto a plaque commemorating the two ships. Frangipani trees are common in Indonesian cemeteries.

The HMAS Perth (I) Memorial at East Fremantle, opened 1 March 2025. Source: HMAS Perth (I) Memorial, 2025.

Early efforts to retrieve the bells

The lack of information on the post-sinking histories of Perth's bells does not mean a lack of interest. David Burchell’s 1971 book The Bells of Sunda Strait takes its title from his attempts to recover the bells. In a letter to the director of the AWM in 1967, Burchell said he wanted to give the bells to the museum in 'commemoration to the men who died during this battle which was one of the most courageous in Australian naval history.'

Burchell located the wreck in May 1967, but did not find the bell. He believed the bell was in the quartermaster’s lobby. The ship was lying on its port side, which made it difficult to find the right door. Burchell recounted in The Bells of Sunda Strait that when he found the entrance, he could not open it.

The Sun newspaper reported in 1967 that Burchell thought 'if the bell is still with the Perth, it’s probably well below the mud and sand'. Or, as Burchell said in his 1978 article, ‘Recovery of Ship’s Bell HMAS Perth’ (download the article in PDF), it 'had been blown off its mounts during the ship’s last action'.

Burchell recovered around 24 other objects from the wreck, including:

- the binnacle from the bridge

- a 20-inch search light

- a brass seat from the compass platform

- a gyro-repeater from the wheelhouse

- a porthole from the vicinity of the quarterdeck

- a voice tube.

Most were given to the AWM on 11 November 1967 at a ceremony attended by Burchell, Indonesian Navy liaison officer Captain Sumantri, the Indonesian and American ambassadors to Australia, and around 100 members of the ex-HMAS Perth Association.

Burchell had not realised that Perth was carrying two bells when it sank. A working bell for daily use above deck and a ceremonial bell that was probably below deck. The ceremonial bell was embellished with two circles of oak leaves on the top and bottom edges. Each bell bore the engraving ‘HMS Amphion 1935’. On transfer to the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), ‘HMAS Perth 1939’ was engraved on the reverse side.

The working bell

Burchell recounted that in mid-1974, he heard from Captain Sumantri that a bell from Perth had turned up in an Indonesian salvage yard. As reported in The Sunday Mail in 1974, Burchell flew to Jakarta to meet the head of the salvage firm, former Indonesian military officer Major General Soehardi.

According to a 1974 cablegram, Soehardi was unwilling to release the bell without payment. Burchell argued Australia had already paid for the bell 'with the lives of 353 men that went down with the ship and another 100 who died in POW camps' (The Sunday Mail, 1974).

A 1976 memo to the AWM’s director shows that Burchell sought help from the Australian Embassy in Jakarta in August 1974. The embassy knew the bell was not the Indonesian salvage company’s to sell. However, they also recognised that arguing about the legalities of ownership would not get the bell back.

Prioritising the bell's return, the embassy gave the salvage company a Hercules class 17-foot aluminium diving boat worth about A$3000, (approximately $30 000 today). In exchange, the bell was handed over to the embassy in a small ceremony on 21 November 1974.

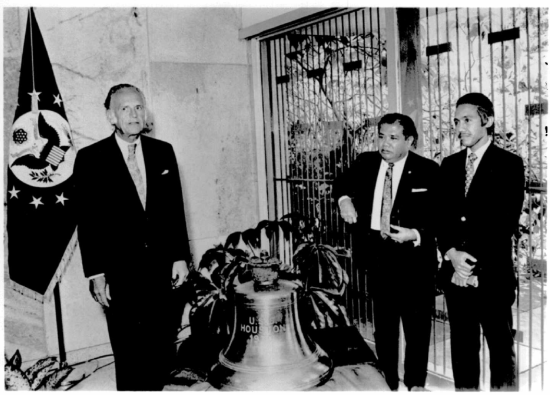

Soehardi hands the USS Houston bell over to Francis Galbraith, the American Ambassador to Indonesia, 24 August 1973. Source: Pamphlet, 'USS Houston Ceremony [Ship’s bell], Jakarta, Indonesia, August 24, 1973', held by University of Houston Libraries Special Collections Box 19 Folder 21.

There was a precedent for this exchange. In The Ghost that Died at Sunda Strait, Walter Winslow said Soehardi presented the American ambassador to Indonesia with a bell from Houston, which had been salvaged in July 1973. In return, the Americans gave the salvage firm surplus diving gear.

On 26 November 1974, Perth’s working bell was flown to Canberra. There it underwent months of conservation at the AWM. In 1976, the bell featured in an episode of This is Your Life dedicated to Burchell’s life and work.

Today, the bell is displayed in the Second World War Singapore gallery with other objects Burchell recovered.

The ceremonial bell

The ceremonial bell’s location remained unknown until the mid-1980s. In January 1985, a diver offered the RAN a bell they recovered from Perth’s wreck in exchange for $10 000. According to the diver, the bell had been mounted on the gallows by Y turret.

The RAN passed the offer to the AWM. Gavin Fry, acting assistant director programmes and collections, expressed three main concerns in a 1985 letter:

- the asking price was 'by far and away too much for a relic of this type'

- the AWM already had Perth’s 'primary bell'

- there were questions about the legality of the diver even owning the bell.

Fry responded to the RAN in a file note:

The most important issue to address, it is suggested, is whether the man who acquired it sought permission from the Department of Defence to dive on the wreck. The HMAS Perth is not a proclaimed war grave, but it is understood, however, to still be the property of the Australian Government. In these circumstances a diver would be required to seek permission to dive on the wreck and should he remove items without seeking approval the matter could perhaps be treated as theft.

Despite its concerns, the AWM did not rule out the possibility of accepting the bell as a gift.

But a buyer was found: the state of Western Australia. According to the Western Australian Museum’s records, former state premier Brian Burke and local real estate agent Chas Clifford helped secure the bell.

City of Perth Town Hall’s records also show the involvement of Australian businessman Warren Anderson and then-Perth Lord Mayor Michael Agapitos Michaels. Anderson and Michaels raised the funds to acquire the bell.

As Michaels noted in a 2012 letter:

The bell of course came from a War Grave and as such should not have been disturbed but when I was approached the bell was on land and offered for sale and it seemed to me that the final home for the bell should be its namesake city where its significance would be appreciated.

The City of Perth acquired the bell in the mid-1980s. Michaels presented it at a 1986 ceremony attended by Perth survivors. In 2010 the bell underwent six months of restoration at the Western Australian Museum. It was then returned to the foyer of the Perth Town Hall, where it remains today.

HMAS Perth’s ceremonial bell following restoration in 2010. Image: Western Australian Museum.

From the depths to on display

In both instances, the working bell and the ceremonial bell simply turned up. There was no detail about how they were removed from the wreck. It was not until 2012 that it was confirmed that Burchell had not been the only one searching for the bells.

In August 2012, marine salvager David Barnett donated three dinner and nine side plates recovered from Perth’s wreck to the Western Australian Maritime Museum. These were later acquired by RAN’s Naval Heritage Collection.

The plates had been recovered from Perth in the late 1960s and 1970s, when Barnett worked as a subcontractor to an Indonesian marine salvage firm. Barnett, operating from his salvage ship Radar, was contracted on a 21 per cent commission, while local divers were paid US$1 per day.

The salvage firm, PT Antasena, operated under an Indonesian government permit. Barnett thought he was operating within a legal framework endorsed by the Indonesian government. The principal of this salvage firm was Major General Soehardi—the same Soehardi with whom David Burchell had negotiated over Perth’s working bell in 1974.

Barnett’s account revealed decades of systematic, profit-driven salvaging of the wreck. Barnett said:

By the time [I] got there the propellers were gone and work was well underway… the chief diver Harry had already got one bell from the Perth recovered from the bridge; this was the working bell that eventually made its way to the Australian War Memorial.

Barnett dived the site, in his words, 'probably a dozen times'.

Unlike Burchell, Barnett seemed to be aware there were two bells on board. Like Burchell, he wanted to ensure that both bells were returned to Australia rather than being sold to other bidders. The Sunday Mail reported in 1974 that two Japanese millionaires were interested in acquiring the bell. With that in mind, Barnett told the divers: 'If you find the Quarterdeck bell at X turret I will give you 10 million Rupiah.'

Thus motivated, the divers gave the ceremonial bell to Barnett. Barnett paid the divers with the money that had been committed by the Western Australians.

To avoid Soehardi’s intervention, Barnett arranged for the bell to be taken by sea to Singapore. From there, Qantas flew it to Perth, free of charge.

Burchell’s salvaging was motivated by a desire to commemorate and repatriate. In contrast, the salvaging that led to the recovery of Perth’s and Houston’s bells was profit-driven. Perth’s working bell was exchanged for a $3000 boat. The ceremonial bell was sold to the City of Perth. Houston’s bell was exchanged for costly diving equipment. These symbolic objects were all recovered for profit.

In 2017, a joint-Australian Indonesian survey found that less than 40 per cent of Perth remained in situ due to salvaging. We are lucky that the actions of both Burchell and Barnett, coupled with the involvement of diplomats and businesspeople, ensured the return of Perth’s bells.

To hear a range of perspectives on HMAS Perth (I), please visit the limited podcast series, Perth’s Stories: A Shared History: https://soundcloud.com/hmasperthi_asharedhistory. Transcripts are available through each episode’s page in English and Indonesian.

Acknowledgments

Dr Natali Pearson is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Award (DE250100827: Sunken Warships: Heritage Diplomacy in Maritime Southeast Asia) funded by the Australian Government.

A version of this article was originally presented at the 2017 Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage, Hong Kong SAR.

The Perth’s Stories podcast was supported by a Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Maritime Capacity Building Initiative grant to the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Thank you to staff at the Royal Australian Navy’s Sea Power Centre, the Western Australian Shipwrecks Museum, the Australian War Memorial and Perth Heritage for their assistance.

References

Anonymous. (1973). [Pamphlet with speeches and photos] USS Houston Ceremony [Ship’s bell], Jakarta, Indonesia, August 24, 1973 24 August 1973. https://findingaids.lib.uh.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/374586, Texas, Houston, University of Houston Libraries Special Collections, Box: 19, Folder: 21. Cruiser Houston Collection, 1981-001

Anonymous. (1974). Salvage of WWII HMAS Perth: Inward cablegram (6 September 1974). Jakarta: Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs.

Burchell, D. (1967). [Letter] Letter to Director, Australian War Memorial 3 July 1967.

Burchell, D. (1971). The Bells of Sunda Strait. Adelaide, Rigby.

Burchell, D. (1978). Recovery of Ship's Bell, HMAS Perth. Journal of the Australian Naval Institute, 4(4), 56-58.

Burness, P. (1975). [Memo] Memo to the Director, AWM, 17 March 1975, Re. Ship's Bell - HMAS PERTH 1975.

Burness, P. (1976). [Memo] Memo from Curator Relics to the Director AWM, regarding correspondence HMAS Perth's bell, 4 February 1976.

Carpenter, J. (2010). HMAS Perth I Ceremonial Bell Conservation Treatment Perth: Western Australian Museum.

Francis, B. (1974, Date unknown: probably September or October). War ship's bell on way home, thanks to Adelaide skin diver. Sunday Mail.

Fry, G. (1985a). Letter to Director Australian War Memorial, regarding Bell from HMAS Perth (30 January 1985). Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

Fry, G. (1985b). Note for file: HMAS Perth Bell (1 February 1985). Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

Hosty, K., Hunter, J., & Adhityatama, S. (2018). Death by a Thousand Cuts: An archaeological assessment of souveniring and salvage on the Australian cruiser HMAS Perth (I). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 47(2), 281-299.

McCarthy, M. (2012). HMAS Perth plates: Brief prepared for Andrew Viduka, 14 August Fremantle: WA Maritime Museum.

Michael, D. (2012a). [Personal communication via email] HMAS Perth Heritage Items: Return to Navy [SEC=UNCLASSIFIED] 16 August 2012a.

Michael, D. (2012b). [Personal communication via email] HMAS Perth I: Draft Letter: Mr D Barnett [SEC=UNCLASSIFIED] 2 September 2012b.

Offen, R. (2017). [Personal communication via email] RE: Website feedback from Heritage Perth website 12 July 2017.

Pearson, N. (2017). Naval Shipwrecks in Indonesia. Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage, Hong Kong SAR. https://www.academia.edu/33914782/Naval_shipwrecks_in_Indonesia

Perryman, T. (2000). [Letter] HMAS Perth's Bell 14 January 2000.

The Sun Newspaper. (1967, 27 June). The Man Who Found the Perth. The Sun, 26-27.

Wallace, K. (2007). Sunda Strait – The Last Day of Summer. Self-published.

Winslow, W. G. (1984). The Ghost that Died at Sunda Strait. Annapolis, Naval Institute Press.